If there’s one thing that’s true about COVID-19, it’s that the scale of direct transmission is local. Which is to say that to acquire the virus you must come in personal contact with it. The safe zone, we are told, is two metres. If you are more than two metres from the virus, you are almost assured not to get it.

And yet, the scale of the virus, over the short time since it has jumped from animals to humans, is also clearly global. And the pathway for this jump from a scale of less than two metres to the scale of the planet is all about the varied nature of modern human movement. Local, regional, national and international travel has moved the virus at an incredible rate from (presumably) a single location to the entire planet.

Visualizing how this world-changing virus has spread is a job cartographers the world over have taken up since the pandemic began. But unlike many geographically-rooted stories, this one is all but impossible to distill into one map. One simply cannot map the transmission from person to person, the journeys of infected peoples around the world and the relative global incidence all at once. There are maps of all kinds circulating around the Internet, using different scales and different cartographic tools to try and answer the myriad questions we are all asking. But not all maps are created equal, and I am going to spend this, and future posts exploring the good, the bad and the ugly of the seemingly endless COVID-19 maps.

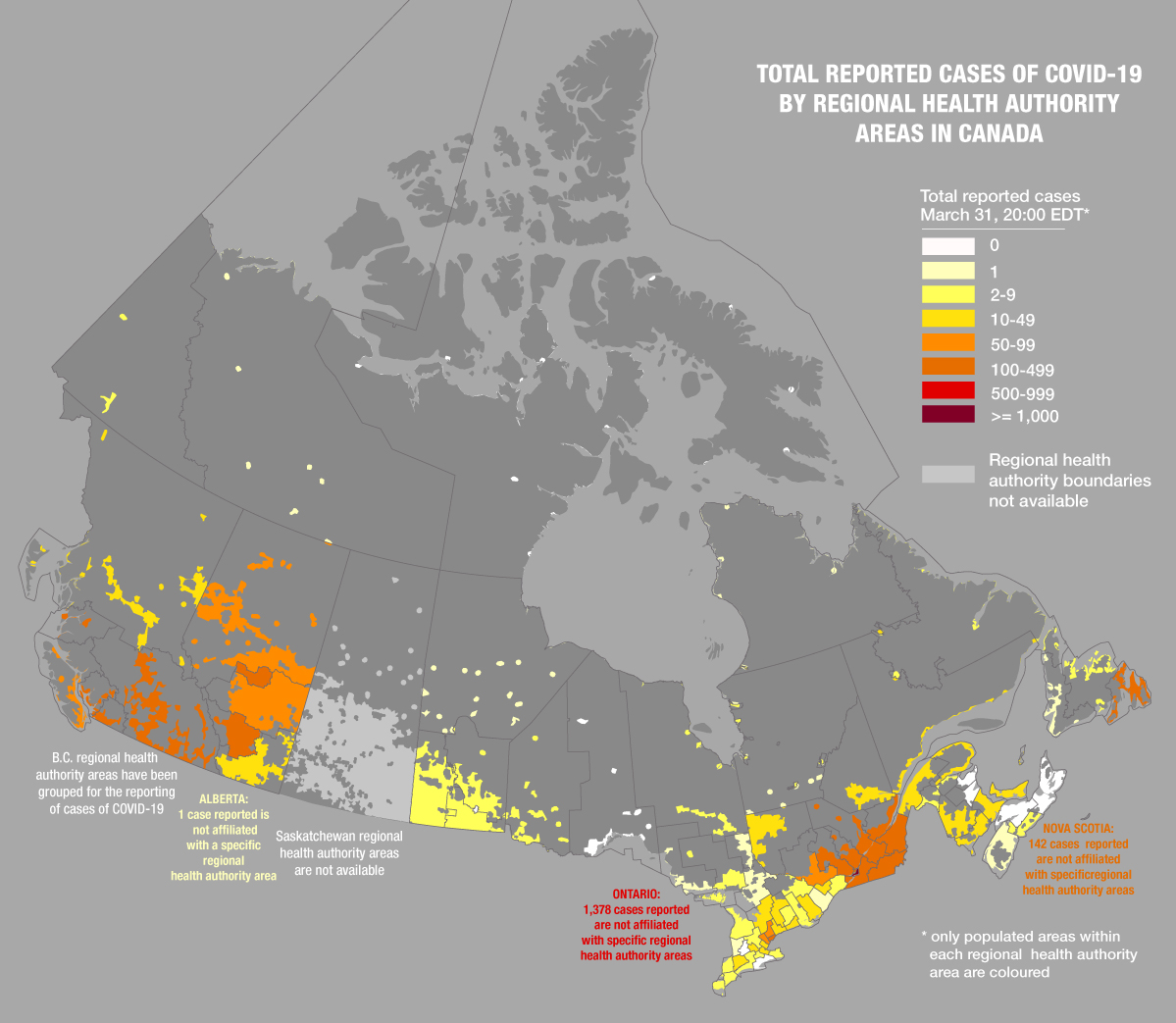

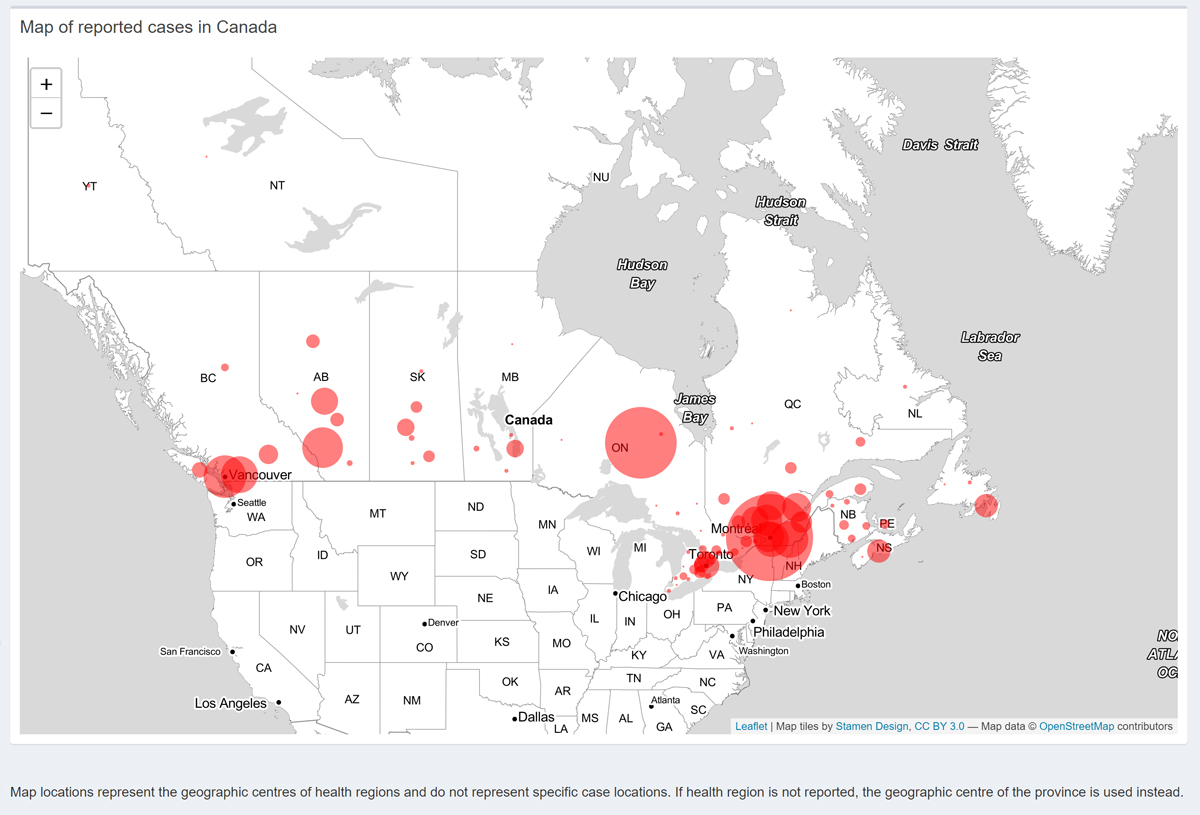

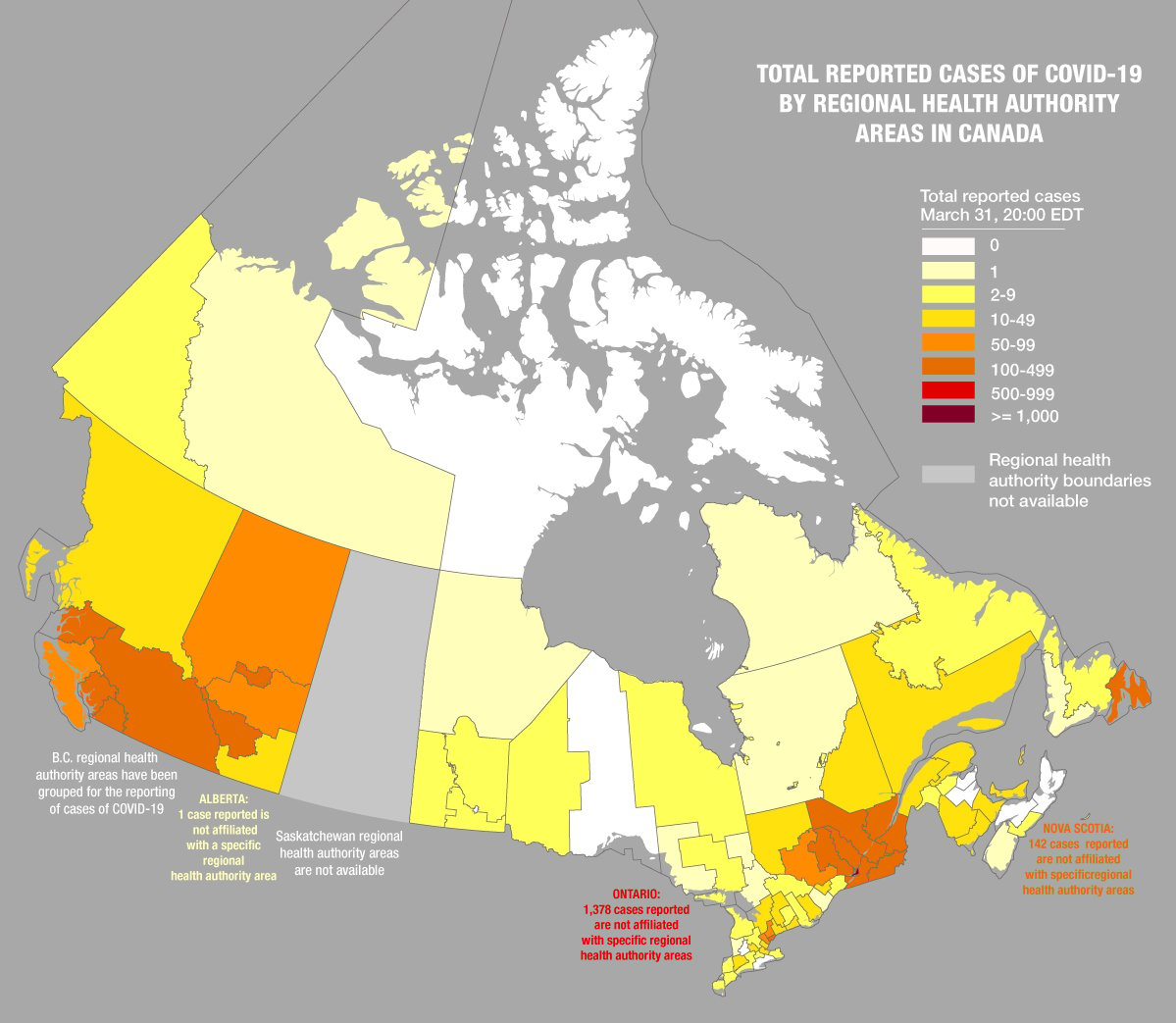

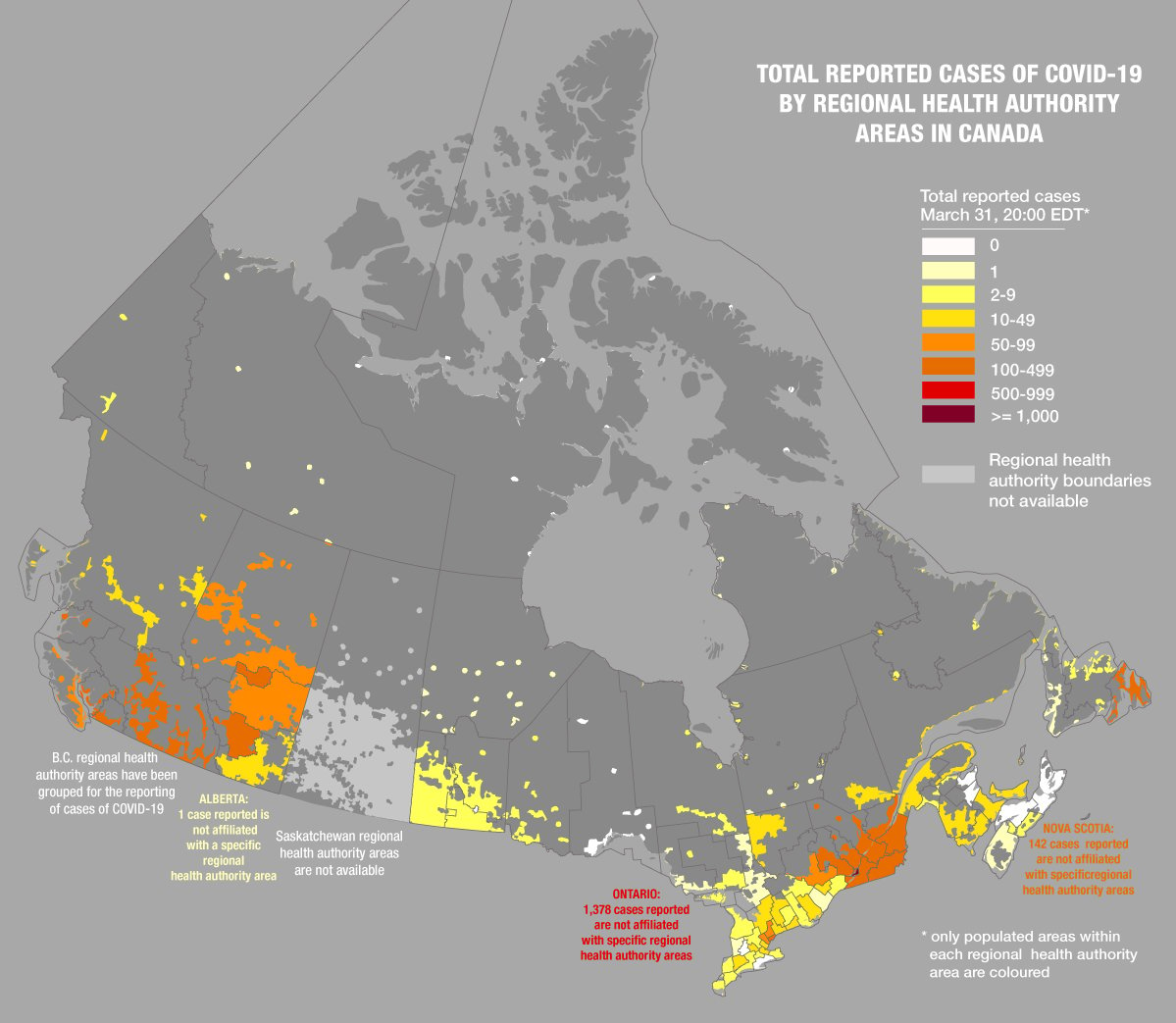

One of the most pressing questions for those of us living in self-isolation is “how likely am I to get COVID-19?” Your own behaviour is, of course, the best defence (wash your hands, don’t touch your face, etc.), but another important consideration is, “does anyone around me have it?” With this question in mind, many of us are turning to online maps, updated daily, to try and make some meaningful assessment of our risk of coming into contact with the virus when we creep out to resupply. The now ubiquitous comparative global maps, showing relative national numbers around the world, are not highly instructive, as Canada is a big place.

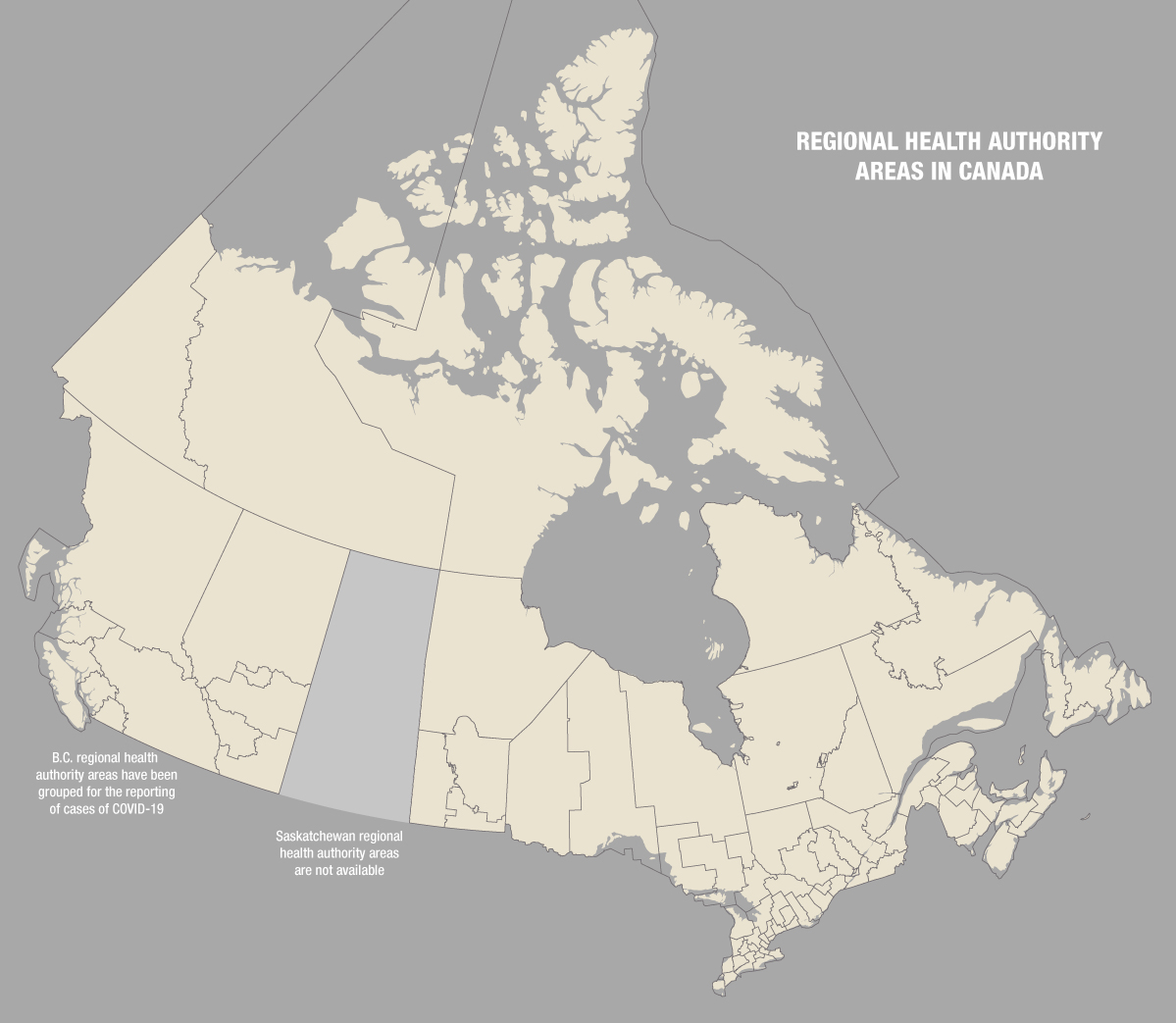

For a nation the size of Canada, breaking down the numbers into more local geographies is necessary. Provincial maps are an improvement, but there is even more granular information available. The numbers of confirmed cases are being collected by provincially managed regional health authorities, and though it would be great to get even more spatially detailed information, it seems that this is the most granular suite of credible data currently available. The regional health authority areas are not well known geographies, so here is what they look like across Canada (note: in B.C. some areas have been merged for reporting purposes during the pandemic, and the Saskatchewan Health Authority has redrawn its boundaries, but are not making the extents publicly available).