Travel

Trans Canada Trail celebrates 30 years of connecting Canadians

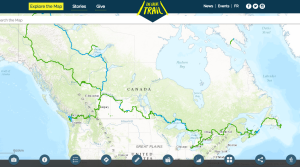

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

- 1730 words

- 7 minutes

Travel

Cities and towns along the Fundy Trail Parkway are banding together to prioritize community and the environment as they share their magical landscape with the world

It’s pouring rain on the Fundy Trail Parkway, a jaw-dropping scenic drive that starts just east of the seaside town of St. Martins and hugs the Bay of Fundy coast through Fundy National Park. My husband and I pull into the trail-head parking lot, our two kids in the back seat, and try to decide whether to wait out the rain or go for it and get soaked. Fifteen minutes later, the rain stops and the clouds thin. We gear up, putting our four-month-old and almost three-year-old in their carriers. Half an hour later, we’re standing on the edge of a small waterfall, the roar of rushing water in our ears, field mice skittering between verdant green ferns at our feet.

The Bay of Fundy has always felt magical to me. My older sister started taking me hiking and camping here when I was a kid. I remember forests glowing green with bright moss, cool air tinged with the metallic scent of fog and stars so bright they looked like crystals in the ink black sky. We took Ewan on his first backpacking trip here when he was 10 months old. We slept on the beach and woke up before dawn to watch the sun rise over the bay.

But I’m not the only one who loves it here. The Upper Bay of Fundy region is an increasingly popular destination, with an influx of about 250,000 visitors during the peak summer season. People from all over the world flock here for the towering cliffs, the abundant wildlife and, of course, the highest tides in the world. In the town of Alma, where ocean tides can reach 13 metres, you can see fishing boats floating in the water at high tide and then spot them sitting on the ocean floor six hours later.

While residents in the Rural Upper Bay of Fundy region take pride in showing off their home to the world, the visitors bring a host of challenges for local communities. Oftentimes, day-trippers show less-than-optimal consideration for the towns along the way as they hop on the 30-kilometre-long scenic route that is the Fundy Trail Parkway, passing through on their way to the big attractions like Hopewell Rocks, the St. Martins sea caves and Fundy National Park. “When we asked people how tourism makes your community better — do you have better parks, better trails? — the results were mixed,” says Micha Fardy, executive director of the charity Friends of Fundy.

That’s why, in 2020, a group of local leaders started hatching a plan to build a locally led regenerative tourism strategy. In a nutshell, regenerative tourism prioritizes community and the environment. The idea is that as communities develop events and infrastructure, they ensure each piece of the tourism puzzle is rooted in celebrating local culture and growing local economies in a healthy way. Inspired by sustainably developed destinations like Fogo Island in Newfoundland, the goal of the Rural Upper Bay of Fundy Destination Development Project is to link rural communities with each other — and put the health of these communities and the environment first.

While a regenerative tourism model is, by its nature, resolutely local, the partnership also draws on expertise from Trans Canada Trail and Destination Canada, a federal tourism entity, as well as funding and expertise from the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency and Tourism New Brunswick.

“We’re sitting on a bit of a gold mine. We’ve got an embarrassment of riches — the natural beauty in this area,” says Jason Thorne, community services director for the town of Sussex. “We need to develop tourism and the economy in a way that doesn’t jeopardize the future liveability of this region.”

The rural upper bay of Fundy region comprises salt marshes and dykelands, ancient cliffs, fossilized sand dunes, rolling forested hills and the longest stretch of wilderness coastline on the eastern seaboard. It’s an ecological zone, not a jurisdictional one, running from the town of Hillsborough in the east to St. Martins in the west and Sussex to the north. It’s also home to 15,700 people, one national park, three provincial parks, a UNESCO biosphere reserve and a UNESCO global geopark.

The parkway, completed in 2020, now links communities along the coast that were previously separated by wilderness. Before the parkway and its connector roads were built, residents and tourists in the town of Alma, for example, would have to drive inland to the provincial highway to travel to St. Martins. This disjointed system of roads left communities feeling disconnected from one another, with top-down tourism marketing and development plans over the past few decades compounding this sense of isolation. Those same communities were vying for attention from New Brunswick’s larger urban centres. “Saint John always claimed St. Martins,” explains Fardy, “and Moncton had Fundy National Park.”

The linking of the region’s communities with the opening of the Fundy Trail Parkway has provided the perfect opportunity to bridge differences and build better tourism.

Even as the parkway made travel in the region more seamless, the tourism sector quickly realized it was not quite ready for the increase in visitors the parkway was built to generate. Indeed, the town of Alma, where Fardy lives, was so overcapacity in the summer of 2023 that the municipality issued a boil-water order. This wasn’t because of a water quality issue but because the local reservoir, built to serve a winter population of 280, was so taxed it was pulling up sediment. The municipal government asked businesses to limit their water use and close publicly accessible washrooms.

As well, the shortage of affordable housing across the region affects locals and seasonal tourism workers who need places to stay during the busy summer season. And residents are deeply concerned about littering and the impact of increased use on local trail systems.

Then there are the cruises, which are set up to bring busloads of tourists straight from the pier in Saint John to the wharf in St. Martins and then back again in a few hours. The crowds come, but they don’t generate much revenue for the community. “It’s like, we’ll get you to the St. Martins sea caves and throw some chowder in you,” says Thorne. “The expectation has been that the local community should just step up and deal with it even though they didn’t ask for it.”

“Folks were getting frustrated seeing investment take place in the area and not seeing work progress in ways where we could see the benefit,” says Fardy. “We always had these conversations on the backs of paper napkins. When COVID hit, we suddenly had a bit more time to think through a different approach to community well-being.”

It was a crisp late fall day, the calm before the storm. Fall colours were over, but it would be a month yet before skiers and snowboarders descended on the Poley Mountain ski resort just outside Sussex to enjoy the powder on the 30 trails that snake down the side of the mountain. Tourism operators, local government officials and Rural Upper Bay of Fundy residents took advantage of the between-seasons lull to gather late last November at the resort for the first Fundy Connects Summit. The goal was to consult with communities in a way that had never been done before, to hear both their concerns and their hopes for the future. One of the highlights was Dor Assia, project manager- community economies pilot, at Shorefast, a charity that runs Newfoundland’s famous Fogo Island Inn and administers everything from arts programming to a sustainable fishing operation on the island. Shorefast now guides other communities looking to “unleash the power of place.”

Back in 2020, when Fardy and other community leaders, including Bay of Fundy Adventures owner Mike Carpenter, started hashing out solutions to the region’s tourism challenges, they knew they wanted to include tourism as one part of a more holistic approach to community development. What they didn’t need was another marketing plan. They formed a working group, surveyed the community about tourism and development, and began researching regenerative tourism and how to apply it to the Rural Upper Bay of Fundy.

Working group member Phyllis Sutherland was sceptical at first. A veteran tourism operator who’s owned the Ponderosa Pines Campground at Lower Cape for 60 years, she felt her concerns about tourism in the region had, in the past, fallen on deaf ears. But after just one lunch with Fardy in 2022, she was convinced. “They weren’t concentrating on marketing, but on care for communities,” she explains.

The group presented an initial community-led plan for the Rural Upper Bay of Fundy Tourism Network in 2022, receiving funding and destination development support from the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency and Tourism New Brunswick. It has since added a baseline research and analysis report, including the survey results outlining the communities’ concern for the environment and support for sustainable development — and how disconnected locals previously felt from tourism planning.

Now the work is to turn research into action. On the phone from her home in Alma, Fardy outlines some of the ideas she and other working group members have been discussing with communities along the parkway. With the lines of communication now open between communities, organizations and government, everyone is excited about the potential for creative collaboration and partnerships.

A bank dating back to the 19th century in Riverside-Albert that desperately needs repairs, for example, has the potential to be renovated for a social enterprise and to boost the amount of affordable housing available for locals and seasonal residents flocking to the region for summer work. And Fundy Park closes much of its staff accommodations each year after Labour Day weekend, so why couldn’t the partnership and the park consider hosting an artist retreat there in the off-season, similar to the ones at Fogo Island Inn? The ideas are endless; the enthusiasm is contagious.

Municipalities are working together more closely to build shared infrastructure, like trail systems linking towns. And the partnership with all levels of government opens up opportunities for financial and knowledge-based support for tourism businesses looking to make their operations more environmentally sustainable. “It’s very rare that you get to be involved in a project of this scale,” says Thorne. “It presents that opportunity to be part of something greater than yourself.”

It’s raining again when my family and I get to the sea caves in St. Martins, but no one cares anymore. We’re covered in mud and full of coffee and cookies from the nearby Shipyard Cafe, a cosy little coffee shop on the main level of Bay of Fundy Adventures, which hosts everything from guided tours of the sea caves to multi-day hikes on the arduous Fundy Footpath.

Even in the rain, dozens of people walk the shore. Some peer out at the vast expanse of the bay, trying to

find the horizon hidden under the cloudy haze. Others crouch down to get a closer look at the palm-sized rocks that cover the beach, rubbed smooth from the constant churn of the tide. The caves themselves are a deep sandstone red. Ewan points out how dark it is inside them, before verifying that no ancient monsters lurk within them: “But there’s only rocks inside, right?” he asks.

The Bay’s giant tides have a way of putting in perspective just how big and ancient the world is and how small and ephemeral you are. You go there to connect, to feel a part of something larger than yourself. It’s no coincidence the communities here, inspired by this incredible landscape, want to be part of something larger too.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the November/December 2023 Issue

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Mapping

As Canada's most famous trail celebrates its near completion, Esri Canada president Alex Miller discusses the ambitious trail map that is helping Canadians get outdoors

Travel

An ancient Mi’gmaq migration route that follows the Nepisiguit River’s winding route to the salt waters of Chaleur Bay, the Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail is now one of the world’s best adventure trails

Travel

Inspired by age-old travelways, a new canoe route knits together the Trans Canada Trail