People & Culture

On thin ice: Who “owns” the Arctic?

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

- 4353 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Exploration

The wreckage of a Scottish whaling ship has been discovered in the Canadian High Arctic by researchers from the University of Calgary’s Arctic Institute of North America. The Nova Zembla, which hit a reef and went down near Buchan Gulf off the east coast of Baffin Island in 1902, stands to offer significant historical insight into life in an industry that dominated Canadian waters for centuries.

Michael Moloney and Matthew Ayre, post-doctoral fellows who received support for the expedition from The Royal Canadian Geographical Society, made the discovery on August 31 in just eight hours using drone footage and SONAR imaging deployed on a remote-operated underwater vehicle in a targeted five-square-kilometre search area identified through months of historical research.

“We’re thrilled about this discovery,” says Moloney. “It was the culmination of months of research and preparation, and we can’t wait to continue working with the RCGS to further explore this site.”

“This is a previously unknown archaeological site, and the first High Arctic whaling ship ever discovered,” says John Geiger, Chief Executive Officer of the RCGS. “It is a remarkable story of historical sleuthing supported by fieldwork and adds considerably to the historical record by shedding new light on that treacherous, once great industry.”

Ayre came across details of the Nova Zembla wreck in March of this year while poring over historical documents for his climatological research as part of the Northern Seas project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council where he is compiling baseline information on sea ice and wind conditions in the Arctic. One of the documents was the logbook of the Diana, one of two whaling vessels that rescued the crew of the Nova Zembla, and it contained clues to the whereabouts of the wreck site in the fiord. Shortly after, Ayre then found a type-written version of a diary from a sailor aboard the Diana in 1903, the year after the wreck, which explained how they returned to the wreck site to salvage some equipment, including the rudder.

“I thought, ‘Oh, the wreck is accessible,’” says Ayre. “They’ve gone back to it. They can actually see it, and they’ve taken something from it. That’s when I got interested and told Mike.”

From there, the duo began to compile newspaper records on the wreck, a first-hand account from a diary of a Nova Zembla crewmember, and other documents, cobbling together bits of information to create an extremely targeted search area for an expedition.

In August, the pair, outfitted by MEC, embarked on their voyage through the Northwest Passage and Greenland aboard the research vessel Akademik Sergey Vavilov. The ship departed Pond Inlet, Nunavut on August 30; the next morning at 6 a.m., Moloney, Ayre and crewmembers Ted Irniq and Kelson Rounds-McPherson set out in a Zodiac, battling one-and-a-half-metre swells as they made their way toward the search area, a windblown stretch of beach near Buchan Gulf. They had only a short window of time to find evidence of the Nova Zembla.

“We knew that the beachfront was what we were targeting. That was what we had triangulated from those historical documents. Then it became your traditional sit and wait and stare at a SONAR screen for hours,” says Moloney.

Armed with satellite imagery of what appeared to be the hull of a ship near the wreck site, Ayre and Moloney first set out to discover the nature of the intriguing shape below the water. Unfortunately, that lead turned cold. “It was a collection of rocks,” Ayre says.

However, using an ROV supplied by DeepTrekker, the team was able to obtain SONAR imagery that revealed some promising shapes, including what appears to be one of the anchors of the ship — straight lines and right angles are indicative of man-made materials, says Moloney. But it was on the nearby beach that they discovered the most promising evidence of the wreck. Through binoculars aimed at the shore, Ayre spotted what looked like pieces of wood on the sand, so he deployed a drone and was amazed at what he saw on the monitor. Pieces of spars and large timbers with metal rivets were scattered across the beach. Unfortunately, their drone battery drained in just a few minutes from the cold, so Ayre could only search for a few minutes before he flew it back to the Zodiac with just seconds to spare.

“I reckon this is the cheapest and fastest shipwreck discovery in history,” says Ayre with a laugh.

The discovery of the Nova Zembla offers insight into the little-known social history of the whaling industry. There are very limited accounts of the daily lives of whalers, and particularly the sailors that plied the treacherous waters of the Arctic and contributed to the geographic understanding of the region. For centuries, whaling was an integral part of life in the Arctic and whalers interacted with and, in some cases, integrated into Inuit communities. While the relationship was not always a peaceful one, many whaling companies incorporated Inuit knowledge into their own practices, and later passed that information on to the Royal Navy during their explorations of the Arctic.

“It’s a largely untold part of the story, and with there being so much attention on wrecks like Erebus and Terror, Parks Canada has been largely focused on naval exploration. There’s really no book on whaling activity in the Canadian Arctic written from a social perspective,” says Moloney.

Back home in Calgary, Moloney and Ayre will continue to process their SONAR and drone imagery to pinpoint more evidence of the Nova Zembla. They plan to revisit the wreck site in 2019, and hope to partner with local Inuit to conduct further research on the wreck.

“The whole goal of the expedition was to discover if there’s something there or not,” says Moloney, “and now we’re certain there is.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

People & Culture

In this essay, noted geologist and geophysicist Fred Roots explores the significance of the symbolic point at the top of the world. He submitted it to Canadian Geographic just before his death in October 2016 at age 93.

Exploration

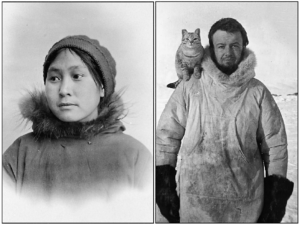

A century after the start of the thrilling expedition that strengthened claims to Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, the first Canadian Arctic Expedition remains a largely unknown part of the country’s history

History

A century ago, a strange drama played out on Wrangel Island in the Russian Arctic. The hero of this tale? A 23-year-old Inuit woman named Ada Blackjack