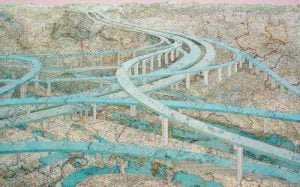

Mapping

Inside the intricate world of video game cartography

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.

- 2569 words

- 11 minutes