One of the most iconic moments of the 20th century was the first step by a human on the surface of another planetary body. That first footprint was, of course, made by Neil Armstrong on the moon on July 21, 1969. Like many of you, I was not alive to witness this historic event, and so have spent much of my career dreaming of the time when humans will once again venture beyond the protection of low Earth orbit, back to the moon, and then on to Mars. That day is getting tantalizingly close with the launch of NASA’s Artemis Program.

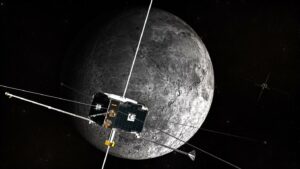

Canada was one of the first countries to join NASA in this next international endeavour, building on the success of our contributions to the International Space Station. In one of the most exciting announcements for the Canadian space program in recent memory, the Canadian Space Agency announced that a Canadian astronaut will fly on the Artemis 2 mission. This first crewed mission of NASA’s Artemis program will see humans fly to the moon and back for the first time since 1972 in preparation for the Artemis 3 mission, which will land on the lunar surface.

One of the major goals of returning to the moon is to answer new questions about the origin and evolution of our closest neighbour, and also discover what it can tell us about the early history of Earth and even the origin of life. The moon, unlike the Earth, has locked up in its rocks a record of the first billion years of the solar system’s history.

With this impending requirement to do geology on the lunar surface in mind, I recently took Canadian astronaut Joshua Kutryk and NASA Artemis astronaut Matthew Dominick with me on an expedition to the Kamestastin (or Mistastin) Lake meteorite impact structure in northern Labrador. Both Joshua and Matthew are pilots by training – like most of the Apollo astronauts – and so this expedition was an opportunity for them to build on the introductory geology training that they gained during their two years as astronaut candidates. But more than this, meteorite impact craters are the dominant geological feature on the moon – there are literally hundreds of thousands of them – and so every Artemis mission will entail exploring impact craters in one way or another.