People & Culture

Rivers of resistance: A history of the Métis Nation of Ontario

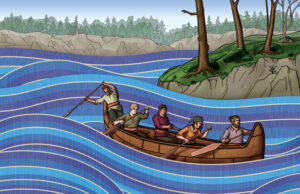

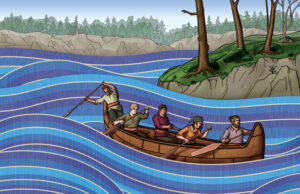

“We were tired of hiding behind trees.” The ebb and flow of Métis history as it has unfolded on Ontario’s shores

- 4405 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

It was a simple yet powerful idea. Plant 100 poppies in 100 cities to mark 100 years since the First World War began.

And retired librarian Teresa Glover started the project in her own yard.

“My feeling was that there was such a huge loss in that war that it must have touched every village and town in Canada,” Glover says. “So maybe we could do something very simple just to show we didn’t forget.”

Glover decided to email majors all over Canada to see if they would be willing to plant 100 poppies. She emailed the mayor of Cobourg, Ont., her hometown, and received a reply the next morning saying he liked the idea.

She wrote to over 100 mayors and received replies from 84 saying they would plant the poppies. Many of them have promised pictures and any articles written about the planting. Glover’s favourite story so far is from Abbotsford, B.C., where a Grade 2 class and veterans from the local legion planted the poppies together.

Glover’s drive has also garnered support outside cities. Horticulture groups have jumped on board, and Glover says a group in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. purchased 300,000 seeds to distribute for free in the area.

Though it’s nearing the end of poppy planting season and she’s currently around 16 cities shy of her goal of 100, Glover says she hasn’t given up. “Spring is the best time, so another couple of weeks will be too late, unless they just plant perennials from the garden centres.”

Why is the poppy a symbol of remembrance?

The poppy was made famous in John McRae’s poem In Flanders Fields. But we don’t wear a poppy on Remembrance Day because of McRae’s poem. It’s another poem written three years after McRae’s which made the poppy the symbol it is today.

The last stanza of Moina Michael’s 1918 poem We Shall Keep The Faith reads:

“And now the Torch and Poppy Red

We wear in honor of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

We’ll teach the lesson that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the July/August 2014 Issue

People & Culture

“We were tired of hiding behind trees.” The ebb and flow of Métis history as it has unfolded on Ontario’s shores

History

Sites across Canada honouring the war

History

Une rétrospective des débuts de l’institution fondée il y a 350 ans, qui revendiquait autrefois une part importante du globe

Science & Tech

The Vice-President of Global Business Environment and head of the Shell Scenarios team discusses the Future Cities project and how Canadian cities can be more sustainable