Environment

Ocean Bridge Diaries: Hannah Kosick

Before joining Ocean Bridge, I was completely unaware of the extent of the problem of single-use plastic consumerism

- 1042 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Environment

“Water bottle! Plastic bag! Bottle cap! Fishing net! Shotgun shell! Rubber tire!”

We walk across the sandy beach, eyes down, sweat beading, shouting out each piece of trash we find.

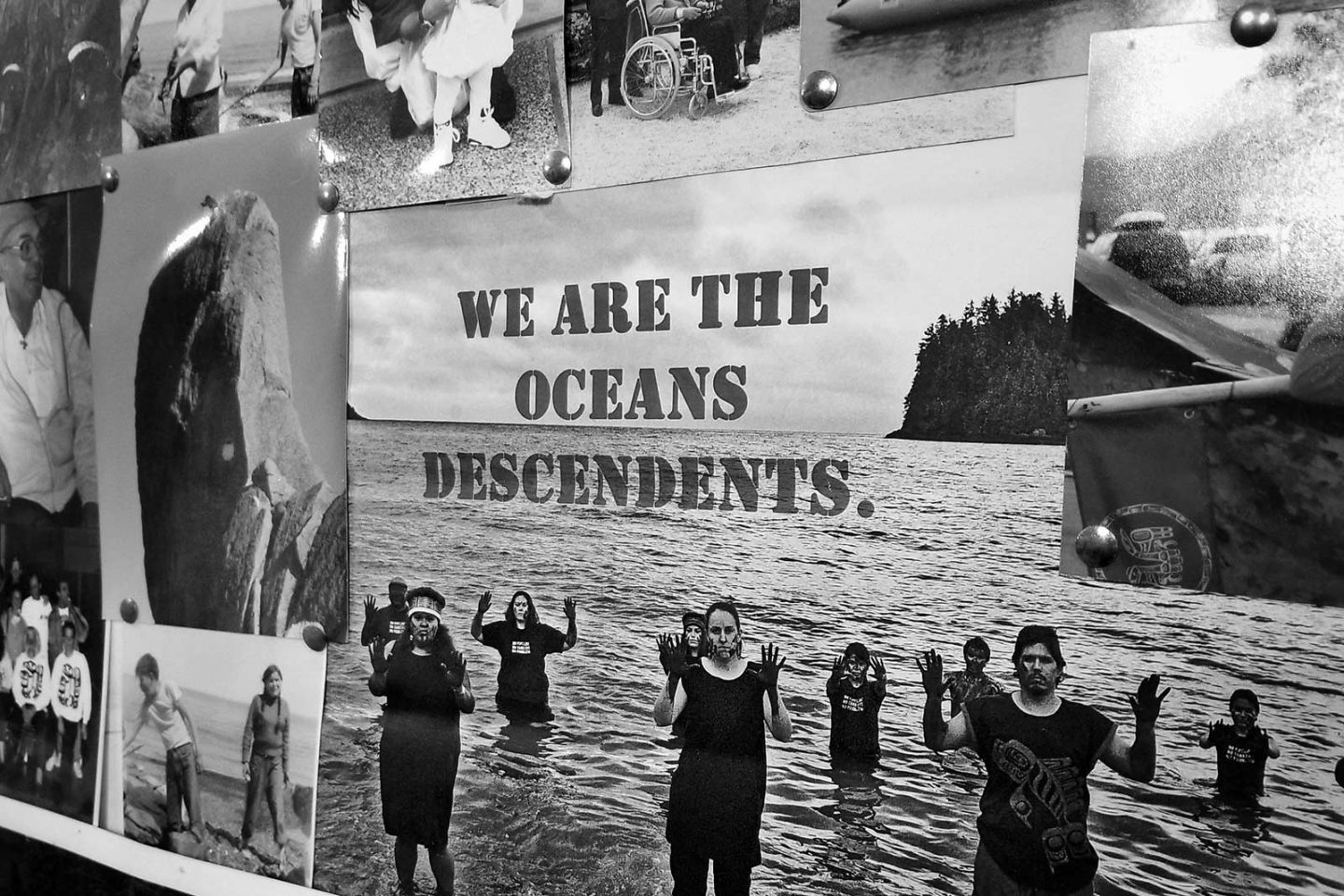

I’m in Haida Gwaii, B.C. with 40 youth aged 18 to 30. They’ve come from all across Canada for a 10-day expedition, part of the year-long Ocean Bridge program, which aims to equip young people with the knowledge and confidence to become advocates for ocean health in their communities. I’m here to photo-document the experience for Canadian Geographic. The next 10 days turn out to be a hands-on, eyes-wide awakening to the problem of plastic debris in the ocean, not just for the youth, but for me. This is the story of why Haida Gwaii has been etched into me forever.

Every one of your senses is heightened as you trek through the islands. Everything has a story. You’ll find hidden passages and ancient Haida totem poles and beached shipwrecks.

To explore this place is to discover an indescribable mythical ambience. It comes from the land, the people, their collective pride in their history. It’s beautiful. People have tears in their eyes when they speak of this place. Everything has meaning. Everyone waves at each other 100 per cent of the time. No words are said without intention. Haida Gwaii has the most love in the world and it’s contagious.

Ocean Bridge is about something that impacts each and every one of us: the health of our oceans. When Canadian Geographic told me I was to plant myself on this archipelago and photograph an ocean youth initiative, I had no idea what to expect. I was amazed to meet 40 driven leaders looking to make a positive difference. These young people are determined. I saw fire in their eyes. The second I spoke to any of them, they immediately lit up and began talking about what they were working on and why. Observing their team dynamic, I couldn’t help but feel proud and inspired.

For me, the most memorable day of the expedition was the day of the shoreline cleanup on North Beach, behind Hiellen Longhouse Village, our basecamp for the expedition. I arrived on the shore that day to find the youth spread out down the beach as far as the eye could see. I joined them in picking up trash, and took photos of them lugging tires, fishing nets and garbage bags filled with bottles and other debris. By the time we reached our garbage drop zone my own backpacks were full of plastic containers bearing labels from around the world. Everyone carried as much as they possibly could without complaint. It was inspiring to see such action.

Once we weighed the full load of trash we learned we had removed more than 1,000 kilograms of ocean debris from the shore in one day! The BC Parks rangers said they had never seen the beach that clean, and local residents were amazed and concerned to see how much waste had accumulated on the shore — most of it from places far away from Haida Gwaii. We made an impact.

Haida means “people.” The Haida have inhabited this region for 13,000 years and these islands have always been the heart of their nation. The ocean is in their DNA and they have navigated the waters and lived off the sea’s bounty since the beginning. It didn’t take long for me to realize that this is a very close community and your intentions must be positive if you are to communicate with and relate to the Haida people. Meaningful conversations and dialogue lead to deeper relations.

As I waited to board my flight from Vancouver to Sandspit, I posted a short Instagram Story of an impressive display of Haida totem poles and boxes in the Vancouver Airport. By an amazing coincidence, at five the next morning I found myself having coffee with the carver himself, Reg Davidson, pictured above in his workshop. Reg is an internationally acclaimed Haida artist and Elder who had a great impact on me during our conversations.

Reg wakes up at 3 a.m. and you can usually find him in the wee morning hours working on a mask or smoking salmon in his smokehouse. I sat across from Reg, surrounded by carvings and artifacts, as he told me about how traditions are weaved into the Haida culture. Sacred learnings are passed down through the generations by the Elders. The Haida history, language, dance, art, and how to fish are all elements of the culture. Developing a symbiotic relationship with the ocean means life for the Haida people. Forming this sacred relationship and relying on the ocean requires you to respect the ocean. Hearing this, I awakened to the fact that we all rely on the ocean.

Oliver Bell was the first person I met from the Haida Nation. He was our link to the local community. Oliver is an artist, carver, family man and fisherman. He learned how to fish when he was only four years old and trained on his uncle’s boat until he turned 18 and became a deckhand. It wasn’t long before Oliver acquired his own fishing licences and vessel, and took to the waters as a commercial fisherman. These days, he takes visitors on chartered fishing tours. Oliver told me the secret to how he attracts the fish he provides to his family and community. It is believed in Haida culture that certain fish can be lured to the boat using specific language and vocal calls, passed down by Haida Elders.

I asked Oliver what the ocean means to him. “200 years ago these beaches were covered in canoes and kayaks,” he said. “The Haida are an ocean people. Our ancestors used to read the clouds — the greys and blacks, the puffiness of the clouds, would all be signals to read the sea. The water is everything to us.”

I’ve been impressed beyond belief by the 40 young leaders from across our country and the team at Ocean Wise. Apart from the physical impact of removing marine debris from North Beach, this program will continue to have reverberations throughout Canada. This expedition was ultimately about 40 people building an everlasting relationship with the environment and each other. I have no doubt that these young leaders will go back to their hometowns to foster new connections and big ideas based on what we’ve all learned.

I asked one of the participants, Danika Lalonde, what she planned to do next. As a student in the Health Sciences Program at the University of Ottawa, Lalonde is interested in understanding and highlighting the impacts of marine pollution on human health. She’s already created an Instagram account dedicated to sharing tips for reducing plastic waste.

“I want to share my story with people younger than I am,” she said. “I believe that if we impact the young, they’ll go on to inspire the next generation.”

My heart beams for the Haida people. Being able to document the Ocean Bridge expedition and spend time in this remote sanctuary has forever impacted my view of ocean life. This will shape my own work moving forward towards environmental awareness and conservation. Haw’aa!

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

Before joining Ocean Bridge, I was completely unaware of the extent of the problem of single-use plastic consumerism

Wildlife

As the sea otter begins its long-overdue return to Haida Gwaii, careful plans are being laid to welcome them — and to preserve a prosperous shellfish harvest

Environment

Bridging the gap between conservation and culture

Environment

We are the ocean, yet we know not who we are, so we went to people who did