Environment

The sixth extinction

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

- 4895 words

- 20 minutes

Environment

Collaborative research is uncovering the secrets of coastal seagrass beds to help keep them healthy

What do knee-high pantyhose have in common with fertilizer used on garden tomatoes? Believe it or not, they are both used in conservation research on a very important coastal habitat in Canada that most people have never heard of: seagrass beds.

Studying and saving this important habitat requires me to be out at midnight in Boundary Bay, just south of Vancouver, and the damp coastal night has me chilled to the bone. My headlamp lights up three other scientists in waders squelching through the sand and knee-high seawater. With all our measuring tapes, vials, and collection bags, you could be forgiven for thinking we’re investigating a crime scene. But in fact, we’re here to measure the biodiversity of species living in the seagrass bed and how water pollution causes loss in these important habitats.

Seagrass beds are kind of like prairie grasslands or alpine meadows, except they’re underwater! Found in sandy or muddy coastal areas, seagrass beds are filled with bright green, ribbon-like grasses that wave gently in the calm, shallow water. If you’ve ever been kayaking or paddle boarding, you’ve probably floated right over one.

The similarities between a seagrass bed and a meadow on land are numerous. Instead of bees, butterflies, and other insects, seagrass harbours a diversity of marine invertebrate organisms. Many of the invertebrates living in seagrass beds are like land insects, but there are also abundant species of mollusks (snails, clams, mussels), worms, and echinoderms (urchins and seastars).

Fish swim through seagrass plants, which can grow to over two metres high, and shorebirds dive into these meadows for food. These underwater meadows are found along coasts all around the world, including all three coasts in Canada. Some of our favourite seafood, such as salmon, herring, and crabs, depend on seagrass beds for their hunting and habitat.

Scientists don’t yet have a complete map of everywhere seagrasses are found in Canada, but they are abundant on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Like all plants, seagrass needs sunlight to photosynthesize, and ecologists originally thought it wouldn’t fare very well in the long, dark Arctic winters, but seagrass beds have been found as far north as Baffin Island in Nunavut. Everywhere they’re found, seagrass meadows are incredibly important to coastal ecosystems and human communities.

By now you’re probably wondering where the pantyhose and fertilizer come in. Like all plants, seagrass needs nutrients to grow, but too much can be a bad thing. Chemical runoff from agriculture and other human development can cause algae to bloom and the seagrass to die, which in turn harms the many creatures that depend on seagrass.

Myself and a diverse group of collaborators, including The City of Surrey, Ducks Unlimited Canada, the Friends of Semiahmoo Bay Society, the University of British Columbia and others from the local community, have partnered to understand how nutrient pollution might harm seagrass. We’re focusing our efforts on Boundary Bay because it’s the largest seagrass meadow in Canada’s Pacific region and is internationally recognized as an important estuary for migratory birds due to its location on the Pacific Flyway. More than 1.5 million birds visit Boundary Bay in the fall and spring. Some ducks and geese eat the seagrass itself, while other birds search for algae and invertebrates living in the seagrass to fuel up for their migratory journey.

Ecology experiments with garden fertilizer tied into the foot of a nylon stocking are used in marine ecosystems around the world to understand how human-caused nutrient enrichment can upset the delicate balance of species interacting in these environments. It’s an old trick of the trade, passed down to me by my PhD advisor Peggy Fong and taught to her by influential restoration ecologist Joy Zedler.

The nylon-enclosed fertilizer is anchored within the seagrass habitat. The nutrients contained in the fertilizer show us what is likely to happen if too many nutrients flow into a seagrass bed. Once a month, we return at low tide, often in the middle of the night, to collect samples from the meadow. The great thing about our experiment is that the fertilizer only works on a small area and doesn’t have any lasting impacts. This is not true when large amounts of nutrients flow into coastal environments from human development and agriculture.

Back in the lab, the samples collected from Boundary Bay are processed by a team of scientists, secondary school students, and undergraduates. Seagrass, algae, and animals are separated from each other and counted. After the invertebrates are removed from the plants and mud, a highly trained entomologist, Dr. Felipe Amadeo, uses a powerful microscope to identify each species.

Through this work, we’ve been able to discover just how many invertebrate species live in Boundary Bay. An area the size of your laptop can be home to over 40 different species and 4,000 individual invertebrates! Even though most of us will never see these invertebrates, they are very important links in the food chain. Take the shrimp-like amphipod, only five millimetres long, that pollinates seagrass flowers, much like bumblebees in your home garden. Or the isopod that sticks to a blade of seagrass and roams around to eat tiny algae. Both are important diet items for commercially valuable fish like the herring and juvenile salmon.

All this information is being used to establish water quality criteria, research plans, and regular monitoring protocols to protect the incredible biodiversity of Boundary Bay.

All people living on the coasts of Canada have a close relationship with seagrasses, even if it’s not immediately apparent. Indigenous Peoples in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic regions have used seagrasses for food and materials for millennia. The sweet rhizomes of seagrasses are steamed to flavour meats and can be dried for winter food. Herring and other fish are also known to spawn within seagrass meadows and the eggs are harvested and eaten with seagrass.

Besides their role as habitat for important food fish, seagrass meadows protect our coasts from high-energy waves from the ocean. This protection is especially important during storms; without it our coastal towns and cities would not exist. Large seagrass meadows also absorb carbon though photosynthesis and store it in their tissues, which can help slow climate change. We certainly owe a lot to these meadows of the sea.

The Boundary Bay collaboration provides an example of necessary community engaged conservation where diverse stakeholders are working to protect seagrass habitat through research and management. It makes the freezing nights in the seagrass meadow at low tide well worth it.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Wildlife

An estimated annual $175-billion business, the illegal trade in wildlife is the world’s fourth-largest criminal enterprise. It stands to radically alter the animal kingdom.

Environment

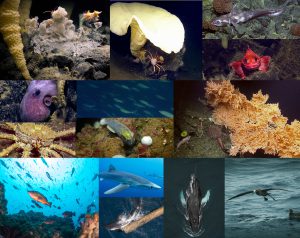

Two marine biologists offer a glimpse of life at the bottom of the ocean during 2018, 2019 and 2020 seamount expeditions

Environment

A new study finds zoos and aquariums in Canada are publishing more peer-reviewed research, but there is still more to be done