Travel

Trans Canada Trail celebrates 30 years of connecting Canadians

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

- 1730 words

- 7 minutes

Travel

An ancient Mi’gmaq migration route that follows the Nepisiguit River's winding route to the salt waters of Chaleur Bay, the Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail is now one of the world’s best adventure trails

The seatbelt pressed into my shoulder as our driver stood hard on the brakes. Light objects flew about inside the 20-year-old Corolla. From my spot in the back seat, I saw the mother black bear crossing the highway, followed by a trio of cubs. A slow fourth cub turned back, and we passed between it and the others.

In the front seats were driver Wade and John — two friends I hiked with regularly. We lapsed back into quiet. Roadside signs warned frequently of moose, and our eyes scanned the darkening evening forest.

We were on our way to Bathurst, New Brunswick. There, a driver would shuttle us the final 160 kilometres to Mount Carleton Provincial Park. From there, our adventure would begin, hiking the 160 kilometre Nepisiguit Mig’maq Trail to it’s end at Mowebagtabāāg (Chaleur Bay).

The last time I’d visited this place — Mount Carleton Provincial Park — I was a child, no more than ten years old. I remember a long dusty drive on a rough gravel road to a park that, for a boy in the early ‘80s, felt infinitely remote. I recall a swim in a lake with a lakebed I’d been told was quicksand. Quicksand, in fact, went on to occupy a large place in my boyhood imagination.

As forecast, the winds increased throughout the evening, remnants of an early August hurricane. By the time we found our lakeside tent platform — well past midnight — angry warm gusts made pitching tents a challenge. The tone of the storm ratcheted higher and trees contorted, cracking audibly above the roar of the wind. The platform rocked up and down as tree roots moved beneath it. An especially loud gust sent me rolling onto my side, grimly hopeful that it would make a better position from which to receive a falling tree.

The combination of excitement and discomfort led to fitful sleep. I awoke around 3 a.m., thirsty, having finished my water on the long drive. I tried to ignore the sensation, then got up and made my way down to the lake. The wind was still high but the worst seemed to be over. In the darkness of the lakeshore, the surrounding low mountains loomed, inky masses. A big moon shone through broken clouds that scudded across the sky, whitecaps visible against the darker shades of lake and hill.

The possibility that this lake could be the same one I swam in during my youth floated through my mind. I was surprised by the temperature of the lake water — tepid, warm even. It was water I guessed bacteria would enjoy, and I was glad to have my filter. It had been an exceptionally hot summer and the lake — called Lake Nictau — had clearly absorbed a lot of heat. No sign of quicksand.

Day one dawns fine and sunny. The storm had been a fast-moving one and the wind had dropped almost completely. A friendly park worker drove us to the trailhead. Conversation switched back and forth between English and French, as is common in this region of New Brunswick. The truck radio crackled; the storm had caused damage.

We were here — the trailhead, and the beginning of the Nepisiguit River, where it springs from its lake headwaters. We would walk its south bank for nearly 160 kilometres, flowing with the river back to the sea — and our car — at Bathurst.

The first steps of a hike are a moment to be savoured: the planning is done; the drive is over; physical training is complete. Your kit might include some new elements, or maybe only the tried and true. But you are about to stretch your legs. Unknown landscapes and experiences lie before you. You will be tried, and you will be rewarded.

The Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail leads hikers through some of New Brunswick’s best-preserved and most scenic wild landscapes. Developed over many years in a phased process, it bills its length officially at 150 kilometres, but our GPS had us adding a few. We planned on averaging 30 km per day on unknown terrain, to complete the trip on day five.

This river, and the lands that surround it have been part of the unceded traditional Mi’gmaq territory for millennia. Nepisiguit is said to come from an older word meaning ‘roughly flowing water’ in the Mi’gmaq* language. The trail name celebrates the Mi’gmaq heritage of the river and the lands it winds through. The nearby community of Pabineau Mi’gmaq First Nation was instrumental in trail development and continues to be involved in several aspects of its management.

While the route is ancient, the modern Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail came into being through persistence, cooperation and hard work by an extended network of people, many of them volunteers. In 1985, work was initiated by Pabineau Mi’gmaq First Nation following a study funded by the Canadian Forest Service. In 1998, the first section of revamped trail near Pabineau Falls was opened. Despite initial enthusiasm, further development of the trail wasn’t commissioned and the section soon languished. In 2004, a group called “Friends of the Mi’gmaq Trail” began to advocate for trail development, and by 2014 momentum had built in earnest. This was largely thanks to social media, which amplified the efforts of volunteer trail builders, says Rod O’Connell, an active member of the trail board of directors involved since the beginning. “Dr. Samuel Daigle was part of a group who really got a lot of volunteers engaged, often through Facebook. The word would go out, and there were always people showing up to work,” says O’Connell. In 2018, The Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail finally opened.

Beginning at the trailhead within the boundaries of Mount Carleton Provincial Park, we had chosen to hike the trail in an easterly direction. While it can be hiked from either end, our main reason for doing it downstream was the convenience of leaving our car at Bathurst, and the efficiency of getting a shuttle one way. Hiking west to east also reduces vertical gain.

We awake the second day to cloudless skies and already-warm air. We’d camped the previous night on the banks of a branch of the Nepisiguit, beside a rusted single-lane bridge. While we’d initially pitched our tents only a few inches above the river’s rapids, heavy thunderclouds rolling in convinced us to move to higher ground. Waking in the night to a rising river was not worth the risk. The rain didn’t come, though I did awaken to a light shining on my tent — so bright I thought it was a flashlight. I soon realized it was the almost-full moon and dozed off again.

We begin the day walking through dry tall stands of pine and spruce, the trail almost white with hard gravel and sandy soils. In this heat, the white earth and dry pines give the landscape an almost Mediterranean quality.

We move into a stretch of lazy, calm river. The landscape flattens, but we see rounded hills a few miles to the south, which our map calls the Christmas Mountains. The land turns to low marsh and the trail leads us over beaver dams, which serve as bridges. Looking at the landscape, I am struck by an understanding it evokes. The trail we tread and the river beside us have been central to the lives of Mi’gmaq people for hundreds and thousands of years, as a travel route, but also as a source of sustenance, for tens and hundreds of generations. This historic artery into the heart of the New Brunswick wilderness is rich in cultural sites. At Indigenous archaeological sites along the river, stone tools dating from 5,000 years BP have been discovered. Today, rock blinds created for hunting caribou can still be seen. Caribou were present here in the early 20th century, with the last New Brunswick sighting reported north of Nictau Lake in 1928.

Chief Terry Richardson of the Pabineau First Nation talks with pride as he describes the Mi’gmaq connection to the Nepisiguit River. “The Mi’gmaq trail means a lot to the First Nations in the region, specifically to the Pabineau First Nation,” says Chief Richardson. “This was the route that many of our ancestors travelled to gather, hunt and travel throughout the province. To see this trail now being used to promote wellness and for people to enjoy the nature of the trail brings much pride to our community and our involvement in not only having the trail on our lands but our participation in upkeep and developing the trail initially is even more special.”

Chief Terry Richardson, Pabineau First Nation“This was the route that many of our ancestors travelled to gather, hunt and travel throughout the province. To see this trail now being used to promote wellness and for people to enjoy the nature of the trail brings much pride to our community.”

Now the river is rocky, with large boulders surrounded in foaming water. Tall white pines tower over the opposite bank. We begin to climb, away from the river into a forest composed solely of jack pine and caribou moss, a landscape created by forest fire.

Afternoon sees us in stands of big eastern white cedar, the largest I have ever seen in Atlantic Canada. The river is visible through the stand, as the land slopes away to our left. The heat and the miles slow our pace. We stop to make cold coffee at an icy spring-fed stream.

As evening begins, the long day and many miles have us searching for a campsite. For miles more we walk, seeing no ground flat enough for one tent, let alone three. We press on, considering several sites, but finding none worthy of stopping, until we round a corner to find a patch of soft flat ground which has hosted many campers. Beyond, large smooth, flat rocks jut out into the river which burbles gently around them. A gem of a campsite.

Tents are pitched. We settle onto the rocks to make supper. I cook noodles with parmesan, olive oil, basil, and bacon. The sun sets and the spruce on the far bank are silhouetted, coal-black, by the evening sky beyond. As the air cools, the rocks are warm beneath us. We make a small fire by the water’s edge and enjoy some whisky. The first faint stars appear. Common nighthawks emerge over the river where they dip and veer in a show of acrobatics as they chase insects invisible to us.

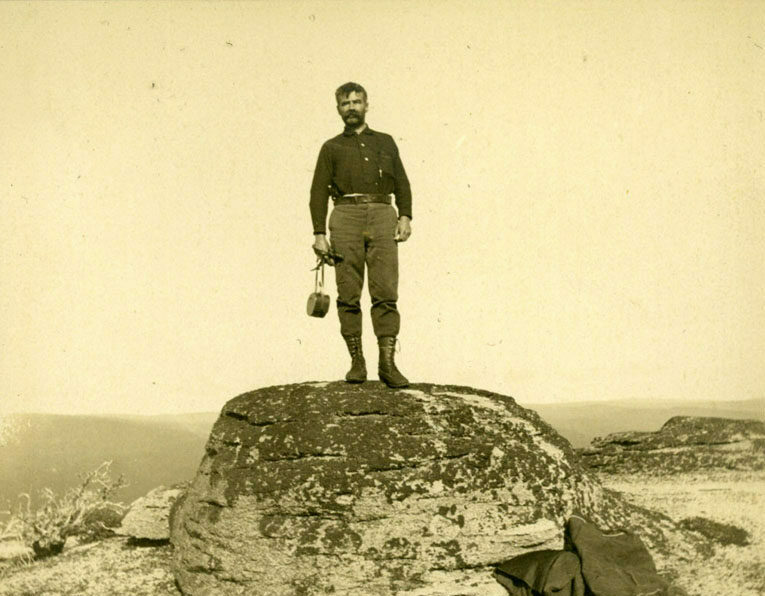

The pull of this land is not only the possibilities of adventure it provides, but also its astounding flora and fauna. From 1882 until 1929 — a span of almost 50 years — scientist and adventurer William F. Ganong spent every summer travelling the wilderness of his native New Brunswick. An avid explorer, his range of study was vast: botany, geology, physiography, human history, the province’s Indigenous Mi’gmaq and Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik) languages, and more. His numerous publications contributed to knowledge of New Brunswick in many fields.

Ganong spent his career as professor of botany at Massachusetts’ Smith College. This allowed him summers for field work — trips which lasted up to three months — in the New Brunswick backcountry. He travelled mainly by canoe, but overland side trips on foot to explore areas of interest could last up to a week.

Throughout his long decades of outdoor travel, Ganong paddled nearly all New Brunswick’s rivers, but from his first visit there in 1898, the Nepisiguit held a special fascination for him. Much of Ganong’s work and travels are chronicled in Nicholas Guitard’s The Lost Wilderness and Ronald Rees’s New Brunswick Was His Country.

It’s day four.

Last night was spent in a teepee. The setting was unusual: an upland type of wetland with ice-cold springs all around. The area was marked by countless small channels of slowly-flowing water surrounded by moss, a forest oasis. After a huge day on the trail, the teepees, which include sleeping platforms, had been a welcome sight.

As we near Bathurst, we begin to see small cottages and cabins along the river. Late afternoon brings us to the next set of teepees, our home for the night once again. From the river’s edge nearby, we hear people talking and can smell a campfire. We leave our things in the teepee and make our way down the bank. Three canoes are pulled up on shore. We make the acquaintance of a family from France — a couple and their two teen-aged children who have just moved to Canada — and their guide and outfitter who runs his business from Bathurst. They’d spent the last two days canoeing down this section of the Nepisiguit. They share their ample drinking water and some bannock, freshly cooked over the fire.

Tomorrow will be hot again. With about 25 kilometres remaining, we decide to be on trail at dawn to take advantage of the cooler hours. In addition to the usual woods and single-track, the second half of tomorrow’s hike will combine former railbeds and side roads to lead us to the trail’s end.

We finish the day with a refreshing swim in the river, which is deep, slow, wide, and rocky here. From a cottage on the far bank, the sound of a summer party reaches us.

As we walk along the Nepisiguit on our fifth and final, we think back over the distance covered and the nature of this river, its many moods and landscapes. We began at its source, a lake whose waters flow beside us now. As we get closer to Bathurst, the river widens and slows. It will soon reach its destination and mix with the salt waters of Mowebagtabāāg, its course run. While the waters we see will soon join the sea, the river will continue as it has for eons, part of a great cycle.

In a world of growing development, there are so many pressures on lands and rivers like the Nepisiguit. I enjoy simply knowing it exists and take pleasure in the thought that I could return here. I am happy to hear of work underway to create a protected corridor along the trail to help ensure its conservation. According to O’Connell, roughly 85 per cent of the lands along the trail are now protected, in one of several ways — either in Mount Carleton Provincial Park, as part of the Nepisiguit Protected Natural Area, or in the new trail protected corridor, which varies in width.

We weren’t sure what to expect when coming to the Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail. We now feel blessed and fortunate to have walked here and gotten to know it. The Nepisiguit River has been important to people for millennia and has continued to hold a special allure for many. Just as these waters have shaped their own course, perhaps those who walk these banks are also shaped — if just a little — by the experience. For me, the word Nepisiguit will now conjure images as clear and indelible as any landscape I have been fortunate enough to walk through.

Long may it flow.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Travel

Immerse yourself in Viking archaeology and Basque whaling history while taking in Newfoundland’s scenic coastline and incredible geology

Travel

Discovering boats, buoys and deep-fried clams on an epic family road trip in the 2022 Chevrolet Traverse RS

Travel

Inspired by age-old travelways, a new canoe route knits together the Trans Canada Trail