Environment

Climate change is affecting vegetation in Yukon. What should we do about it?

Yukon-based ecologists uncover four main patterns influencing changes in Yukon and address how outcomes can be improved

- 1621 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Making a great map, as any cartographer knows, requires careful thought. Making a great map of one of the human body’s most important organs is, well, a far more cerebral affair. Just ask Alan Evans. The professor from Montreal’s McGill University is a lead researcher with the BigBrain project, the world’s first 3D high-resolution map of the brain, which was unveiled in June.

BigBrain shows the organ at a resolution of 20 microns (there are 1,000 microns in a millimetre), making it 50 times more detailed than an MRI image. In cartography terms, that’s akin to switching from a two-dimensional paper map of the world to Google Earth. Exploring the geography of our grey matter with that level of precision gives scientists a revolutionary spatial understanding of how different parts of the brain relate to one another, and could help with everything from guiding the placement of electrodes for Parkinson’s disease treatments to gaining insight into aging and neurodegenerative disorders.

To create the reference brain, researchers in Germany took the brain of a 65-year-old woman and sliced it into 7,404 slivers. Evans’ team at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital at McGill University then spent the next four years fixing the digitized images’ “wrinkles, rips and tears” and piecing the images back together.

Over the next two years, the team aims to gather data that will allow researchers to zoom in even closer — to a resolution of just two microns. But with a terabyte of data already collected, the question is whether they’ll be able to store a dataset 1,000 times larger than the current BigBrain. “We are racing with the technological evolution of computer hardware,” Evans says. “We’ll be ready for it.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

Yukon-based ecologists uncover four main patterns influencing changes in Yukon and address how outcomes can be improved

People & Culture

The history behind the Dundas name change and how Canadians are reckoning with place name changes across the country — from streets to provinces

Environment

The uncertainty and change that's currently disrupting the region dominated the annual meeting's agenda

Science & Tech

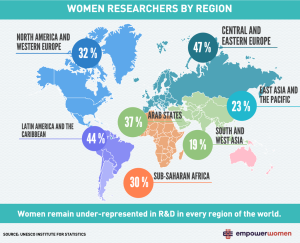

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields