Environment

Last bastion of ice

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

- 2894 words

- 12 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Tough, yet fragile. Ancient, yet vulnerable. Cold and inhospitable, yet strangely beautiful. The contradictions inherent in ice and the landscapes it calls home have inspired many artists, photographers and writers over the last 200 years. Now climate change threatens many of these landscapes, adding yet another layer of nuance to this rich body of work. All this is on display in Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes in Art, 1775-2012, an art exhibition currently making its way across Canada.

The exhibit shows climate change in a new way, says Barbara Matilsky, the curator behind Vanishing Ice. “Many people are aware of the critical importance of ice for the planet,” she says, adding that she wanted to focus on how the artistic legacy of ice has helped shape Western views of the natural world.

The exhibition — which contains over seventy works by fifty artists from twelve countries — begins a three-month run on Saturday at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario (before this, it visited Calgary’s Glenbow Museum.)

Because it covers a span of over two centuries, the exhibition provides some unique opportunities to see changes, both in the icy landscapes themselves and society’s view of them.

Above: Arthur Oliver Wheeler (Canadian, 1860—1945), Athabasca Glacier, Jasper National Park, 1917, printed 2013, Black-and-white photograph, 35.6 x 50.8 cm, Courtesy of the National Archives of Canada. Below: Gary Braasch (American, b.1950), Athabasca Glacier, Jasper National Park, 2005, Archival inkjet print, 35.6 x 50.8 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Portland, Oregon>

For example, Edwin Landseer’s Man Proposes, God Disposes, painted in 1864, shows vicious polar bears picking over the remains of the doomed Franklin expedition. But as melting ice threatens their lifestyle, polar bears have instead become symbols of the Arctic’s fragile ecosystems. This vulnerability is mirrored by the haunting juxtaposition of two images of the Athabasca Glacier in Jasper National Park; between the time of Arthur Oliver Wheeler’s 1917 photograph and Gary Braasch’s 2005 copycat, the glacier has retreated by more than a kilometer and lost nearly half its volume.

The exhibition also highlights the historic partnership between art and science.

“Artists awaken the world to both the beauty and increasing vulnerability of ice, which is critical for biological and cultural diversity,” says Matilsky, who recreated the 5000-mile iceberg-hunting expedition of 19th century landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church in 2008.

Many of the earliest polar paintings come from artists who tagged along on research expeditions to document the journey for audiences back home. That tradition continues today, with modern granting agencies providing room for artists and writers to work alongside scientists.

One moving example is Lita Albuquerque’s Stellar Axis, Constellation 1, which was created with the support of the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. The piece shows 99 ultramarine spheres on Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf, mapping out the positions of southern constellation that cannot be seen during the 24-hour sunlit day. A year later, Albuquerque created a complimentary installation at the other end of the globe, calling attention to the beauty of the poles and the axis between them.

“In many ways, an artist’s creative process resembles that of a scientist: observing, looking for patterns in the natural world, and interpreting the results,” says Matilsky. In return, artists “offer scientists a way to communicate their ideas to the public on more visceral, emotional, and spiritual levels.”

But whether you’re a scientist, geographer, artist or some combination thereof, Matilsky hopes that the exhibition will both inspire people and motivate environmental activism.

Vanishing Ice was created at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington.

Lita Albuquerque (American, b. 1946), Stellar Axis, Constellation 1, 2006, Archival inkjet print by Jean de Pomereu, 53 x 120 cm, Whatcom Museum, Gift of Jean de Pomereu, 2013.17.2

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

Environment

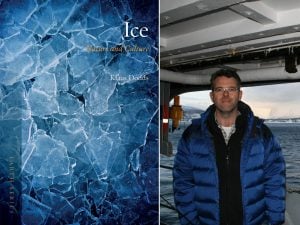

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

People & Culture

A century after the Group of Seven became famous for an idealized vision of Canadian nature, contemporary artists are incorporating environmental activism into work that highlights Canada’s disappearing landscapes