Exploration

Canadian Space Agency astronaut profiles

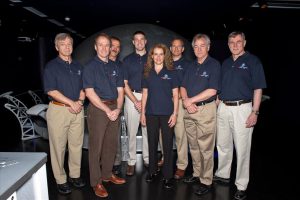

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

- 1067 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Learning to survive the Russian wilderness in winter with the most basic of survival kits and diving almost 20 metres into an underwater lab to spend days in cramped quarters with your colleagues are just a few of the challenges of being an astronaut. Everything you do, every mistake you make, is evaluated even as you push yourself physically and emotionally. Is it enough to make it into space? You’ll only know when you get the assignment.

The first rule of being an astronaut is realizing how much you don’t know, and how much you’ll never know.

Canadian astronauts David Saint-Jacques and Jeremy Hansen are more than five years into preparing for an eventual mission to the International Space Station. “You’ll never be an expert in those systems,” says Hansen — although the astronauts certainly do their best. Training for the space station ranges from learning how to use its toilet and exercise bike and preparing rehydrated food, to operating complex experiments and performing maintenance in and outside the station.

The more well-known repairs take place on the station’s exterior. Then there’s the risk of spacewalking astronauts being hit by meteors, or of floating away (which the Canadian Space Agency and NASA mitigate by requiring that astronauts use tethers). It’s physically demanding and psychologically taxing, requiring that astronauts are practiced in pacing themselves while completing delicate tasks.

For years before they do any of this, astronauts work to learn things such as how to exercise, how to eat and even how to speak other languages.

Hansen and Saint-Jacques joined a group of other astronauts from around the world, all selected in 2009, for a two-year basic training course that NASA calls “astronaut candidate” training. Candidates learn the ins and outs of the ISS and also begin honing flight skills and other expertise they’ll require while on the space station.

“We first got to learn a lot of space science and engineering,” Saint-Jacques recalls. “We learned everything about the space station and what we might fly, and spent thousands of hours studying diagrams.”

There is also Russian language training, because half the crews on the space station are Russian and all astronauts leave Earth on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, at least until NASA develops a new spacecraft to replace the space shuttle (which is expected to happen in 2017). Russian is required to communicate with cosmonauts and also to ride in the Soyuz, which, naturally, has fully Russian controls. Astronauts need to pass challenging oral and written exams to be qualified to use the spacecraft.

As Canadians, Hansen and Saint-Jacques are especially aware of the importance of space robotics. Canadarm2 is sometimes used for spacewalks on the station, when crew members need to heft equipment or travel long distances. On Earth, one location where astronauts train for Canadarm2 is in simulators in the CSA headquarters in Longueuil, Que., east of Montreal. There they learn how to keep adequate clearances for astronauts during spacewalks, or how to capture spacecraft, among other manoeuvres.

“Sometimes the arm operator can’t see the clearances between the arm and the structure to make sure they’re not hitting anything, so they require the assistance of the spacewalkers,” Hansen says, pointing out that the crew member operating the Canadarm2 can’t even see his or her own feet. “There’s a lot of communication involved and a lot of teamwork.”

More recently, Canadarm2 has been adapted to catch new spacecraft — such as SpaceX’s Dragon — as they arrive at the ISS. Astronauts do virtual practice runs on the ground and even in orbit to prepare for these crucial cargo spacecraft, which carry food and supplies to the crews.

Before heading into the close confines of the ISS for a typical six-month mission, space agencies must make sure their astronauts can function in isolated and confined environments. NASA uses an underwater laboratory called Aquarius — located off the coast of Key Largo, Florida — for its NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) that typically have about six people living underwater for up to three weeks. Both Saint-Jacques and Hansen have participated in the NEEMO program.

Astronauts also participate in survival training such as an “off-nominal” (not part of the primary mission objectives) Soyuz landing scenario in Russian wilderness. In 2012, Saint-Jacques and two cosmonauts worked together to find food and make a shelter in –25 C, with only the descent capsule’s contents and parachute and a survival kit including a machete, waterproof matches, flares, a radio, six litres of water, a compass, a bit of food and a first aid kit.

Although astronauts are used to isolated environments and psychological hardships by the time they fly, they have private medical conferences with their doctors once a week and private psychological conferences every two weeks while in space, just to check in on anything that might be bothering them. Problems are rare, emphasizes Raffi Kuyumjian, the CSA’s chief medical officer for operational space medicine, but the doctors are also trained to listen for signs such as tense voices during normal ground communications.

Astronauts are trained on all the exercise equipment aboard the ISS, which includes a treadmill, an exercise bike and a resistive device that uses piston-driven vacuum cylinders to simulate weightlifting. They spend roughly two hours a day in orbit (and varying amounts of time beforehand, depending on the training program) exercising. Most of the Earth-based physical training takes place at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, but frequent exercise continues no matter where the astronauts are.

Canada’s astronauts communicate with their doctors by phone or video conference during training, although a specialist flies to Houston to be with them for a week once every six to eight weeks, explains Natalie Hirsch, the project officer for space medicine at the CSA. “In a sense it’s quite good, mimicking what the support will be like while in space,” she says. “We have to work with them from a distance anyway.”

After getting into space, it usually takes three to four days for astronauts to get used to being in orbit. They are encouraged to take it slow at first during exercise, then ramp up. “Every exercise program is based on a standard template, but ends up being individualized for each person depending on preference and fitness level,” says Hirsch. That’s when the combination of resistance and cardiovascular training is most crucial, to lessen some of the negative effects that microgravity has on the body — such as muscle and bone loss — and keep them fit.

Both Saint-Jacques and Hansen are regular CAPCOMs in NASA’s Mission Control, serving as the voice link between the ground and the ISS. They are also called on to attend meetings and take part in spacewalk procedure rehearsals for missions. They also supported Chris Hadfield’s famous spaceflight in 2012-13 by attending meetings on his behalf and becoming familiar with his mission.

The astronauts have not been assigned to a flight yet, but for now they’ll remain on the ground getting ready for space and supporting other missions. Because astronaut time on the space station is based on a country’s contributions, and Canada is a minority contributor, another spaceflight for a Canadian astronaut isn’t expected until about 2017 or 2018.

The astronauts are scrutinized and evaluated for future assignments at every step. But Saint-Jacques says competition within the corps itself is low. “We are competing with high standards you can’t achieve on your own, and you have to help each other. I couldn’t conceive of a life of competing with my friends for years.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

Exploration

The significant CSA events since Alouette’s launch

Exploration

A conversation with Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques, who is getting ready to travel to the International Space Station

People & Culture

This year’s roster of Gold Medal recipients at The Royal…