Wildlife

The (re)naming of caribou

The failure to recognize distinct species and subspecies of caribou is hampering efforts to conserve them. So, I revised their taxonomy.

- 1540 words

- 7 minutes

Wildlife

After more than a million years on Earth, the caribou is under threat of global extinction. The precipitous decline of the once mighty herds is a tragedy that is hard to watch — and even harder to reverse.

Caribou make do. They use as little as possible, often what nobody else wants. They perfected this impulse over tens of thousands of years, chasing north after retreating ice sheets while most other hoofed animals stayed further south, or spreading themselves thinly across scraps of land in forests and valleys and on mountaintops.

They even learned how to survive the privations of winter by subsisting on lichen. Platter-sized hooves — ersatz snowshoes — support them on the snow to reach it on high. Shovel-shaped antlers help some of them dig snow craters to find it down low.

But getting to the lichen is only part of the survival trick. Caribou also need to squeeze every last bit of nutrition out of the protein-poor food, which means they had to figure out how to reuse their own urea, a chemical byproduct of metabolism,

a little like us being able to drink the same cup of coffee twice to get every smidgen of caffeine out of it. The feat continues to impress evolutionary biologists.

Suffice it to say that Rangifer tarandus is built for survival. Females even limit themselves to the birth of a single calf each year, the better to husband resources.

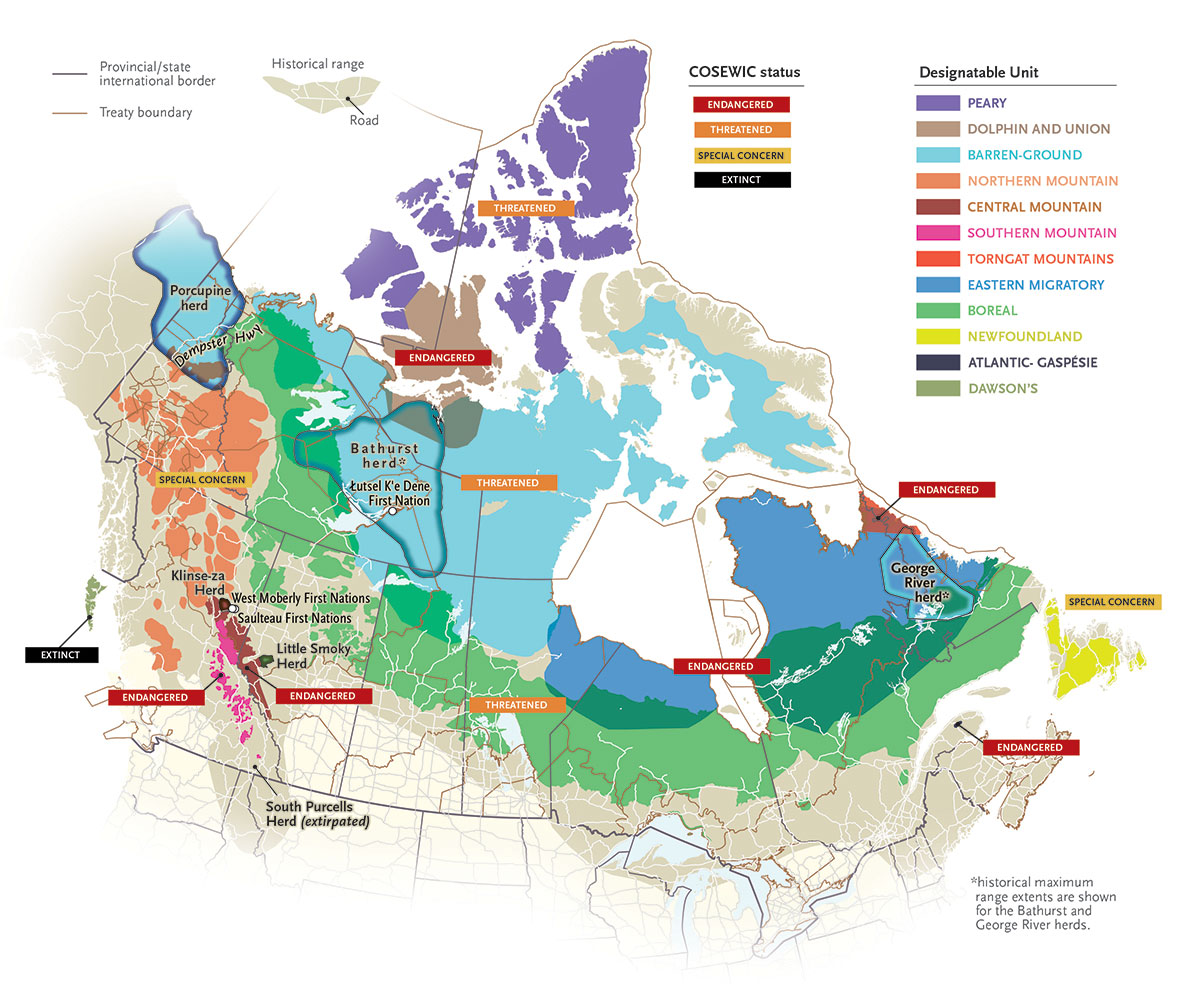

Yet today, after more than a million years on Earth, the caribou, also known as the reindeer, is under threat of global extinction. In Canada, where the animal is such a national icon that it graces our quarter coin, the species is in ominous shape. Of a dozen ecologically distinct populations (called “designatable units” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada), one is extinct, six are endangered, three are threatened and two are of special concern.

It’s not just a bleak picture; it’s also getting worse. That’s despite huge efforts by conservationists and Indigenous Peoples, streams of scientific analysis, dozens of provincial and federal legal instruments designed to protect caribou, plus lots of money, brainpower and passion. It’s like watching a boulder roll down a hill. Only one designatable unit, the little white Peary caribou of the Arctic islands, has improved recently, going from endangered to threatened in the committee’s rating system.

“I haven’t given up on caribou, but it’s hard to watch,” says Chris Johnson, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George. He is co-chair of COSEWIC’s terrestrial mammal subcommittee. “We’ve been ringing the alarm for years.”

Take, for example, the barren-ground caribou, one of the two main types (the other is woodland caribou). These are the vast Arctic herds that still make the longest land migration in North America, pounding their way across the tundra to get to their calving grounds in the North, where females give birth within a few days of each other. The mass trek and group maternity ward is a strategy to keep wolves at bay through the power of congregation. In the mid-1990s, Canada had about 1.8 million barren-ground caribou. By the time the committee assessed them in 2016, a solid million had vanished.

“The magnitude of the decline is breathtaking and irrefutable,” says Johnson. “We’re just not finding caribou like we did back in the ’80s and ’90s.”

Is it climate disruption, which fiddles with so many of the systems caribou rely on for their delicate dance of survival? Is it too much hunting? Too many wolves? All those roads, seismic lines, mines, oil and gas drilling? The clear-cutting? The general creep of human reach? Our insouciance? Our greed?

More important, can it be stopped in time to keep caribou on the land? The answer is simply unclear.

The worst prophecies are already coming to pass. Earlier this year, John Krebs, a provincial biologist who is director of resource management for the Kootenay boundary region in southeast B.C., bore witness to the bitter end of the South Purcell herd, one of the 14 remaining isolated populations in the endangered southern mountain designatable unit.

Krebs had been watching the herd decline for nearly three decades, starting in the ’90s when he was a wildlife biologist working for the province’s electric utility. Back then, there were about 80 caribou tucked away in the forests of the South Purcell Mountain just north of the United States and west of Alberta. That was already considered too few for a healthy herd.

Biologists radio-collared some to track their movements. Provincial policy-makers enacted a cascade of attempts to protect the herd’s core habitat, including restricting road building and snowmobiling. But the herd’s numbers dropped like a stone anyway, reaching perhaps a couple of dozen in the late 1990s.

“It was surprising how quickly it happened,” says Krebs. “Sometimes we felt, did we miss the herd in our survey?”

By 2012, the South Purcell herd was in such tough shape that Krebs and other biologists organized a transplant of animals from another herd to bolster numbers. It was an abject failure. Within a couple of years, all the transplants were dead. By 2019, the South Purcell caribou were down to just five animals.

That’s when Krebs and his team took four of the remaining animals to a maternity pen near Revelstoke, B.C., in the hope that they would eventually have the chance to join a new herd further north. A single caribou remained in the South Purcell Mountains, an old bull who was far too big and ornery to move.

“The viability of the herd has been gone for a while, but the last marker was this bull,” says Krebs.

Krebs tracked him, following signals from the animal’s radio collar, encouraged that he kept going. This past April, Krebs got the sign that the collar had stopped moving. On the last day of that month, fearing the worst, he and a colleague did a three-hour bush-crash trek into the forest to find out what had happened.

They found the bull caribou, dead and partly eaten. He had been jumped by two wolves and had made a final, messy dash through the forest before the wolves killed him. Later, a bear scavenged what was left.

When the caribou are gone, what’s left is ‘cascading ecological grief.’

“This was not only an animal’s last stand, and last moments, but it was the last of the herd that’s been on that landscape for thousands of years and was in First Nation oral history,” says Krebs, hesitating as he searches for words to describe the depth of his emotions. “It was profound to me, and I took a moment to take it in, in the bush there.”

The extirpation of the South Purcell herd was all the harder to understand because the area still has lots of prime caribou habitat, says Krebs. Time-honoured conservation approaches of saving landscape and limiting human activity just didn’t work to save the herd, or even its last bull.

“I felt not that we betrayed him but that we failed,” says Krebs. “We failed to recognize all the interplay among the factors.”

Watching one herd die out in real time is hard enough. But the South Purcell caribou are the seventh herd to disappear in southern Alberta and B.C. since 2003 alone, says Melanie Dickie, research co-ordinator at the caribou monitoring unit of the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, who is in the throes of PhD research on the species. She ticks off the names of the other six herds like a mantra of loss: Banff, Purcell Centre, Burnt Pine, South Selkirk, Maligne, George Mountain.

“We’ve been talking about doing something for the species for longer than I’ve been working on them,” she says.

it’s not just the southernmost caribou populations that are vanishing. Many are also in baffling decline across the planet’s northernmost reaches. Globally, numbers have crashed 40 per cent in just three caribou generations, from 4.8 million to 2.9 million, according to the assessment led by Canadian caribou biologist Anne Gunn for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s red list of endangered species. The findings resulted in the species being listed as vulnerable to

extinction in 2015, a first.

Some of the declines are happening because of changes to the land. Human activities sever migration routes and destroy habitat. “Caribou are creatures of space,” Gunn tells me. “They need that landscape.”

They’re also used to using those landscapes to get away, a prime evolutionary survival strategy. Now, human and other predators can get right to where they are, through roads and other conduits.

But other mechanisms for the drops in population are not perfectly clear. Climate heating could ramp up disease and parasites. Insect harassment of caribou, already a dangerous plague to mothers trying to rear calves on the tundra, is increasing along with the warmth. Caribou have been known to plunge panicked into the Arctic Ocean to escape the bites

of warble flies and nose botflies, or to run non-stop for hours in a frantic struggle to keep bugs at bay. Unregulated hunting in some parts of the world and slow government responses aren’t helping. And the trends are all going the wrong way, a signal that the declines could keep deepening, Gunn’s red list assessment concludes.

Gunn witnessed the problem in microcosm during the three decades she worked as a government biologist in the Northwest Territories. She resigned in 2007 and is now a B.C.- based consultant.

In 1986, the Bathurst herd, which once spanned the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and northern Saskatchewan and Alberta, numbered nearly half a million, abundant enough that Indigenous Tłı̨chǫ hunters alone could depend on taking 14,000 animals a year for food food security.

By 2018, the herd’s total population had crashed to about 8,000. Despite the trend, which scientists first described in 2003, sport and resident hunting of the Bathurst herd continued until 2010. By 2016, even the tiny Indigenous subsistence hunt of 300 animals had to be cancelled. There just weren’t enough caribou.

“I’m glad I’m not a biologist up there,” says Gunn. “It would be a heartbreak to see an empty landscape.”

Losing caribou is about a lot more than losing a species. Caribou are known as an “umbrella” species, which means that when they are present, so is living space for thousands of other creatures, says wildlife ecologist Robert Serrouya, director of the caribou monitoring unit at the University of Alberta. Watching the disappearance of caribou therefore also comes with the understanding that their loss is linked to the unravelling of a complex, interconnected web of other possible losses, big and small. What about lichens, and the 250-year-old trees they grow on? Mosses? Tiny insects? When one piece of the puzzle goes missing, the effects ripple across the ecosystem.

The loss is ineffably personal as well as ecological.

“There’s a spiritual connection to knowing we have something that’s history, that’s not changed and not modernized for thousands of years,” says Serrouya.

And then there’s the bigger scientific picture. Caribou are not the only species on the brink. As they vanish, they serve as a reminder of the planet’s extraordinary ongoing pulse of extinction. A comprehensive report in 2019 by an international team of scientists with the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, known as IPBES, found that a million species are in danger of going extinct, more than at any other time in human history. And the rate of extinctions is speeding up.

But for Indigenous Peoples who have relied on caribou for generations, the loss is far more than personal or metaphoric or scientific. Caribou reach across culture, identity, spiritual practice, family traditions and psychological health, say the authors of a new Inuit-led study on the loss.

“This is more than just about caribou as meat,” says Jamie Snook, executive director of the Torngat wildlife, plants and fisheries secretariat in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador and one of the report’s co-authors. “A lot of Inuit feel their time on the land is a determinant of well-being. It’s a protective factor for people.”

Snook recalls watching years ago as hundreds of caribou cavorted around a pond right in front of his cabin on Cape Caribou River in Labrador. They were everywhere, wild and unrestrained.

“It’s just so holistic to the patterns people have experienced over their lifetimes and generations. Once that all of a sudden disappears or is at risk, it really questions your identity,” he says.

When the caribou are gone, what’s left is “cascading ecological grief,” says Ashlee Cunsolo, dean of the school of Arctic and Subarctic studies at the Labrador Institute of Memorial University and another of the study’s co-authors.

“When you think about something as keystone as caribou, the tragedy is beyond comprehension,” she says.

Cunsolo and Snook had a first-hand look at the depth of the mourning during their study. As part of it, their colleague David Borish, now a postdoctoral student at the Labrador Institute, interviewed 84 people in the Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut regions of Labrador. The work will be released this year as a documentary provisionally called Herd.

People from the community agreed to tell their stories after the George River herd’s numbers plummeted and governments imposed a ban on hunting in 2013. The ban didn’t halt the decline. The migratory woodland herd, once among the largest in the world with a recorded peak of 780,000 animals in 1993, shrank to 8,900 in 2016, a drop of 99 per cent, before sliding even further to about 5,200 and recovering slightly this year to 8,300.

The stories were harrowing. Not only have some young Labrador Inuit never tasted caribou meat, the staple food of their ancestors, but they also couldn’t distinguish a caribou from a moose. Older hunters grieved at not being able to teach young generations how to hunt and prepare skins and meat. They missed the conviviality of being out on the land tracking caribou, savouring the spiritual connection between hunter and prey.

“They had deep cravings for this meat and for this experience,” Borish says. “It was much more than just physical craving. It was an emotional craving to interact with this source of culture and pride they had had for so long.”

One man told Borish that the loss of caribou was hurting people all over, both body and mind, an acknowledgment of the psychological toll. Some wept during the interviews. They worry that the caribou are gone forever. So do Borish, Snook and Cunsolo. They fear that they have assembled final testimony about the Inuit relationship with caribou.

“What if there are no more? What if in 20 years, that’s it, we’ve witnessed the decline of something so important?” asks Cunsolo.

Can the caribou be saved? It’s like a three-dimensional puzzle whose pieces keep moving. And there are different answers for animals in different parts of the country.

Consider the Arctic’s Bathurst herd. Gunn and her colleagues at the international caribou group called CARMA (for the CircumArctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network) cite a dizzying range of assaults over the years that may have played a role in the herd’s collapse.

For one thing, the animals seem to have abandoned their former fall and winter ranges in the boreal forest, moving to the tundra instead. That means migration distances doubled, using extra energy. At the same time, mining exploration ramped up across the herd’s tundra home and five diamond mines opened. In the horrible hot summer of 2014, fire destroyed

11 per cent of their preferred winter range. The summers are warmer and droughts are more common, both characteristic of climate heating. These are ill omens for a creature so superbly adapted to the cold.

It adds up to more deaths — calves, mothers and bulls — and fewer births. And while caribou numbers have their own mysterious and often vast fluctuations, the CARMA group found that the herd’s cyclical decline was exacerbated by too much hunting and wolf predation. The balance of births and deaths went badly out of whack.

Repairing it requires killing wolves as well as restricting hunting for food, says Gunn. She is convinced that if communities near the Bathurst herd had begun killing wolves in 2010 when she recommended the practice, the herd would not have lost as many members and the food harvest would not have had to be reduced to zero. In fact, the wolf kill in that area began only last year. The practice is hotly controversial. The ?utsël K’é Dene First Nation opposes it, for example, saying it is inhumane.

But caribou herds have thresholds, says Gunn. Once the herds become too sparse, the animals’ social network is fractured beyond repair. When the animals can’t learn from each other, they become yet more vulnerable. It’s a recipe for extirpation.

Industrial activity likely plays a role in the fate of the Bathurst herd, too. To protect the caribou, roads need to be “permeable,” which means relying on convoys and interrupting traffic with daily road closures so the caribou can get across, says Gunn.

But the George River herd in Labrador and Quebec foundered even though there’s been little industrial activity near its habitat, says Snook. “It’s some complex combination of factors,” he adds. Meanwhile, in southern Canada, the dire effects of industry are incontrovertible. The logging of old-growth forests, oil and gas exploration, seismic lines, mining and even wind-power installations all disrupt caribou.

And those disturbances are increasing, despite myriad laws to protect the habitats of woodland caribou. During the dozen years ending in 2012, caribou lost twice as much forest cover as they gained throughout Alberta and B.C., according to a study by Serrouya, Dickie and others published in April. In the northern parts of the provinces, the loss came from forest fires; in the south, logging. And by 2018, those losses had intensified even more.

The one bright spot was that land-use regulations hashed out by the B.C. government in the mid-1990s to preserve some caribou landscapes actually helped a bit, the study found.

“It made things less worse,” says Serrouya.

Still, the woodland caribou are North America’s biggest conservation challenge on land, says Serrouya. A pressing issue is that all that logging opens up terrific habitat for deer, moose and elk, the other common ungulate species. The more other ungulates there are, the more wolves.

And here’s where the woodland caribou’s canny evolutionary strategy becomes a handicap. They evolved to protect themselves in the woodlands by living either alone or in small clusters, so tracking and hunting them wasn’t worth the energy for wolves. Now that wolves have such excellent access to moose, elk and deer in the same habitats where caribou are found, wolf numbers are up — and they encounter caribou more often even when they’re not specifically looking for them. It’s a numbers game.

“Caribou are like the french fries on the side of a hamburger meal,” says Dickie. “Wolves make their living off other ungulates, but if one bumps into a caribou, it’s going to eat it, because it’s food.”

“They are not just animals to us. They are our brothers and sisters, our friends and ancestors.”

Not only that, but more roads and lengthy seismic lines, which are narrow but ubiquitous corridors used to transport equipment to test for oil and gas deposits, make it easier for wolves to move long distances swiftly. That also increases the likelihood of running into a caribou.

“It’s kind of a double whammy there,” says Dickie.

The ultimate rescue is to create conditions for woodland caribou herds that allow them to be self-sustaining in the wild without heroics from humans. That means letting the forest grow old again, as well as letting nature once more take over the seismic lines and roads that serve as a handy conveyor belt for wolves. Together, these measures would reduce habitat for moose and deer, which would lead to fewer wolves and more caribou in, say, 50 to 100 years.

But right now, the situation is so precarious that taking only those long-term measures will condemn many of the most southerly herds.

“We need to spend a lot of money and public will and energy on conserving and restoring habitat,” Dickie says, “but we can’t pretend that it will magically solve the problem. We need to do some more drastic measures to make sure these herds are around in the short term.”

Maybe corralling pregnant females into maternal pens until they give birth and then releasing them back into the wild. Or perhaps creating a year-round captive breeding facility, although that’s still experimental. Or shooting wolves and culling other ungulates.

But the two approaches — habitat restoration and emergency rescue tactics — have to work in tandem, or else you end up with the heartbreak of the Little Smoky herd in Alberta.

To preserve its 80 or so caribou, sharpshooters take to the skies in helicopters each winter and shoot as many wolves as they can from the air, explains Mark Boyce, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Alberta. Then they drop strychnine poison onto the land to kill even more wolves. Each year, they kill between 100 and 120 wolves, along with the collateral damage of eagles, fishers, lynx, wolverines and the occasional bear. And they’ve been doing it for the better part of two decades, enough to keep the herd extant if not growing. But at the same time, the provincial government continues to approve oil and gas development in Little Smoky habitat.

“It’s a bit of a farce,” says Boyce, adding: “It’s the sort of thing you’re just going to have to keep doing forever because we’ve got a large population of wolves on the broader landscape, and so you go, whack, 100 wolves, and within weeks, they’ve been backfilled with wolves from an adjacent population.”

The most potent tool to protect the future of caribou would be for the federal government to issue an emergency order under the Species at Risk Act. That would allow federal rules to be applied to provincial lands, effectively halting logging and oil and gas development in caribou habitat. Is it merited?

“From a caribou ecology perspective, it is long past that time,” says Dickie.

But in 2018, when Catherine McKenna, then minister of Environment and Climate Change, recommended making an emergency order for the endangered southern mountain designatable unit (which then still included the South Purcell caribou), her federal colleagues balked, saying they preferred “a collaborative stewardship-based approach.” The 2021 federal budget, for example, proposed $2.3 billion over five years to help set up conservation measures for species at risk including caribou.

“We strongly believe that a collaborative approach will provide the best outcomes for species at risk conservation in Canada,” said Environment and Climate Change Canada’s spokesperson Samantha Bayard in an emailed response for this story.

Two sunny stories run alongside the portents of catastrophe. One is an illustration of the new approach the federal government advocates.

In 2013, West Moberly First Nations and Saulteau First Nations in central B.C. near the Alberta border embarked on a mission to save their 16 remaining caribou by setting up a mountaintop maternity pen and guarding its occupants from wolves until they can be released back into the wild — with radio collars and tags for monitoring. Since then, the nations have also been mapping caribou habitat and working to restore it, and culling wolves. Caribou biologists often cite the nations’ actions as one of the continent’s lone caribou recovery success stories.

By February 2020, the herd, now called Klinse-za, numbered more than 80, and the nations signed a 30-year partnership agreement with the provincial and federal governments resulting in two million acres of land in protected areas. The aim is to restore caribou habitat and help the herd become self-sustaining. It is the first agreement of its kind in Canada.

“They are not just animals to us,” West Moberly Chief Roland Willson said at the time. “They are our brothers and sisters, our friends and ancestors. The caribou have been suffering for decades as their habitat is destroyed piece by piece. They need us now, all of us. This partnership agreement gives us hope. It means that help is on the way.”

Up in the Arctic, the Porcupine herd has not had to recover. It is still thriving. It is the continent’s last great caribou herd, one of the legendary, migratory barren-ground populations. Every year, its 200,000 or so members race en masse across northern North America to the Arctic coastal plains to give birth.

Part of the herd’s success is that its calving grounds in Yukon and Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge are protected from development, at least for now. (Former U.S. President Donald Trump auctioned off oil and gas leases in the refuge during the final weeks of his tenure, and current U.S. President Joe Biden suspended them shortly after taking office. The leases have been a political football field for 40 years.)

Part of it is the geography and climate of the herd’s vast habitat that somehow leads to fewer great long-term fluctuations in numbers. Part of it is that, except for the Dempster Highway — the road that stretches 740 kilometres from Dawson City, Yukon, to Inuvik, N.W.T. — there’s little to interrupt caribou migration.

But it’s also how the herd is managed. “It’s certainly a model. It should be an inspiration,” says Catherine Gagnon, an independent caribou researcher and post-doctoral student at the University of Quebec, Rimouski.

Since 1985, the herd has had the advice of the Porcupine Caribou Management Board, with representation from five Indigenous groups plus the federal and territorial governments. Joe Tetlichi, the board’s chair, says the board watched carefully as herds in other parts of Canada started faltering. George River. Bathurst.

So, long before their own herd was in trouble, Tetlichi and his board launched a harvest summit to discuss the issues with the communities.

Tenderly, over years, the communities hammered out a blueprint describing how they will alter their hunting practices if the herd’s numbers start to fall. It’s based on a fire risk chart: green, yellow, orange, red. Green means the herd’s numbers are strong and people can hunt however they want. Red means the herd’s down to 45,000 and the harvest has to stop. Today, the herd is green.

“Partnership really is the key to our success,” says Tetlichi. “We don’t fight with other parties. We walk together.”

And they want the caribou to survive. Even as he speaks, he is tuned into the ageless rhythms of the Porcupine herd. The females are pregnant already, and most of the herd is three-quarters of the way to the refuge, he says. They’ll arrive by the first week of June, as they always do, and they will give birth in the first few days of that month, as they always do.

Tetlichi stops there, immersed in his imagination in the vision of all those caribou on the calving grounds, keeping the herd going. But that’s not the end of the story. Tradition says that by summer, with the new calves in tow, they’ll spread out further into the coastal plain and maybe head east, following the plants that sustain them until the autumn’s snowstorms arrive. And that’s when they make the great journey back south to their winter home, as they always do.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the September/October 2021 Issue

Wildlife

The failure to recognize distinct species and subspecies of caribou is hampering efforts to conserve them. So, I revised their taxonomy.

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

Wildlife

Caribou numbers in Canada are dropping drastically — and quickly — leaving the iconic land mammal on the brink of extinction