Exploration

The pull of Everest

A century after a Canadian was instrumental in charting the world's highest peak, a fellow Canadian reflects on the magnetism of Everest

- 4083 words

- 17 minutes

Travel

Garbage litters the trail of the world’s most popular trek, but measures are being taken to clean up the Khumbu region — one kilogram at a time

It’s pitch black, just after 5 a.m., and my fingers and toes already feel frozen. I am wearing every layer I brought to Nepal, but the early morning Himalayan chill is still seeping through my clothes.

Everything is quiet except for the heavy breathing of trekkers behind me and the ice crunching beneath our boots. A fresh blanket of snow covers the ground, glittering as shards of ice reflect the light of my headlamp, revealing what looks like a starry night sky beneath my feet. My eyes are fixed on the path ahead as I carefully follow in the footsteps of Kami Sherpa, one of our guides. We are ascending Kala Patthar, an 18,519-foot peak in the Everest region.

We’re paying close attention to the steep ground to avoid slipping. It’s mainly rock, ice and snow, all organic materials in their rightful place. But the light of our headlamps also catches the glint of discarded candy bar wrappers and old water bottles — plastic waste where it shouldn’t be.

Mount Everest is the world’s highest dumping ground, and the route to get there is one of the most popular treks in the world. Twice a year, approximately 40,000 trekkers, local guides and Indigenous sherpas will journey to Everest Base Camp, contributing to more than 200 tonnes of waste in the region per year. The annual influx of tourists has also contributed to a building boom as local communities race to accommodate more and more people each year.

When expert leader and Exodus Travels guide Valerie Parkinson began guiding here in 1986, the scene was very different. “When I first started, there was nothing. You couldn’t get anything,” she says. “When I first started trekking, there were no lodges; everything was camping. [Since then], the size of the villages has increased, and building materials now are concrete rather than wood. There is more availability of things like Coca-Cola, Sprite, Mars bars and Snickers.”

Parkinson has spent a significant amount of time trekking in the Himalayan region. In 2008, she became the first British woman to summit Mount Manaslu without the use of supplementary oxygen, and in 2009 she attempted Everest. “When people think of Nepal, they think of Everest,” she says. “And it’s getting busier and busier.”

For most trekkers, the journey to base camp begins in Lukla, a small town in the Khumbu Pasanglhamu rural municipality. It is home to arguably the world’s most dangerous airport, the Tenzing-Hillary Airport. Enclosing the airstrip on one end is a 600-metre drop, at the other end, a solid stone wall. As the gateway to the Everest region, this is also where the majority of supplies are flown in, either by plane or helicopter.

The journey to Everest Base Camp takes approximately eight days, covering more than 60 kilometres. Trekkers will pass through towns such as Lobuje, Gorak Shep and Namche Bazaar, a prosperous Sherpa town, while witnessing some of the world’s most incredible scenery. In Lukla and beyond, mountain peaks surround the trails, providing outstanding views of mountains like Lhotse, Ama Dablam, Makalu and, of course, Everest.

But amid the prayer rocks, rhododendron trees and suspension bridges is a growing sea of rubbish left behind by porters and trekkers — sweet wrappers, instant noodle packets and biscuit wrappers.

Scattered along the Everest Base Camp trail are about 100 garbage bins installed by the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), a non-profit and non-governmental organization established to keep the Khumbu region clean. Situated at natural rest stops, the bins encourage trekkers to separate tin, cans and bottles from garbage (burnable from unburnable trash). Since 1991, the SPCC has been working to strengthen community participation in waste management, create a system for waste separation, and find ways to reduce waste overall. Reuse and recycling is a key tenet of the program. The SPCC believes that “waste is not waste until it’s wasted,” a notion that has been adopted by other organizations in the region.

Just past the airstrip of Syangbouche and before stopping in for a cup of masala tea at the iconic Everest View Hotel, trekkers pass by the newly built Sagarmatha Next Experience Centre, where they can learn and experiment with waste from the Himalaya. Opened in Spring 2022, Sagarmatha Next supports sustainable tourism in the Khumbu region.

“We want to be active here in this region,” says Tommy Gustafsson, co-founder of Sagarmatha Next. “In Kathmandu, it’s very hard to drive a project like this up here. You have to be present in the communities, with the local people, to actually have them commit to it.”

Sagarmatha Next is also home to the Denali Schmidt Art Gallery, where artists are encouraged to focus their creativity around the environment and sustainability, experimenting and pushing the boundaries of art to create visual messages for all of humanity.

Pieces of metal art by Canadian artist Floyd Elzinga line the walls of the gallery. Sponsored by the Denali Foundation, launched in 2015 in memory of Denali Schmidt, who died in an avalanche while climbing K2, Elzinga spent several weeks at Sagarmatha Next as part of an artists residency program. While there, he created 25 individual artworks made from waste left in the Khumbu region.

“I wanted to make things out of trash that people would pay for and pay to remove because that’s the crux of the whole issue,” says Elzinga. “I also wanted to create a landmark icon made out of trash that would draw people in and make them go, ‘What is going on here?’”

Against a backdrop of snow-capped mountains and valleys, one of Elzinga’s most prominent pieces, Hope, stands right outside Sagarmatha Next, inviting visitors to come closer and find out more about the centre. Sunlight shines between gaps in the metal sculpture that was originally a telecommunications rack, forming everchanging shadows around the piece. Leftover scraps from the construction of Sagarmatha Next also form parts of the sculpture. “Some of the pieces didn’t even make it to the waste pit,” says Elzinga. “The centre had a scrap metal yard, and many things were collected on site.”

Elzinga collected other pieces for his work from the 26 waste pits throughout the Khumbu region holding trash from the bins installed by the SPCC.

When we finally reached Everest Base Camp after more than a week of trekking, I felt an overwhelming sense of accomplishment and gratitude — both toward myself and to the landscape around me. I have done a fair amount of travel, but the magic of the Himalaya is unique.

To celebrate our achievement and document our success, my Exodus Travels group of 11 trekkers, Parkinson (our lead guide), and three local guides had our picture taken at the iconic base camp rock. It was a highlight for me, but one dampened by the sight of the trash that had collected beneath this Himalayan landmark.

Trekking with Exodus Travels gave me the reassurance that I was travelling sustainably and responsibly. The company is committed to economic empowerment for local communities and marginalized groups, minimizing the use of single-use plastics and rewilding 100 square metres for every passenger. Our leaders encouraged us to avoid buying plastic water bottles and to instead use SteriPens or other methods of water purification. In addition, we visited local communities and were educated by Parkinson on the culture and practices of the region. But although our group did our best to minimize our impact on the environment, we wanted to do more.

The first initiative of Sagarmatha Next, Carry Me Back is a project that was started to address the waste management challenges in Sagarmatha National Park and the Khumbu region. A crowdsourced waste removal system, Carry Me Back is designed to send waste to its rightful place, where it can be recycled appropriately. Sagarmatha Next and the SPCC work together to segregate waste and pack garbage into one-kilogram bags that can then be “carried back” by trekkers and locals. Participants pick up the bags and carry them back on their return from base camp just outside of Namche Bazaar. They drop them off in dedicated bins in Lukla, where a local private airline transfers the waste back to Kathmandu to be properly recycled.

Each member of our group carried one bag back — adding one kilogram of weight to our already heavy daypacks did not make much difference. The Carry Me Back initiative was a great way to end the trip, knowing that in our small way, we each contributed to making a difference.

After just over two hours of climbing in the shadow of the mountains, we finally made it to the summit of Kala Patthar. My head was pounding from the increased pressure at high altitude, and I could barely manage to take out my camera to capture the view as my fingers had gone numb. It was cold and we were tired, but I was happy. Surrounded by colourful prayer flags, we stopped to reflect on our accomplishment just as the sun began to peek out from behind the top of Mount Everest. It was a moment I never thought I would experience, but I am grateful to have witnessed the beauty of the Himalaya firsthand.

Everyone knows the name of the tallest mountain on Earth, but the biggest story is bigger than Everest. Trekking significantly impacts the environment, but there are things travellers can do to reduce their impact on the Khumbu region. “If everyone takes one kilogram, it can make a huge impact,” says Gustafsson. “And if we start now, more will follow.”

Travel with us

Annapurna Sanctuary Photography Trek

This classic trek in the Annapurna is one of the best in Nepal. Join the adventure with the Royal Canadian Geographical Society accompanied by renowned photographer and Canadian Geographic Creative Director Javier Frutos.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

A century after a Canadian was instrumental in charting the world's highest peak, a fellow Canadian reflects on the magnetism of Everest

Exploration

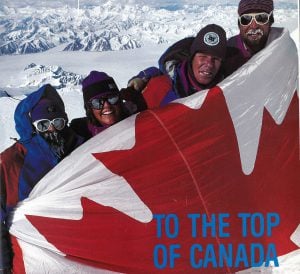

In 1992, a team backed by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society became the first to accurately measure the height of Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak

Environment

They sustain us, enrich our lives and inspire us

Environment

Doing your part as an eco-conscious consumer doesn’t end once you buy a bioplastic product