Enter the mentor-apprentice program and language documentation. Mentor-apprentice, the one-on-one immersion technique developed by Leanne Hinton, Matt Steele and Nancy Steele Richardson, who also wrote the mentor-apprentice bible, How to Keep Your Language Alive: A Commonsense Approach to One-on-One Language Learning, pairs a fluent speaker of a language that is no longer commonly spoken with a younger learner in a home or other culturally appropriate setting. There, the two speak only the language they’re focused on. Mentor speakers learn to convey messages without using English, and apprentices learn a few basic rescue questions and how to indicate a query with pictures or gestures.

Through the program, students get direction from Elders while also taking responsibility for their learning, preparing questions in areas of study, rather than waiting to be taught. A lesson might have the mentor making a pot of tea, with the apprentice prompting commentary about filling the kettle with water, lighting the stove, heating the water until it boils and so on. Writing notes during sessions is frowned upon, as apprentices must remain fully engaged in the focus language, but they are asked to keep audio recordings so they can listen and re-listen to lessons outside of sessions.

Heather Souter found the mentor-apprentice method through speaking with Bakker. Growing up in Vancouver, her father told her about their Métis history and culture, but there were no Cree or Michif classes at the University of British Columbia in the late 1970s when she attended. In the early 2000s, Souter was working as an interpreter and translator in Japan when she discovered Bakker and contacted him — a conversation that changed her life. Bakker’s work had contributed to a growing pride among Métis people, many of whom had been raised by parents and grandparents who had suffered violent racism and taught their children not to draw attention to their heritage.

The linguist pointed Souter to the mentor-apprentice method and connected her with Michif-speaking Elders Rita Flamand and Grace Zoldy. When they agreed to teach her, she took both of them and fellow learner J.C. Schmidt to California to learn the mentor-apprentice program from Hinton and Richardson.

Souter also studied with other Indigenous language revitalization experts in the U.S. before moving to Camperville, Man., to apprentice with Zoldy and Flamand (who died in 2016). Souter went on to do a master’s degree in Indigenous language revitalization in Saskatoon through the University of Victoria and partnered with local speakers, including Verna Demontigny, to start a non-profit group, Prairies to Woodlands Indigenous Language Revitalization Circle, and to train mentor-apprentice pairs, mostly relatives who have the benefit of relationship, trust and access to each other.

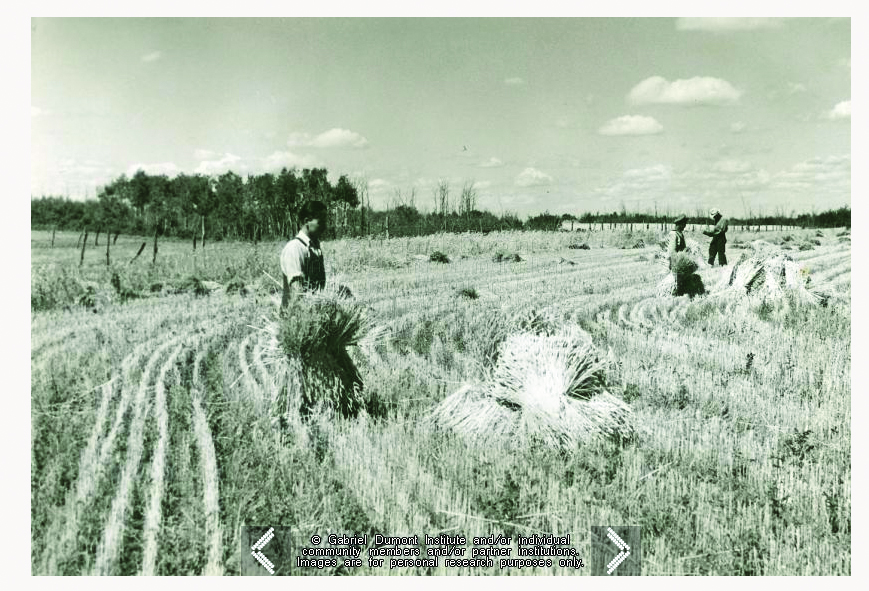

Demontigny grew up in a road allowance community called “li Kwaen” (meaning “the corner”) near Binscarth, Man., and spoke only Michif until she began school. As much as she loved speaking her language, Demontigny did not teach her children Michif because she didn’t want them to suffer the ridicule and discrimination she had endured. Though she didn’t pass the language to her children, she has become a voice for Métis culture and language, giving school and other public presentations. When the revitalization circle received funding to run a master-apprentice program, Demontigny and her son Elvis were among six pairs who signed up. They have spent up to 12 hours per week for the past two years living in the language.

“You’re literally not speaking English at all, just pointing or using pictures or cooking or shopping, doing the laundry. There’s steps: you sort the laundry, this pile is white, there’s colours. It’s a lesson all itself,” she says. “We learn the language through everyday living.”

Demontigny has seen Elvis’s confidence grow as his understanding and ability expands. “He’s proud now because he knows the language and because the culture comes [with it]. He never realized it was our culture he lived. It gives him a lot of pride. It makes me feel proud. I fulfilled my obligation to him because now he knows who he is,” she says.

Elvis is now teaching his daughter Michif, while Demontigny is passing the language on to her other son and his family.

Along the way, Souter met Dale McCreery, who was in the first semester of his master’s degree in linguistics at the University of Victoria. Souter recruited him to the project, and linguist Nichole Rosen asked him to also document the Michif language for future learners, which led him to apprentice with Grace Zoldy. McCreery was the ideal candidate for the two-jobs-in-one position. At 26, he already spoke five languages and he had grown up listening to his Métis grandfather speaking some of the Cree words he remembered. McCreery had taught himself some Cree over the years from books his grandmother had given him.

When he started university, he received some Métis student funding that brought his grandfather to tears.

“He said, ‘it’s the first time being a half-breed has ever done any good for anyone in my family,’” says McCreery.

In preparation for his 2009 summer of immersion in Michif, McCreery brushed up on his Cree, which provided a foundation in the complex verbs used in Michif. McCreery stayed at Zoldy’s cosy house on the edge of Camperville, near Lake Winnipegosis, for about four months and returned twice over the next two years, doing the intense and rare work of learning the language while formally documenting it for future learners.

“Our goal wasn’t just to learn. It was to make recordings of all the learnings that would be comprehensive enough that another learner could come by afterward and listen to them and learn the language themselves,” he says.

McCreery, now a PhD candidate focused on best practices in language documentation for the purpose of effective teaching, says Michif is on the brink of “going to sleep,” the term linguists use instead of saying a language is disappearing or dying. And with so few elderly Michif speakers, focusing on classroom teaching is not the best use of scarce language revitalization resources, he says. Learners need intensive time using the language with fluent speakers. Likewise, books and social media posts are excellent for sparking the passion to learn a language but, in and of themselves, will not create fluent speakers. At best, 50 or even a few hundred hours of instruction will produce a beginner speaker: fluency takes thousands of hours of conversation and study, says McCreery.