Environment

The truth about carbon capture

Carbon capture is big business, but its challenges fly in the face of the need to lower emissions. Can we square the circle on this technological Wild West?

- 5042 words

- 21 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Today, cities account for more than 60 per cent of global energy use, and it’s estimated that by 2040, that number will rise to 80 per cent. By understanding how urban development takes place and the stresses it puts on resource systems, we can make informed decisions on how to build more sustainable communities. That’s the goal of Shell’s scenarios on cities headed by Jeremy Bentham, Vice-President of Global Business Environment and head of the Shell Scenarios team. Here, Bentham discusses the project and how Canadian cities can become more sustainable.

How did Shell’s Future Cities project come about and what is its goal?

Cities are hubs for culture, education, communication, livelihoods and finance; it’s no wonder that cities are also centres for energy. Cities occupy less than two per cent of the world’s landmass, yet they’re responsible for around two-thirds of global energy use, and this is expected to rise to four-fifths by 2040. This is why cities have been a significant focus of attention in our Shell Scenarios work, which explores plausible alternative visions of the future to help Shell leaders, as well as governments, academia and businesses, to understand the possibilities and uncertainties ahead. In 2014, Shell published “New Lenses on Future Cities,” a report that looked at 500 cities around the world to explore how individual jurisdictions could evolve more sustainably.

Over the past two years, Shell explored urban development pressures in even greater depth, conducting cities scenarios with municipalities and key stakeholders in two cities — Surat in India and Marikina in the Philippines. It is through understanding cities better that we are also better able to understand resilience, sustainability and energy challenges.

What role do energy companies such as Shell have in creating sustainable cities?

In 2014, 54 per cent of the world’s 7.4 billion people lived in cities, according to the United Nations. By the middle of the century, it’s expected that around 66 per cent of the global population of around 9.7 billion will be city dwellers. This is expected to stress vital resources such as water, food and energy. Energy companies such as Shell have a role in helping deliver more, and cleaner, energy to cities, as well as providing solutions for improvements to energy efficiency. Responding to the development and environmental pressures across the world means understanding how the whole economy uses energy in the built environment, for mobility and in industry. This means understanding more than the narrowly-defined energy system. We need to recognize how industrial activity, energy needs, water systems and urban demands all interact.

In British Columbia, for instance, we have partnered with the city of Dawson Creek on a reclaimed water facility that reduces environmental stress and serves municipal needs, such as watering playing fields, as well as some industrial needs for gas production. This example also highlights the significance of being able to develop collaborative solutions and partnerships that cross traditional industry-sector and public-private boundaries to meet the needs of those involved.

Another important aspect of cleaner energy systems of the future is carbon capture and storage, or CCS. Canadian CCS projects, such as Quest near Edmonton, remove unwanted carbon dioxide from the emissions of industry and power generation and store it safely underground. In its first year of operation, Quest captured and safely stored one million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Why is now the time to start building sustainability within cities?

In 1950, 30 per cent of the world’s population was urban. Cities now host more than half of the world’s population, and this is expected to grow to around two-thirds of world population by 2050 because of the productivity, efficiency and creative advantages that emerge when people come together to live and work.

Naturally, growing populations and growing prosperity increase demand on resources. Energy, water and food are our most vital resources, sustaining life itself and fueling our cities. They comprise a tightly intertwined network: nearly all forms of energy production require water. Energy is also needed to move and treat water, and producing food requires both energy and water.

According the United Nations and Shell, by 2030, the world will need 30 per cent more water, 40 per cent more energy and 50 per cent more food to keep up with rising demand. The world will need to provide that additional energy, water and food in ways that significantly reduce carbon dioxide emissions. As cities become the epicentres for development and industry, how they develop will significantly determine how successfully resource needs are managed. And because urban infrastructures have very long lifespans, the steps taken now are already shaping quality of life for many decades, and even centuries, to come.

What are some of the ways a city can become more sustainable?

The “New Lenses on Future Cities” report, published in partnership with Singapore’s Centre for Liveable Cities, identifies a number of ways to make cities more sustainable. First, urban planning should focus on the efficient use of resources. The design and layout of a city has a powerful impact on its resource needs. Compact, more densely populated cities, such as Hong Kong, use significantly less energy per person than sprawling cities, such as Los Angeles. Why? Partly because people live closer to where they shop, work and play, therefore using less energy to get around.

The use of smaller cars powered by electricity or hydrogen fuel cells, as well as trucks fuelled by liquefied natural gas can also help. Cleaner-burning fuels can improve air quality — a major health consideration in urban settings. Integrating water, sewer, waste and power systems more effectively could allow the water and energy they consume to be recycled. Switching coal-fired power stations to cleaner-burning natural gas would reduce carbon emissions and improve the quality of air in cities.

Truly sustainable urban development is not easy, but it can be done. There are not any one-size-fits-all development plans. All cities are different and come with different challenges. That is why collaboration between government, business and civil society is important. Leaders need to be forward-looking, transparent, flexible and informed by a clearly expressed vision. It is only through collaboration that cities can become the healthy, liveable and competitive hubs they need to be.

What are the six major city archetypes as identified by Shell?

Our research studied more than 500 cities across the world with more than 750,000 inhabitants, including 21 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants, from which we identified six illustrative archetypes to help frame our understanding of energy use in cities. Of course, each is a simplification and, in reality, a single city can exhibit some of the characteristics of multiple archetypes.

In this scheme, Vancouver is a “prosperous community,” with Toronto and Montreal categorized as “sprawling metropolises.” Six Canadian cities were large enough to feature in our global study, but the less populous cities in Canada will generally also reflect the characteristics described for prosperous communities at this stage of their development. Energy use is currently concentrated in two of these city archetypes: sprawling metropolises and prosperous communities, as would be expected from their relative wealth. The way cities continue to develop and how this growth is managed will be important if the world is to move into a low-carbon future. Due to the long operating life of urban infrastructure, the decisions made now will determine how efficiently resources are used and how liveable these cities will be for decades to come.

What specific challenges do Canadian cities face in making the shift toward a more sustainable future?

A major challenge for sprawling metropolises, such as Toronto and Montreal, is higher per capita energy use on buildings and transportation. Annual car travel per person within more compact cities is on average 2,000 kilometres less compared to low-density development. Dense urban dwellings offer shared efficiencies, such as heating, water and waste management. Since buildings and vehicles last several decades in terms of economic life, making the shift to more efficient platforms will take many years and significant amounts of investment.

This year is Canada’s sesquicentennial. How have Canadian cities evolved over the past 150 years in terms of sustainability?

Canadian cities were largely developed around early resource trade and, later, the Canadian Pacific Railway — the first transportation corridor to connect the East to the West. Not only did the railway open Canada up to the global economy, but it also provided opportunity for population diversification across the country for the first time. Canada is a vast landscape with a relatively small population, which gives rise to unique transportation and urbanization challenges that have affected the design of its cities. According to the Conference Board of Canada, on a per capita basis, Canada is one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters in the world. In part, this is due to Canada’s geography as it requires significant energy to transport people and goods across the vast country and to heat buildings through the cold winters.

Fortunately, with the right policy support and collaboration, some aspects of city life can be made less carbon intensive. Short-distance travel could become less carbon intensive through the promotion and adoption of electric and hydrogen vehicles, for example. However, other aspects of city transport, especially those that require longer range travel and the carriage of heavy goods will likely still need to be powered by liquid fuels in the near to medium term. Public transport infrastructures can play a huge role in boosting efficiency. These shifts will take some time though, since the current stock of vehicles on the road will take around a decade before the end of their useful lives and even longer for other vehicles, such as trucks.

Cities also have a huge opportunity to become more energy efficient through building standards, by using waste heat from power generation to warm homes, and by encouraging high-density living to reduce travel.

How can the average person help in making their city more sustainable?

The journey of a thousand miles does start with the first step. Consumers can make choices to better insulate their homes, use public transportation, carpool or drive more efficient vehicles. In the case of driving, the single most effective source of efficiency is not the car itself nor the fuel or lubricant used — it’s the driver.

Even shifts in our diet can have a big impact as the overall water and energy needs associated with high-end foods, such as meat, are massively higher than vegetarian options. Citizens can recognize and place more value on collective funding of investments in developments that support resource-efficient, low-emission compact cities. These include the development of integrated water, waste, power and heat infrastructures, for example. In the future, compact mixed-economy zones could be developed in cities where people live relatively close to their jobs and where infrastructure is easier and cheaper to integrate. Everyone can participate in developing a better life with a healthy planet.

This article was created and published with the financial support of Shell Canada Limited.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

Carbon capture is big business, but its challenges fly in the face of the need to lower emissions. Can we square the circle on this technological Wild West?

Mapping

Six urban planning experts share their views on municipal actions during COVID-19

Mapping

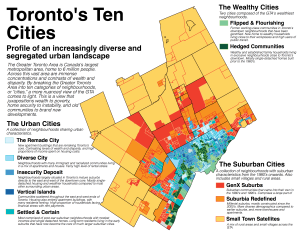

Urban geographer Liam McGuire on how he used maps to illustrate growing inequalities in Canadian cities

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)