People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

The temperature dropped to two degrees Celsius and the light from the midnight sun brightened gradually as we reached the northernmost point of the expedition. The GPS showed that we were at 78 degrees North and just beyond the horizon was a wall of ice stopping us only 720 nautical miles from the North Pole.

From there we headed to Thule; Greenland’s northernmost settlement. The name, which originates in Greek mythology, means “the end of the world.”

The surrounding landscape was harsh. Small glaciers and patches of ice are permanently merged into the bleak mountains and there is no sign of life or vegetation. The atmosphere seemed different there and we were getting used to strange light phenomena such as white rainbows and random patches of rainbow in the sky.

It was during this push northward that for the first time in our expedition we could definitively say that we were experiencing the effects of polar ice cap depletion. We sailed up through the infamous Baffin Bay and across Melville Bay through scattered icebergs where not too long ago ice sealed this region to all but the most ambitious captains. According to the Canadian Ice Service’s ice charts this region has never been so clear of ice at this time of year in recorded history. It beats 2011 and 2007 lows (years registered with lowest Arctic sea ice extent in recorded history), which saw on these exact dates large patches of middle pack ice still clogging the area.

It is remarkable to think that ever since English explorer John Ross’s 1818 voyage to Melville Bay, where his ships became trapped in ice, whalers and explorers have tried relentlessly to penetrate the pack ice of this area. They were trying to reach the North Water Polynya, an area of open navigable water at the extreme north end of Baffin Bay that opens up due to currents, so as to reach rich fishing grounds and most importantly the Canadian Arctic to find a possible Northwest Passage. Many expeditions never made it as far north as we had reached, being crushed by icebergs and the pack ice that only the most robust ships or fortunate ones could navigate.

Amundsen, the first successful individual to sail the Northwest Passage, crossed Baffin Bay during the 1903-1906 journey with his ship, the Gjoa, quite easily, but at the same time other ships like the SS Vega, the first ship to navigate the Northeast Passage, met its end in Melville Bay in 1903. Even as late as 1977, Willy de Roos, the second successful person in history to take a sailboat through the Northwest Passage, barely escaped the clutches of the ice of Melville and Baffin Bay. I wrote these words at the exact area where these ships and men fought the ice for their lives.

Thule marked the end of our time in Greenland and the beginning of the objective of the expedition: The Canadian Arctic. We received an increasing number of ice reports and the excitement onboard grew as we realized what we were getting ourselves into. The pack ice is breaking up day by day and we continue to study the charts and ice maps in order to plot our route through the Canadian archipelago where passages and openings are already beginning to emerge. We may be at the end of the world, but the adventure is just beginning!

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Environment

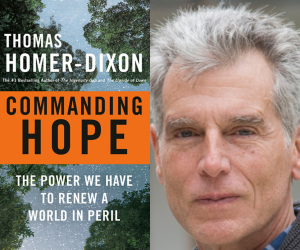

In an exclusive excperpt from his new book Commanding Hope, Thomas Homer-Dixon highlights four key stresses that inhibit society's collective sense of a promising future for our planet

Wildlife

How ‘maas ol, the spirit bear, connects us to the last glacial maximum of the Pacific Northwest

Places

“All the mischiefs humans and the universe are capable of inflicting on an ecosystem have conspired to attack the prairies.”