Travel

Trans Canada Trail celebrates 30 years of connecting Canadians

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

- 1730 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Think about nation-building projects in Canada, and one of your first thoughts is likely the transcontinental railway completed less than two decades after the country was born — a monumental effort that connected growing communities and industries across the nation.

When Canada turned 125, another ambitious project sought to further knit the country together. This time, a trail that would link our three oceans and celebrate the historic waterways, protected ecosystems and bustling towns and cities.

It may have seemed fanciful then, but today, as that dream turns 25 and the nation turns 150, the trail is about to be fully connected from coast to coast to coast — an achievement that’s being touted as one of the greatest gifts Canadians could share with each other and the rest of the world.

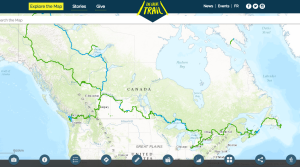

Back in 1992, it was the Trans Canada Trail, a name still carried by the non-profit organization that coordinated efforts to connect the trail from the beginning. Now, it’s called the Great Trail, reflecting its evolution from bold dream to physical reality. It’s already the world’s longest recreational trail network, and it will stretch nearly 24,000 kilometres when fully connected by the end of 2017.

“It’s a tangible link and a tie that binds us together,” says Deborah Apps, Trans Canada Trail CEO and president. “What better gift can we give to each other than a national trail that connects us all?”

While the railway facilitated Canada’s economic ambitions, the Great Trail celebrates its natural splendour. Spanning every province and territory, it links nearly 430 separate trail sections, each an ecological and cultural gem in its own right — from urban to wilderness, waterway to roadway. It passes through historic settlements that grew from collisions of cultures; it showcases the railway’s legacy of trestles and tunnels; it follows paddling routes that supported First Nations for generations and spurred the fur trade long before Canada was Canada.

The trail network can be appreciated by anyone, and its multi-use trails can be accessed by foot, bicycle, horseback, canoe or kayak, skis or snowmobile. You’d be hard-pressed to find a better way to explore the country.

Although connecting the trail is a national endeavour, the individual sections are owned and maintained by local groups, driven by the passion of volunteers. They are gearing up to celebrate linking the trail’s full length in 2017, and also busy writing the Great Trail’s next chapter. “Connecting it is one thing, but we’ve really only scratched the surface,” says Apps, who adds that the organization’s next step will be engaging Canada’s youth to get them even more involved — not just to explore the trail, but to shape its future. “We hope to explore this ‘living lab’ concept of using the trails to teach our youth about nature and the environment.”

Apps says people from as far away as the United Kingdom and New Zealand want to emulate the trail concept in their own countries, and that each day more Canadians inquire about getting their communities involved.

“Who would have thought we’d be able to do this in 25 years, but we have,” she says. “It’s just going to get better. To be able to stand on the trail anywhere in Canada and know you’re connected to everyone else along it — that’s a pretty good feeling.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Mapping

As Canada's most famous trail celebrates its near completion, Esri Canada president Alex Miller discusses the ambitious trail map that is helping Canadians get outdoors

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it

Places

It’s an ambitious plan: take the traditional Parks Canada wilderness concept and plunk it in the country’s largest city. But can Toronto’s Rouge National Urban Park help balance city life with wildlife?