Kids

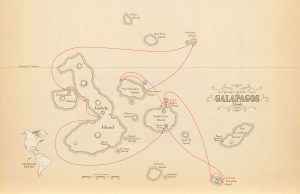

Giant floor maps put students on the map

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

- 1487 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Kids

Shortly after Judith Adler made a basic map quiz part of her second-year Sociology of the Family class at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s, she realized that her students’ knowledge of the world map wasn’t basic at all — it was terrible.

Some couldn’t identify Africa. Others confused the Antarctic with the Arctic. And many mislabelled the Atlantic Ocean — the very body of water whose salty breezes waft over the city in which they live.

The story of the students’ poor quiz scores made headlines in January and caused many to express concern about the state of education in Canada. “I’m not interested in specialized knowledge,” says Adler. “But I realized that other kinds of learning can’t take place without a certain kind of foundation, and I discovered that foundation wasn’t there.”

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the home province of about 80 percent of Memorial’s students, children are expected to learn the continents and provinces in grades 3 to 6. There are no mandatory geography courses in grades 7 to 12.

The situation is similar across Canada. In most provinces and territories, there has been a move away from geography- specific courses toward a more general social studies program. (Only Ontario has a mandatory high school geography-specific course.)

Peggy March, the Atlantic representative of the Canadian Geographic Education executive, believes this has affected the quality of geographic education. “When you generalize many disciplines that relate to the social studies,” she says, “some things get prioritized and some get left out. It boils down to the teacher’s choices.”

A 2010 report published by Dickson Mansfield, former adjunct professor with the faculty of education at Queen’s University, in Kingston, Ont., and graduate student Allison Segeren comparing geography courses nationally from 1991 to 2010 suggests that all provinces and territories have deemphasized geography at the grade seven and eight levels. Fewer geography-specific high school courses were offered in 2010 than in 1991, although there were more social studies courses.

How people perceive geography could be part of the problem. “There’s been a longstanding misperception about what geography actually is, and I think that’s a big part of our battle,” says Anne Smith, an instructor in the faculty of education at Queen’s University. “People think that it’s about labelling countries and capitals, and some say that’s not important to know. You have to have a background in that, but it’s not the meat of the subject.”

Adler agrees. “I’d be willing to let students learn the capitals of places on a needto- know basis,” she says. “But there’s some foundational learning, a sense of basic pattern, that has to be stored in our minds. Without that, the students will not have any coherent image of the ‘whole world.’ And it’s a ‘whole world’ that one generation must pass on to the next. I think that’s what’s being denied.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

Mapping

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.

Mapping

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps

Mapping

If you’ve ever had to help make a map, it gives you a whole new appreciation for the art form. As editor of Canadian Geographic, I’ve found myself more…