Wildlife

Should we kill one bird to save another?

On New Brunswick’s Machias Seal Island, predatory gulls are pushing endangered Arctic tern colonies to the brink, creating a dilemma for wildlife managers

- 2151 words

- 9 minutes

Wildlife

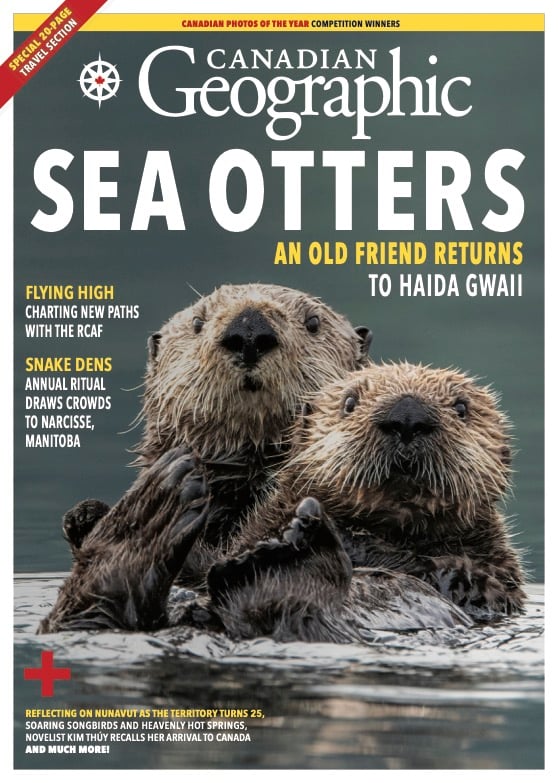

As the sea otter begins its long-overdue return to Haida Gwaii, careful plans are being laid to welcome them — and to preserve a prosperous shellfish harvest

In a strange twist of fate, it was nuclear testing in Alaska that brought back the insatiable, beautiful, long-missed, never forgotten sea otter to the waters of British Columbia. In the mid 1960s, at the peak of Cold War tensions, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission was conducting nuclear trials in the Aleutian Islands, off the western tip of Alaska. Public concern over the testing was rising, and a rag-tag group of 12 activists set sail from Vancouver in an old fishing boat. On the journey over, the group settled on a name: Greenpeace.

When Atomic Energy Commission staff discovered a population of cuddly sea otters at their next test site, they feared a public-relations disaster. To avoid an outcry, they captured and relocated hundreds of otters — airlifting them in aquarium-like tanks to sites in southeast Alaska, Oregon, Washington and the west coast of Vancouver Island. The 89 sea otters relocated to Vancouver Island were the first British Columbia had seen in 40 years.

With the thickest pelts of any mammal, sea otters were highly coveted by fur traders. Russian ships, followed by Europeans, arrived on the west coast of Canada in the 18th century and began selling furs to overseas markets for high fashion, with China being the most popular destination. At the peak of the fur trade in the 1800s, four luxurious, silver-tipped sea otter pelts could fetch enough money to buy a house in Victoria. But as quickly as the market boomed, it went kaput. The global population of sea otters crashed from upwards of 300,000 to just 2,000 by the early 20th century. Along B.C.’s coast, they were wiped out entirely, the last one shot in 1929.

As explosive as their demise was, so too was their reappearance. The sea otters transplanted to Vancouver Island quickly re-established themselves, growing in number and spreading around the island and across to B.C.’s mainland. To the north, however, the similarly affected archipelago of Haida Gwaii — once home to a thriving sea otter population, estimated between 5,000 and 10,000 — was left waiting.

Made up of some 150 islands off the coast of northern B.C., Haida Gwaii is the ancestral territory of the Haida people (roughly half of the islands’ population today is Indigenous). Sea otters — known as Ku or Kuu in the Haida language, depending on the clan — are an iconic creature for the Haida, appearing in dozens of oral histories and depicted on countless totem poles. In one Haida history, a hunter kills a sea otter without giving thanks for its life. When he gifts the pelt to his wife, the sea otter springs back to life and swims away. His wife gives chase but is captured by a pod of SGaan, or killer whales, leading to an adventurous rescue.

For nearly a century and a half, the archipelago remained otter-free. But in the last decade or so, rumours began swirling that the charismatic creature had returned. Like reports of Bigfoot, there were intermittent sightings: usually of lone male sea otters, floating on their backs and munching on spiny urchins. The nearest population to Haida Gwaii was some 130 kilometres east, across KandaliiGwii (Hecate Strait) — a gruelling swim, even for a hungry otter. But in 2019, news broke that staff with the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area and Haida Heritage Site, in southern Haida Gwaii, had spotted a female with pups: proof that sea otters had finally come home.

The sea otters’ return is often seen as a heartwarming conservation story, but it also brings its challenges. Sea otters are voracious shellfish eaters.

Diving to depths of up to 100 metres, they can gobble a quarter of their body weight daily in urchins, crab and abalone — a much-prized seafood for coastal First Nations. On Vancouver Island, sea otters have been a point of tension among Indigenous groups and shellfish harvesters ever since they were airlifted in. In southern Alaska, there have been calls for sea otter culls (a limited Indigenous hunt is currently permitted). On Haida Gwaii, too, now-abundant shellfish have become an important resource, and there are similar concerns. What if sea otters change the coastline in ways that affect livelihoods and limit shellfish foraging?

“We knew the otters were coming; it was just a matter of time,” says Cindy Boyko, co-chair of the Archipelago Management Board, a partnership between the Council of the Haida Nation and Parks Canada that oversees Gwaii Haanas (“Islands of Beauty” in Haida). Boyko was born and raised on Haida Gwaii. She describes spending her childhood summers gathering shellfish and seabird eggs and joining her family on fishing trips. For the past two decades, she’s been a driving force behind local marine conservation efforts. Still, when she first heard news that a breeding female sea otter had been spotted, she admits her response was decidedly mixed. “I thought ‘oh no!’” Boyko says. “But then, I knew we had to do something.”

The shellfish harvesting industry today employs hundreds of people in B.C., many in small, remote communities like those on Haida Gwaii. Demand comes from a global market, says Geoff Krause, a marine biologist with the Pacific Urchin Harvesters Association. Urchins — spiny, softball-sized creatures that live on the ocean floor and devour kelp — are considered a delicacy around the world, often served in fine seafood restaurants (their flesh is like salty pudding). Abalone — a marine snail with a hard, opalescent shell often used in Haida jewelry, and another sea otter favourite — is even more coveted.

— Guujaaw, artist and a hereditary leader of Haida Gwaii (from the poem “The Innocent”)This is the one

who would eat all day

yet never get fat

whose beauty would be its own undoing

Krause says areas where sea otters have been reintroduced have seen a dramatic decline in shellfish. “Back in the 1980s, about 25 to 30 per cent of the harvest for red sea urchins in B.C. came from the west coast of Vancouver Island,” he says. “Now it’s basically zero.” He fears the same thing could happen if sea otters repopulate Haida Gwaii, jeopardizing jobs. “When the otters show up, usually within a couple of years there’s no commercial quantities of urchins around anymore,” says Krause.

While a thriving shellfish population might be good for business, it also indicates an environment deeply out of whack. Because, though Ku/Kuu consume greedily, they repay with equal generosity. When an area of the ocean is devoid of sea otters, urchins can run amok. Where there should be waving fields of kelp, instead the ocean is nearly empty of greenery.

Perched on the side of an eight-metre inflatable Zodiac boat, clad in a wetsuit, mask, snorkel and fins, is Lynn Lee, a senior marine ecologist with Parks Canada. The boat is anchored a stone’s throw from Murchison Island, an uninhabited rocky outcrop on the eastern side of Gwaii Haanas covered with towering western hemlock and Sitka spruce.

Here, the results of a kelp restoration project provide a glimpse at what this rugged coastline might look like when sea otters repopulate it. The project was launched in 2017 through a partnership between the Council of the Haida Nation, Parks Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Sea otters are considered a keystone species, Lee explains. Like wolves in Yellowstone National Park, they play an outsized role in shaping their ecosystem. The main way they do this is by eating urchins, which, in turn, allows kelp to thrive. When Haida Gwaii’s sea otter population collapsed, so did many of its kelp forests. Those kelp forests provide refuge for a variety of other marine life, particularly juvenile fish. It’s an example of what ecologists refer to as a “trophic cascade.”

For the kelp restoration project, a team of commercial shellfish harvesters were brought in to remove most of the urchins from a three-kilometre stretch of coastline — essentially mimicking what would happen if sea otters lived here. Over a week, divers hauled out — or simply smashed with pickaxes — a whopping half-million urchins. Five years later, Lee says the difference is striking.

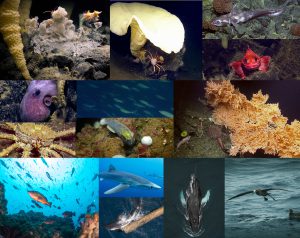

Lee looks down at the choppy water below, pulls down her diving mask and plunges into the long, tangled mats of kelp as thick as garden hoses. Below the surface, a whole different world opens up: golden-green kelp fronds wave in the currents, perch and sunfish dart among the leaves, and further down — barely lit by shafts of sunlight — is an understorey of more delicate plant life. Closer to the shore, a giant purple sea star and then a lion’s mane jellyfish, its fringe of orange tentacles floating beneath it. It’s an otter’s-eye view of a rich, diverse underwater forest.

After the urchins were removed, Lee says the recovery of kelp and other sea life was almost immediate. Bull kelp, an annual species that can grow up to 25 centimetres a day, took hold first, followed by other aquatic plants and marine life. The results fluctuated from year to year (the extreme heat wave in 2021 led to a die-off of kelp and feeder fish), but overall aquatic health has improved measurably. “It has started to evolve into an old-growth forest situation, where you have different species coming in and more diversity and different kinds of kelps,” says Lee.

When the project began, there was virtually no kelp or any other marine life, aside from the urchins carpeting the seabed in what’s known as an “urchin barren.” Without sea otters, this is what much of the coastline of Haida Gwaii looks like today. It’s no wonder, then, that conservationists get so excited by their return. It’s not just about a single species recovering — it’s an entire ecosystem coming back to life.

Rather than allowing the sea otter’s return to spark the same controversy as elsewhere, the Council of the Haida Nation, with support from Parks Canada, decided to develop a sea otter management plan — one that would be guided by both traditional knowledge and western science. Boyko says the plan — named Xaayda Gwaay.yaay Kuugaay Gwii Sdiihltl’lxa: The Sea Otters Return to Haida Gwaii — is expected to be completed in late 2024 and will also rely on community input.

It’s a potentially risky move, given the heated debates in other areas. “We lived with sea otters for thousands of years, long before colonization,” says Boyko. “We have a lot of experience co-existing with these animals that we know we could draw on.”

The Pacific Urchin Harvesters Association was one of several stakeholders engaged when the partners began developing the sea otter management plan in 2021. Experts on sea otter ecology were brought in from universities and non-profit organizations to share their knowledge. Other First Nations who already have sea otters in their midst, such as the Nuu-chah-nulth on Vancouver Island, were invited to talk about their experience. A series of “community conversations” were also held over Zoom, to gather input from residents on what the return of sea otters might mean for them.

“We wanted to really acknowledge that it’s complicated; it’s not a one-sided issue for community,” says Niisii Guujaaw, the manager of marine planning with the Council of the Haida Nation, who co-led the community engagement.

Anxieties were understandable. While generational knowledge of the sea otter stretches back far beyond their lifetimes, the current marine environment — as out of balance as it might be — is the only one that today’s residents have ever known. But community feedback was mostly positive, says Guujaaw. There was a high level of awareness that sea otters are ecologically important. People were also keen to restore their cultural relationship with sea otters. Their furs were often worn for traditional ceremonies by chiefs and other high-ranking people who had the technical skills to hunt sea otters. The pelts were also used in day-to-day life as bedding and insulation.

The main lesson the Haida heard from other First Nations? To plan ahead and to draw from their traditional knowledge. “I think the most striking thing was that when sea otters were reintroduced [in the late 1960s and early 1970s], the Nations there weren’t involved in that conversation at all,” says Guujaaw. “They were all in a reactionary position, whereas I think we are better situated to be playing an active and leading role in the management.”

The Haida have always looked to the ocean for their food. Ancestral clam gardens — rock walls built in the intertidal zone to improve shellfish habitat — have been discovered dating back thousands of years. Likewise, studies of archeological middens (buried piles of shells, bones and other waste from Indigenous villages) have shown that shellfish and crabs have long been an important part of the Haida diet.

So how did they peacefully co-exist with sea otters? Evidence including oral history suggests that the animals were hunted, particularly near villages where shellfish foraging would have been most intense.

The hunt wasn’t just open season though. Otter remains in middens show there was a fairly consistent harvest of the animals over time, suggesting their population was carefully maintained. In other words, the sea otter population was managed. “This idea that sea otters were once-upon-a-time untouched, that they just were allowed to roam — we know that’s not true,” says Lee.

Sea otters have been off limits for hunting in Canada since 1911, when the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention was signed. They’re now designated as a “species of special concern” under the Canadian Species at Risk Act (they were down-listed in 2009 from “threatened” status). The idea of hunting them is highly controversial and runs counter to the “hands off” approach that typically guides Western conservation efforts. But the Haida, like many First Nations, see humans as a part of the ecosystem rather than separate from it. Hunting is considered a way of stewarding the environment. “We have an expression that goes like this: ‘Everything depends on everything else,’” Boyko says. “It’s one of the guiding principles of the sea otter management plan.”

The next step in the project will be using a computer model to simulate different management approaches. The model, developed through collaboration among several institutions, including the Council of the Haida Nation, Florida State University and independent consulters Nhydra Consulting, looks at the impact on kelp, urchins and abalone if sea otters were to return to Haida Gwaii without any human interference. Modellers will also test what might happen if a limited hunt is permitted, or if other non-lethal tools are used to deter sea otters from certain areas like important shellfish and abalone habitats. The model will predict how these scenarios might play out over time. Climate change, which is expected to hurt kelp, is also being factored in. The modelling results will then be used to gather more community input. “We’ll bring that information back to the community,” Guujaaw says, “and then start the process of bringing a plan to Haida leadership for direction.”

In some ways, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Haida Gwaii is the place where a high-powered computer model is integrating ancient traditional knowledge. The remote archipelago has long been at the forefront of Indigenous-led conservation. Gwaii Haanas (designated a national park reserve, a marine conservation area and a Haida heritage area) was created in 1993 through an agreement reached between the federal government and the Haida Nation, after Haida-led protests halted logging in the area following decades of clear-cutting. The area has been successfully co-managed by the Haida and Parks Canada ever since, using consensus-based decision-making.

The archipelago still bears the scars of colonization though. After sea otters were extirpated, beaver and deer were introduced by Europeans in the early 1900s for fur and meat, but quickly overran the islands (and remain a problem today). Earlier still, rats arrived on ships and threatened many of the seabirds that make stops here. Commercial fishing has taken a toll on the once-abundant salmon and herring populations. The Haida, in partnership with Parks Canada, have worked to undo some of those harms (rats have been eradicated from several islands).

On the eastern side of Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island), the site of the logging protest that led to Gwaii Haanas’s creation, a 13-metre-tall totem pole faces out to KandaliiGwii (Hecate Strait) and the B.C. mainland. Known as the Legacy Pole, it was erected in 2013 to mark the 20th anniversary of the conservation area. It was the first pole raised in Gwaii Haanas in 130 years. It’s meant to reflect the Haida’s stewardship of this area, from the sea floor to the mountain tops: a sculpin is featured at the base of the pole, and an eagle perches on top. In the middle, five people stand in a line holding hands, representing the logging protesters.

By Lee’s estimate, it will likely be more than 30 to 40 years before sea otters have fully repopulated Haida Gwaii. That timeline gives her hope that their homecoming will be different here than the rocky reception they’ve gotten elsewhere. “We can plan ahead for the return of sea otters, led by the Haida Nation, in a way that considers culture and ecology equally,” she says.

Visitors here sometimes make the mistake of referring to Gwaii Haanas as a national park, something Cindy Boyko is always quick to correct. “It’s not a park,” Boyko says. “It’s our home.” A home now preparing itself for the return of a long-lost family member — appetite and all.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the March/April 2024 Issue

Wildlife

On New Brunswick’s Machias Seal Island, predatory gulls are pushing endangered Arctic tern colonies to the brink, creating a dilemma for wildlife managers

Wildlife

An estimated annual $175-billion business, the illegal trade in wildlife is the world’s fourth-largest criminal enterprise. It stands to radically alter the animal kingdom.

Environment

Two marine biologists offer a glimpse of life at the bottom of the ocean during 2018, 2019 and 2020 seamount expeditions

Environment

The people and landscapes of Haida Gwaii opened my eyes to the fact that we all rely on the ocean