Kids

Giant floor maps put students on the map

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

- 1487 words

- 6 minutes

Mapping

“When the craft got into shallower water, the Royal Marines lowered the door. The three in front of me including Doug Reed were hit and killed. By luck I jumped out between bursts into their rising blood. Cold and soaking wet, I caught up to Gibby?… the first burst went through his backpack. He turned his head grinning at me and said, ‘That was close, Dougie.’ The next burst killed him.”

Scenarios such as this, which Canadian soldier Doug Hester described for the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada regimental archives, played out across Juno Beach to terrible but ultimately triumphant effect on D-Day, the 75th anniversary of which is today.

Hester was among the 14,000 Canadians who landed on the Normandy beach on June 6, 1944, as part of the Allied invasion of Europe, and he and his fellow soldiers, most of whom were untested in battle, were probably familiar with maps like the one pictured here.

Issued by the British Admiralty about 3½ months before the invasion, the map shows soundings in fathoms, “conspicuous objects circled in red” — churches, water towers and the like — and the five zones where six Canadian regiments — the Queen’s Own Rifles, the Regina Rifles, the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the 1st Hussars and the Fort Garry Horse — were the first ashore: Mike Green, Mike Red, Nan Green, Nan Red and Nan White, where the Queen’s Own Rifles landed.

Like most of the Canadians fighting that day, Hester and his regiment encountered stiff resistance from German forces whose defences had been largely unaffected by the pre-landing bombardment. Still, by the end of the first day, the Canadians had secured the beach and cleared German troops from Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer, and advanced farther inland than any other troops. Their success came at a cost, though, with 1,074 casualties, 359 of whom were killed. The Queen’s Own Rifles suffered the greatest loss of any Canadian unit on D-Day with 61 men killed. Hester himself was one of only three survivors from the regiment’s 10-man B Company.

The Juno Beach landings were one of the first steps in the long march toward the end of the Second World War. But for Canada, they were also an opportunity to distinguish itself, as military historian Mark Zuehlke writes in Juno Beach: Canada’s D-Day Victory: June 6, 1944, “Five Allied divisions landed that day — two American, two British, one Canadian. A David hit the beach alongside two Goliaths and did as well or better than the giants.”

*with files from Erika Reinhardt, archivist, Library and Archives Canada

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

Mapping

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.

Mapping

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps

Mapping

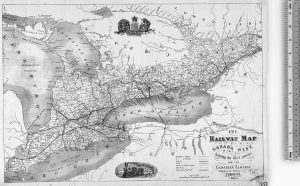

Early maps of the railways that shaped our country