Environment

The promise of COP15

Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault made big commitments at the international biodiversity conference held in Montreal in December. What does that mean on the ground?

- 2316 words

- 10 minutes

Environment

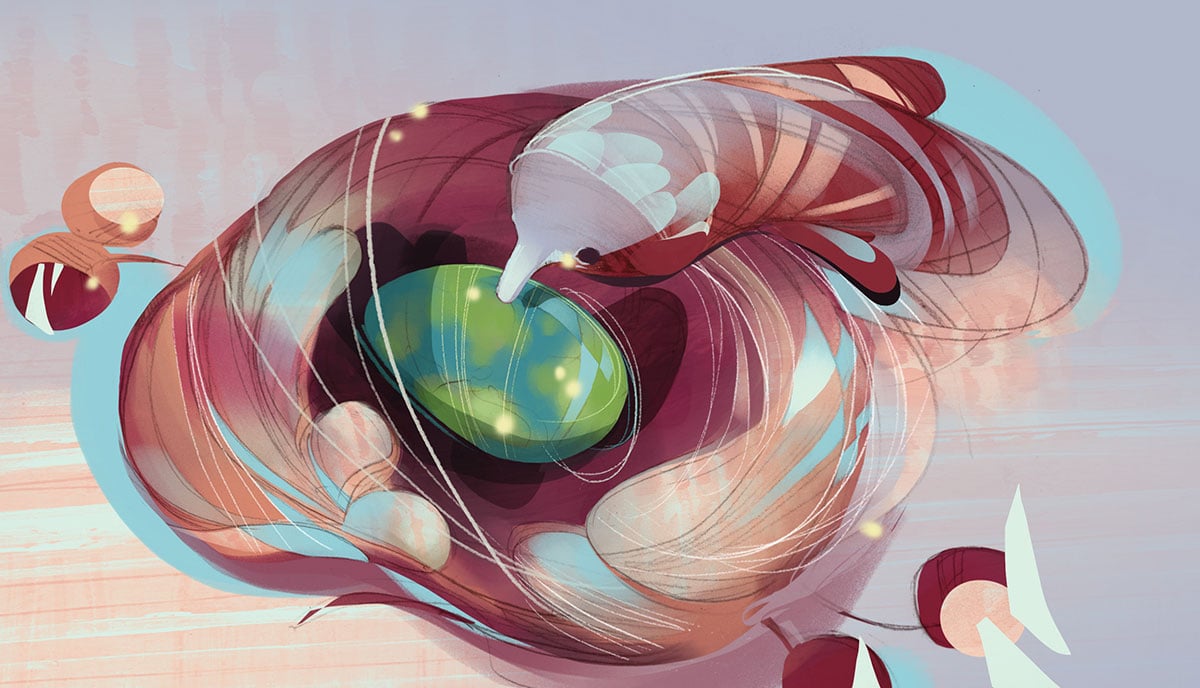

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

“It seems to me that if you wait until the frogs and toads have croaked their last to take some action, you’ve missed the point.”

—Kermit the Frog

An eclectic dinner group gathered during a symposium called Thinking Extinction at Laurentian University, in Sudbury, Ont., seven years ago. Philosophers had joined leading biologists to address approaches — from captive breeding to the ethics of reviving long-extinct species to practising medical-style conservation triage — to the growing global biodiversity crisis.

“Bringing humanities into a typically scientific discussion recognizes that all of us face questions about our role in protecting species diversity,” said Albrecht Schulte-Hostedde, co-organizer and Canada Research Chair in applied evolutionary ecology. “We hope it adds new dimensions to the conversation.”

If table talk was any evidence, it had. Renowned turtle researcher and Laurentian professor Jacqueline Litzgus was expressing frustration at a bugbear query inevitably posed by the public, industry and media: Why should we care? “I just don’t want to answer,” she lamented. “If that’s the question when we’re talking about saving a species from extinction, we’ve already failed.”

Litzgus and Stuart Pimm, professor of conservation ecology at North Carolina’s Duke University, were discussing the lack of public buy-in for saving animals other than charismatic critters such as lions, tigers and bears. In reply, Pimm floated the moral imperative to not allow any species to go extinct — and that because politicians, rather than qualified professionals, often decide which ones to protect, people should be universally concerned. But it was author Margaret Atwood who talked Litzgus off the ledge.

Leaning over the table, Atwood wrapped the scientist’s hands in the deft fingers that have delivered countless literary treasures. “My dear you’re going about it all wrong,” she said quietly, “You think you have to tell people why they should care from a human perspective, but you should really be telling them why to care from the turtle’s perspective.”

A moment of silence ensued.

All gathered grasped Atwood’s abstraction for the clever reverse-engineering it represented: you need to understand the impact of species loss on nature, to see how it impacts us all.

In late February 2020, as the world was just beginning to grapple with COVID-19, delegates from more than 140 countries gathered at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in Rome. They were there to discuss a key document in the lead-up to the 15th meeting of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (then scheduled for October 2020 in Kunming, China, but now postponed).

Known as COP15, the meeting in China will be the largest global biodiversity gathering in a decade — a period of serial disappointments on the wildlife conservation front. So, expectations are high, with a desire to officially approve targets largely agreed to beforehand. The first step in this process was refining in Rome a framework (produced by a Canadian and Ugandan co-chaired working group) that featured five long-term goals for 2050, with intermediary milestones and targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, including proposals to protect a third of the world’s oceans and land and cut pollution from plastic waste and excess nutrients in half.

The Rome proceedings were both auspicious and steeped in irony. At the last minute, they had been moved from China over coronavirus fears (less than a month later, COP15 itself would be postponed until 2021 for the same reason), and, as delegates spun their spaghetti in the capital, Italy’s north was struggling to contain an ultimately devastating outbreak of COVID-19. With a direct link between the environmental breakdown behind biodiversity loss and the emergence of zoonotic diseases (those that jump from animals to humans) laid bare by the suspected acceleration of the coronavirus’s spread from a wildlife market in Wuhan, China, dialogue on the draft document was suffused with added urgency.

China quickly shuttered the Wuhan market and issued a temporary ban on others. But this ultimately raised a much larger question: would people finally take the destruction of nature more seriously in the wake of such a dire global consequence? No less an environmental luminary than Jane Goodall opined that humanity is “finished” if we fail, post-COVID-19, to adapt our food systems away from over exploitation and deforestation.

Given subsequent actions, however, those prospects look bleak. Amid pandemic isolation and race-related civil unrest, and having already rolled back 100 environmental regulations for air, water, land, wildlife and health, American President Donald Trump’s administration removed longstanding protections for wild birds and eliminated nearly 85 per cent of marine protected areas along the continental United States. In Canada like-minded conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario suspended environmental compliance and reporting for industry or extended existing exemptions. Elsewhere in the world, wildlife poaching skyrocketed and forests were illegally levelled.

This grim track record mirrors humanity’s collective response to other large-scale existential threats. In the same way that catastrophic climate events haven’t galvanized action on reducing atmospheric carbon, the accumulating hallmarks of soaring biodiversity losses have not inspired us to flatten that curve: not the repeated bleaching of the world’s coral reefs; not the visible-from-space slashing and burning of Amazon rainforest (responsible for a third of old-growth tropical forest loss — of some 3.8 million hectares, close to the size of Switzerland, in 2019); not the northern white rhino blinking out of existence; and not Singapore’s seizure of US $48.6 million in trafficked elephant ivory and pangolin scales. Worse, the much-ballyhooed Convention on Biodiversity, born from the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, has been similarly unable to move the needle — even a bit.

Despite some local successes, an international global biodiversity pact committed to in 2002 did not reduce the overall rate of decline. By COP 10 in 2010 in Nagoya, Japan, the 193 signatories of the Convention on Biodiversity deemed it a de facto failure in need of a reboot. That effort, which yielded 20 so-called Aichi biodiversity targets (Aichi being the Japanese prefecture that includes Nagoya) aiming to achieve five broad goals under the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, is also on track to come up short. Hence that more ambitious prescription being readied for COP 15. But having lost another decade (and thousands more species) and now suffering a related and costly pandemic, where is global biodiversity governance headed? And what is Canada doing to halt its own biodiversity slide?

We’re in the midst of a planetary sixth extinction. The present episode has only one root cause: Homo sapiens.

There is no better snapshot of biodiversity woes than the landmark 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, known as IPBES. The work of hundreds of scientists who reviewed data from more than 15,000 sources, the report highlights humanity’s crucial reliance on nature for food, water, medicines, energy, livelihoods, and cultural and spiritual fulfilment. It also shows this same dependence eroding nature, with species rapidly declining in both range and number. (An example: despite the loss of a quarter of North American bird fauna since 1970 — an estimated three billion animals — industry continues to kill hundreds of millions of birds annually.) And essential services provided by ecosystems — water filtration, carbon storage, seed dispersal, pollination — are also breaking down. Having “severely altered” three-quarters of the planet’s land surface, humanity has put one million species at risk of extinction.

This eye-opening number corroborates that we’re in the midst of a planetary sixth mass extinction. The previous five, spread over a half-billion years of geological time, accrued from combined natural causes — cataclysmic meteor strikes, volcanism and atmospheric shifts. The present episode has only one root cause: Homo sapiens.

The study reported a normal extinction rate for vertebrates as two species lost per 10,000 per 100 years — or 0.1 per cent over 500 years. A conservative estimate of recent extinction rates during a similar time span, beginning in the year 1500, shows mammals at two per cent, and birds, reptiles, amphibians and fishes at about 1.5 per cent.

Focusing on species extinctions, however, distracts from equally worrisome trends in population declines and extirpations (local disappearance). The World Wildlife Fund’s living planet index shows a staggering 60 per cent decline in wildlife populations in just 40 years. Freshwater fish had the highest extinction rate worldwide among vertebrates in the 20th century, but a 2017 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found a third of 27,600 terrestrial vertebrate species are undergoing worrisome population loss — even common species of supposed “low concern.” The authors suggested as many as half of the animals we once shared the planet with have vanished, a “biological annihilation” in need of urgent redress. Three years later, in June 2020, these same authors’ cri de coeur rang louder after finding the extinction rate to be accelerating: some 543 terrestrial vertebrate species had disappeared during the past century and 500 more could follow in the next two decades — a combined loss equivalent to what would naturally occur in a 16,000-year period.

The ocean is also under siege. IPBES reported overfishing and bycatch severely affected biodiversity in two-thirds of marine environments. Since the early 1970s, five large shark species found along the eastern U.S. have declined by 97 to 99 per cent each, and a quarter of the world’s sharks and rays are now threatened. A 2020 University of British Columbia study found climate-driven ocean warming and acidification were affecting glass sponge reefs unique to the Pacific northwest that had also seen damage by bottom trawlers and salmon farms. And the complex ecosystems of tropical coral reefs are suffering huge biodiversity losses.

Despite its large size, vast spaces and relatively low population, Canada hasn’t been immune to such impacts. According to the 2017 WWF Living Planet Report Canada, 451 of 903 vertebrate species monitored in this country declined by an average 83 per cent between 1970 and 2014. Since Canada passed its Species at Risk Act in 2002, 154 threatened populations have continued to decline by an average 2.7 per cent annually (compared to declines of 1.7 per cent annually in the 30 years prior). Habitat degradation is responsible for about half of losses in birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish. Only in mammals is habitat eclipsed by the second largest threat — invasive species and disease. Pollution, climate change and exploitation affect all groups to similar extents.

In its 2019 report, IPBES noted how conservation goals for 2030 and beyond will be possible only through transformative changes across all sectors of society. One of those transformations is money.

Unsurprisingly, we’re already paying for biodiversity loss — a US $10-trillion hit to the world economy by 2050 under a “business-as-usual” scenario according to a January 2020 WWF report. It follows that spending far less to reverse this trend would be a sound investment; indeed, the study calculates a US $490 billion annual net gain in GDP under a “global conservation” scenario.

Money is the critical determinant in achieving biodiversity goals, yet governments remain reticent to fund things with uncertain outcomes — despite data suggesting success. A model published in the journal Nature in 2017 shows how conservation spending during 12 years reduced biodiversity loss by almost a third in 100 signatory countries to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Indeed, back in 2013 at the Thinking Extinction symposium, Bridget Stutchbury, a biology prof at Toronto’s York University, noted the average cost of improving the status of a single endangered bird species was about $1 million per year. “If open heart surgery costs $75 billion a year, the U.S. defence budget is $1.8 billion per day, and the world sees $470 billion in annual soft drink sales, there’s plenty of money in the system,” she said. “If every taxpayer in North America gave $10 each year, we could probably save everything [in North America].”

Stutchbury wasn’t far off. Though the costs for meeting the 2010 Aichi targets are largely unknown, reducing extinction risk for all globally threatened bird species was priced at US $875 million to $1.23 billion annually over the next decade in a study published in the journal Science; when other threatened species groups were added, the cost tripled. Estimates for protecting and managing all terrestrial sites of global conservation significance ranged from US $65.1 billion to $76.1 billion annually. So, meeting Aichi targets — or the more ambitious ones likely to replace them — will require worldwide conservation funding to increase by at least an order of magnitude.

Recognition of this need is reflected in a recent European Union pledge to raise 20 billion euros a year to boost biodiversity. Can the rest of the global community afford to do this? Can it afford not to?

Most Canadians want to protect endangered species. But their commitment to the cause slips if that means limiting industrial development or private property rights.

A 2017 Canadian study that assessed public commitment to endangered species protection found that 89 per cent of Canadians were, in principle, strongly in favour. After adding the caveat of limiting industrial development, 80 per cent remained supportive. But only 63 per cent stayed on board if efforts limited private property rights, and this share fell further for scenarios involving the outright loss of jobs or property rights such as constructing new buildings or creating trails. This lower tolerance for personal impacts in preventing species extinctions explains the difficulty of prioritizing conservation over socio economic forces. It also explains the range of programs in Canada encouraging public private partnerships, a reflection of the “stewardship first” ethos baked into the Species at Risk Act — strong regulations to protect species are imposed solely on federal lands, with voluntary stewardship relied on for private lands.

In response to the Aichi targets, in 2015 federal, provincial and territorial governments collaborated on biodiversity goals and targets for Canada for 2020. The document reflects both Canadian priorities and ways to aid the global effort. (Canada, for example, holds a quarter of the world’s wetlands, the majority in the boreal forest; these are important not just for their inhabitants but also for species that migrate through them.) Canada’s 19 targets support four goals: A) better land use planning and management; B) more environmentally sustainable management across the economy; C) improvements to available information concerning “people benefits” of nature; and D) increased general awareness of biodiversity and participation in conservation.

Progress on these goals was recently reviewed in Canada’s 6th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. The news was typically Canadian: not great, but not horrible, with a dose of overoptimism.

Working backward, goal D’s two awareness targets are on track, which should help drive future targets faster. Surprisingly, three of four targets under goal C’s low hanging fruit of public outreach are lagging. The only winner? Integrating the capital value of natural systems into Canada’s statistical tracking system. Better, of eight targets under goal B, we fall short on only two: the sustainable and legal harvesting of fish and aquatic invertebrates, and reducing water pollution. Finally, of the five targets under goal A, three look good, but we lag in whole or in part on the two most important: Target 1, that we conserve 17 per cent of Canada’s terrestrial (land and fresh water) area and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas; and Target 2, that species whose status is secure remain so, while species at risk trend toward recovery. As of 2020, 12.1 per cent of land and 13.8 per cent of marine areas are protected — the latter a positive overshoot on the strength of new Indigenous conservation areas.

“Canada shares the priorities and challenges of having vast regions with Russia, Brazil and Australia,” says Niall O’Dea, assistant deputy minister, at the Canadian Wildlife Service. “It’s an integrative, planning-intensive exercise that interfaces with climate challenges and Indigenous reconciliation, but we’ve developed momentum to achieve the 17 per cent land protection target, move to 25 per cent by 2025, then 30 per cent beyond that.”

With respect to Target 2, though a large proportion of secure wildlife are indeed holding steady, many at-risk species are more at risk than ever, as publicized in desperate gambits such as shooting wolves from helicopters to save caribou in Alberta and B.C., boating and fishing restrictions to stabilize southern resident killer whales whales and their salmon prey on the Pacific coast, and court-involved enforcements of the federal Species at Risk Act for greater sage grouse in Alberta and western chorus frogs in Quebec. The Nature Conservancy and NatureServe Canada released a first compilation of Canada’s endemic species in June 2020 showing that of 308 animals, plants and fungi found here and nowhere else, almost 40 per cent are imperiled — eight are already extinct.

Arne Mooers, a professor of biodiversity at B.C.’s Simon Fraser University, has published widely on global biodiversity issues and participates as a non-governmental scientist on the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, also known by its acronym COSEWIC — the front end of species-at-risk conservation in this country. “We’ve realized for a while we’re not close to achieving Target 2,” he says, “though you might think Canada was well-placed to get there because COSEWIC has been around so long.”

Since 1977, in fact, an outcome of the 40th federal-provincial wildlife conference in Fredericton. As a conservation tool, COSEWIC’s rigorous process — in which at-risk species are independently assessed and recommended for listing under the Species at Risk Act — is highly regarded internationally and much lauded by participants such as Mooers.

“It’s the best, most-satisfying scientific advisory position I’ve ever had,” says John Reynolds, professor of aquatic ecology and conservation at Simon Fraser and current COSEWIC chair. “The government gets a lot of value for very little money — the devoted expertise of 155 volunteer scientists from across the country who are experts on species — either scientifically or in the context of Indigenous knowledge. The vibe at assessment meetings is very positive.”

Rigid adherence to procedural standards makes the committee effective but cumbersome, a proverbial large ship in a tight waterway steered carefully, to the benefit of species at risk, but slowly, with the opposite effect. Nevertheless, COSEWIC assessments move at lightning speed compared to the subsequent formal listing process, where the entire vessel can run aground — as Laurentian’s Jacqueline Litzgus, whose turtle subjects are among the world’s most at-risk group, knows all too well after a 12-year stint on the committee. “COSEWIC is doing all the things it needs to,” she says. “All these busy scientists gather at an amazing consensus-based roundtable, and reports are written by the most knowledgeable experts to get the best results. But then… sometimes nothing.”

As of April 2019, the committee had assessed 799 species, finding 356 endangered, 189 threatened, 232 of special concern and 22 extirpated. Only 580 of these, however, are actually listed, the seven-step process from COSEWIC designation to a ministerial order a bottleneck of capacity issues, socioeconomic pressure and political interference (some pending listing decisions date back 15 years). “The challenge is to get everyone else in the chain of protection to keep up with COSEWIC,” notes Reynolds, “because it’s ultimately cheaper and faster to assess the status of a species than to bring it back from the brink of extinction.”

The bureaucratic snaggle, in part, lies in the incrementalism of one-species-at-a-time recovery strategies and action plans. To cut the Gordian knot, a new kid appeared on the block in 2018 — a pan-Canadian approach to transforming species at risk conservation in Canada. According to its guiding architect Kaaren Lewis, the executive lead for the species at risk program and species transformation for Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Nature Conservation Agenda, the framework will “help shift conservation implementation from the current species-by-species approach to more multi-species and ecosystem-based initiatives. Working with provinces, territories, Indigenous groups and other partners on shared priority species, priority places and priority threats, we’re hoping to see better conservation outcomes for species at risk, increased co-benefits for biodiversity and ecosystems, and improved return on investment.”

To help that along, the pan-Canadian plan comes with $155 million through the species-at-risk stream of the federal Canada Nature Fund to encourage more collaboration and partnerships. “Federal funding helps bring others to the table,” notes Lewis.

“It’s an almost revolutionary departure from business as usual, which makes it both interesting and worth supporting,” says Mooers. “Done right, it could really help with situations where you need buy-in from everyone to prioritize certain species, while recognizing that you can’t do everything equally well everywhere you try.”

Collaborative landscape-level approaches could certainly help in B.C., which lacks dedicated endangered species legislation to support its country-leading 1,807 species of animals and plants at risk of extinction and range of environmental issues: the systematic under-reporting of deep-sea fish trawled from provincial waters because of intimidation and harassment of government observers; the diseases, parasites and waste of non-native Atlantic salmon reared in crowded, open-ocean fish farming pens affecting wild Pacific salmon already hurt by overfishing and degradation of spawning habitat; the wine-soaked Okanagan desert, where virtually everything is endangered; the perennial crashes of woodland and mountain caribou; and poster boy for B.C.’s failure to protect old-growth forests, the spotted owl debacle.

A species listed as endangered since 2003, the spotted owl is now functionally extinct in the province. Not only is a plan for spotted owl recovery 14 years overdue, but the B.C. government approved 312 new clearcuts in the dwindling, highly fragmented old-growth habitat required to reintroduce owls from a captive-breeding program it has funded for years. “It’s disappointing,” wildlife biologist Jared Hobbs told The Narwhal in May. “It’s counterintuitive to the government’s other purported mandate, which is to conserve species at risk and to recover spotted owls.”

As a one-time scientific advisor to the spotted owl recovery team, Hobbs may have been the last person to see this species in the wild in Canada. The current dysfunctional pas de deux results from B.C.’s continued promise to do something — more or less buying time — with the feds avoiding the alternative of forcing the province to protect economically valuable forest habitat using the federal Species at Risk Act.

Not that good things aren’t happening, too — they are, daily, right across the country. Like a successful $825,000 collaboration between universities, butterfly breeders and conservation groups to reintroduce the endangered mottled dusky-wing butterfly to its preferred oak savannah habitats in southwestern Ontario. Or the new Mark Bass Nature Reserve, comprising wetlands important to flood mitigation and at-risk Blanding’s turtles, that adds to a patchwork of set-asides in Ontario’s Prince Edward County totalling 1,000 hectares. There are successful reintroductions to the wild of kit foxes, black-footed ferrets, Vancouver Island marmots, whooping cranes and leopard frogs to shout about. And there’s the delisting of Pacific humpback whales and peregrine falcons — some of the earliest species officially identified as endangered in Canada.

Yet for every wound to nature for which we stanch the bleeding, a new cut — or three — appears. The reality on the ground is even more brutal. “Why isn’t species-at-risk legislation ever mobilized to actually stop something? Why does the economy always trump everything else?” wonders Laurentian’s Litzgus, while sharing stories of graduate students working on highway and energy project construction sites reduced to tears by the destruction of habitat containing literally all of Ontario’s most at-risk reptiles. Both practically and philosophically she’s right. The need to “balance the economy and the environment” we so often hear from politicians is a distracting abstraction, a zero-sum game in which an environmental “win” is really only a reduced degree of loss. With renewed government resolve, serious money and a new conservation framework in hand, things can only improve.

Back in 1995, University of British Columbia fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly introduced the phrase “shifting baseline syndrome” to describe the slow creep of changes to nature that caused fisheries scientists to overlook the past, taking diversity and abundance numbers measured early in their careers to be the “normal” state. The concept had immediate application to all of ecology: failure to account for shifting baselines ensures that population declines and target numbers for recovery are chronic underestimates and that bio-inventories will fail to capture both losses (extirpations) and additions (introduced species). A 2018 review attributed this widespread “generational amnesia” — the cause of our rising tolerance for environmental degradation and lowered perceptions of what’s worth saving — to a chronic lack of knowledge of historical ecological data. Coincidentally, the Green Status, a new species-recovery initiative from the International Union for Conservation of Nature set to launch in January 2021, will complement the organization’s Red List of Threatened Species but focus instead on recovery rather than extinction. It will also incorporate historical data as part of a broader shift toward long-term thinking in conservation biology.

In April, with the pandemic raging globally, Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s acting executive secretary, addressed the issue of wildlife markets. Referencing the new coronavirus and recent outbreaks of Nipah and Ebola viruses, all of which putatively originated in bats, Mrema echoed a growing body of literature that shows how large-scale deforestation, habitat degradation, intensification of agriculture, wildlife trade and global warming combine to drive both biodiversity loss and new diseases. “Two-thirds of emerging diseases now come from wildlife,” she noted, adding that to prevent future pandemics, “countries must ban markets that sell wildlife for human consumption” — while ensuring critical food sources for otherwise dependent communities.

There’s an old adage that you should judge a civilization not on its wealth, but on how it treats its working classes — those most relied on for society’s material gain. The natural world offers a parallel: although it contributes a yeoman’s share to all human progress, we continue to exploit it mercilessly. Nature has no voice to raise in defence, yet when it convulses — as with COVID-19 — we all suffer its outcry. How do we start thinking differently?

On the tail-end of World Biodiversity Week this past spring, the Global Biodiversity Festival, hosted by Ontario-based Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, convened some 65 live virtual event with scientists, explorers, conservationists and policy-makers from more than 20 countries. The online festival drew 25,000 YouTube views and raised $12,000 for six conservation groups. Most presentations banged the drum of more protections, more money and more understanding of biodiversity’s role, but Marco Lambertini,director general of WWF, most clearly summed the actions needed. The need to stabilize climate and biodiversity loss for us to live in harmony with nature should be job one globally, he said. It will require a sea-change in thinking: producing more responsibly, consuming more wisely and building a green economy with subsidies and investment in more sustainable production of food, energy and goods. With $44 trillion of economic value generation — equivalent to half the world’s GDP — dependent on nature according to a report by the World Economic Forum, Lambertini foresees a cultural revolution that puts “the idea that nature is not just beautiful, but indispensable” at the centre of thinking and planning.

“We need a New Deal for nature and people — a ‘Paris moment’ for nature if you will,” he said. “We have an opportunity to do that at COP 15 in 2021.”

There will be big asks there, and perhaps a willingness to answer them given the global events of 2020. In fact, scientists have already demanded that the new COP 15 agreement include an easily understood and measurable target comparable to the limit of 2 C warming baked into the Paris climate agreement: to prevent long-term negative impacts on the environment, they argue, species extinctions should not exceed 10 times the background rate — that is, the rate if humans weren’t around. With about two million species now described, this corresponds to limiting global extinctions to fewer than 20 organisms per year.

Whatever concessions are made in delivering a clear political target for species conservation, however, scientists see only one way forward: adopting a carbon neutral and nature-positive world with the participation not just of governments but each of 7.8 billion people. So far, even a direct threat to human existence seems but a fleeting and fractious call to action. But maybe there’s a simpler way to get everyone on board. And it isn’t a new idea.

“We can’t save what we don’t love” is a sentiment widely touted in biodiversity circles, one that ultimately informed Margaret Atwood’s long-ago answer to Jacqueline Litzgus’s dinner party handwringing over why we should care. “You must tell people to simply love turtles, my dear,” the author said wryly, “the way they love us — unconditionally.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the September/October 2020 Issue

Environment

Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault made big commitments at the international biodiversity conference held in Montreal in December. What does that mean on the ground?

Environment

David Boyd, a Canadian environmental lawyer and UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, reveals how recognizing the human right to a healthy environment can spur positive action for the planet

Environment

Representatives from 196 countries will meet in December to create a plan to save the planet’s dwindling biodiversity

Environment

As the impacts of global warming become increasingly evident, the connections to biodiversity loss are hard to ignore. Can this fall’s two key international climate conferences point us to a nature-positive future?