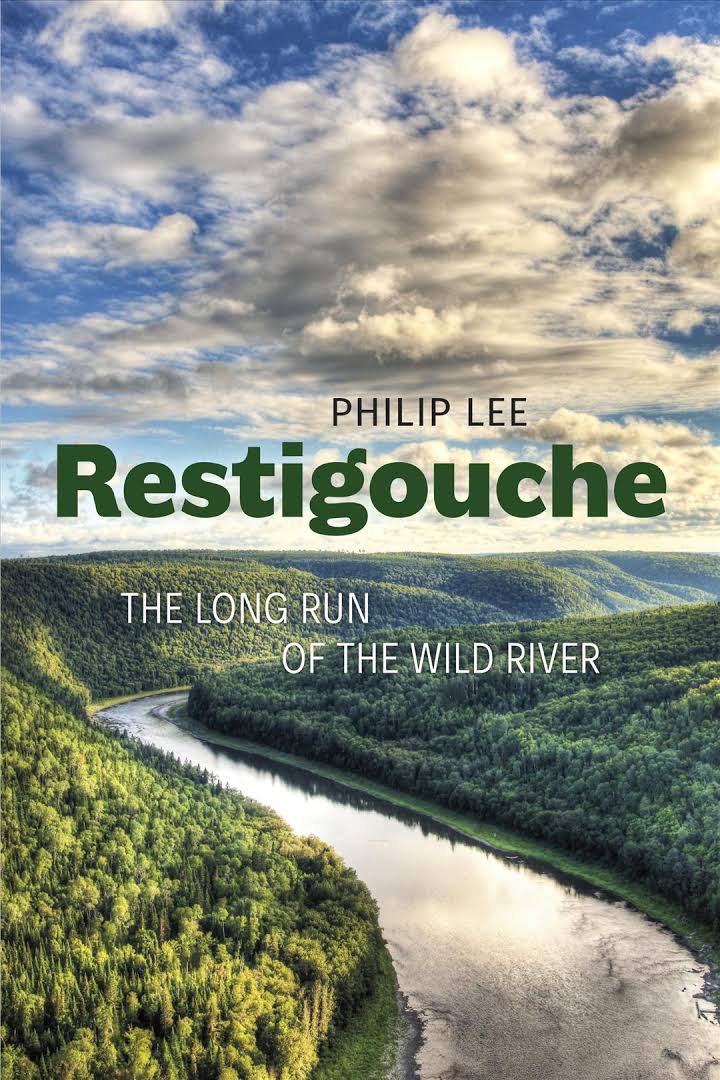

The Restigouche River flows through the remote border region between the provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick. Its magically transparent waters, soaring forest hillsides, and population of wild Atlantic salmon create one of the most storied wild spaces on the continent.

In this book, author Philip Lee follows ancient portage routes into the headwaters of the river, travelling by canoe to explore the extraordinary history of the river and the people of the valley.

Below is excerpted from Chapter 13 of Restigouche: The Long Run of the Wild River.

On the morning of the last day of my season on the river, I had arranged to meet Alan Madden, the former Restigouche biologist who, early in the spring, had directed me to the old portage route at Waagansis Brook. Weeks ago, I had called and asked him to reserve a day so we could run the lower section of the river together to the head of tide. He said he would wait for me at the mouth of the Matapédia on the beach down the hill from the Restigouche Salmon Club headquarters. I pulled anchor and poled down the side channel to the main river, across the tail of the island and the outflow of the Matapédia to the beach where Alan was waiting with a small cooler that served as both lunch pail and gear box. He had with him his fishing rod and a wooden paddle. He was wearing faded jeans and a dark purple long-sleeved shirt, rubber boots and a floppy green hat. He stepped into the front of the canoe and we pushed off into the current. He stood in the front leaning on his paddle watching for rocks, from time to time turning all the way around so we could have a proper conversation. I stood in the back with the pole, keeping the nose of the canoe pointed downstream.

There was still heavy mist down in the valley as we floated through the big pool below the mouth of the river, passing the giant bridge piers that Sandford Fleming had designed for the Intercolonial Railway almost a century and a half ago. We were twenty-five kilometres west of Chaleur Bay where the river splinters into a maze of cross and side channels that flow around more than two dozen uninhabited islands, creating wild spaces for nesting ducks and bald eagles; a myriad of fish species; beavers, mink and otters; marsh grasses and fiddlehead ferns; tangles of wild grape and alders; and stands of towering maples, poplars and spruce. All this rich landscape stretched out before us, and Alan had many things to show me. As the heat of the sun burned away the mists, Alan began a lecture in river history and science that continued throughout our September morning canoe run. A train rumbled past us along the Quebec shore as we followed the channel down past the highest island in the archipelago, called Bell’s. It is long and substantial with a stand of mature hardwoods and spruce in the centre. “That island has wild grape on it, just like the islands on the Saint John River down below Fredericton,” Alan said.

When the current pulled us closer to the Quebec shoreline, Alan pointed and said, “There’s milkweed right there,” and asked me to land the canoe so we could have a closer look. Above the stand of milkweed, a cluster of staghorn sumac trees was growing, their leaves just beginning to turn, always among the first to mark the changing season.

We eased the canoe back into the flow along the north side of Long Island where we floated across a stretch of shallow water and steady current above a wide expanse of fine gravel. This bed of gravel is the most important spawning area in the lower river because here the water flows at the precise speed that allows female salmon to dig their nests and deposit their eggs among the tiny stones. We floated past a grassy island and he showed me where a colony of bank swallows, a species of tiny birds with brown heads and white chests that live in holes they dig deep into the soft shoreline, nests on the muddy bank of the meander. “That colony has been here since I’ve been here,” Alan said. Some things haven’t changed in his lifetime on the river, but others have. “It’s all relative really,” Alan said. “We can’t even comprehend how many fish there were in the nineteen-thirties, and people in the nineteen-thirties couldn’t even comprehend how many fish there were in the seventeen-thirties.”

At midday we stopped for lunch on a narrow sandspit on the tail of an island above Morrisey Rock, a high cliff through which the Intercolonial Railway engineers had cut a tunnel in the 1870s. I anchored the canoe off the point, and we set up chairs and watched the currents swirl where the two channels met below us to form one.

Early in the afternoon, as we approached the Tide Head beach, we saw remnants of the log drives, old hand-sawn timbers half buried in the river bottom and the remains of the square-box boom structures, worn and battered but still holding in the current. In the decades since the log drives stopped scouring the river bottom and the Restigouche works to heal itself from the wounds of the logging industry’s first incursions into the valley, Alan Madden has watched the river marshes gradually reform. There is more healing to be done here and all along the shore of Chaleur Bay, where bones of the industrial dream in these ancient Appalachian hills are now scattered far and wide. Some we can see, but most are hidden and unaccounted for beneath the breakers along the coastline, in the soil, in the sediments of lakes and streams and in the atmosphere far above us, the legacy of a time when we imagined ourselves to be the measure of all things. So much has come and gone in this measure that is but a heartbeat in the life of the wild river.

I poled the canoe into the shallows near the public docks down below the Tide Head beach where Alan had parked his car. In the months that followed that day on the river, I have reflected on the many things I learned from this generous man, the most important being how to keep my eyes fixed upon the miracles of creation. A day on the river with Alan Madden is a reminder that every form of life in every realm of nature reveals something beautiful and marvellous in each moment of its passing.

On the drive home I began the long process of unravelling all I had seen and all I had learned. The one thing I knew for certain then was that I had spent a season following the flow of a great river and I would try to find the right words to say what that means

Adapted from Restigouche: The Long Run of the Wild River copyright ©2020 by Philip Lee. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions.