Science & Tech

20 Canadian innovations you should know about

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

- 3327 words

- 14 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

Numerous books have explored the Highland Clearances (the forced mass eviction of tenants from Scotland’s Highlands and western islands, mainly to turn land to sheep pasture), which began around 1760 and lasted a century. Many more have treated the arrival of many of these Highlanders in pre-Confederation Canada, both east and west. Flight of the Highlanders: The Making of Canada, explains Ken McGoogan, an author and Fellow of The Royal Canadian Geographical Society, intertwines the two stories. Half unfolds in Scotland, half in Canada. Those evicted Highlanders who emigrated after being driven from their ancestral homelands were a marginalized minority.

The sad irony is that, in some locations in Canada, these refugees displaced Indigenous peoples whose way of life depended on wilderness and wide-open spaces. The following chapter of the book, “Creating Red River Colony,” sets up the clash between past and future.

After putting the Prince Edward Island colony on a solid footing — listening to settlers, assigning lands, appointing leaders — Thomas Douglas, the fifth earl of Selkirk, decided to write a book advocating emigration to what is now Canada as a solution to domestic problems in Scotland. He proposed to establish a series of distinctive “national settlements” that would protect language and culture, guarding immigrants “from the contagion of American manners.” Each would be “inhabited by Colonists of a different nation, keeping up their original peculiarities and all differing in language from their neighbors in the United States.”

Backed by the Colonial Office, Selkirk chose what looked like a promising location on Lake St. Clair, near the border to the United States in the southwest corner of Upper Canada. He visited the site, which he named Baldoon. He hired a manager and, with the first Highlanders on their way from Scotland, watched construction begin.

Back in Britain, Selkirk began writing a book championing Scottish emigration. In 1805, as he finished it, he heard that Baldoon was faring poorly. By sheer bad luck, he had visited the site during one of the driest seasons in decades. Soon after he left, heavy rains had transformed low-lying areas into swampland, which gave rise to poor crops, illness and even deaths from malaria. So he focused in his book on his successful Prince Edward Island colony, and his considered arguments began altering attitudes about Highland emigration.

The situation in Baldoon went from bad to worse. Fifteen families had arrived in September 1804 — a total of 102 people — only to discover that they were living adjacent to a mosquito-infested swamp. When Selkirk visited, those lands had been high and dry and rich in loamy soil. In choosing the site, he had been thinking strategically. He wanted to set a barrier against American influence. “The Scottish Highland emigrants,” he wrote, “are of all descriptions of people, the most proper for the purpose, since independently in their character and in other respects the very circumstance of their using a different language [Gaelic] would tend to keep them apart from the Americans.

“The emigrants, who in a few years must unavoidably leave Scotland, would be sufficient to form a colony of such force as would render Upper Canada safe from any attack it is likely to be exposed to and to be an effectual check on the disaffected French of the Lower Province.”

Within two months of reaching Baldoon, sixteen settlers had died, including five heads of family. But against all odds, the remaining Highlanders made progress. They moved a short distance to another part of the land grant, built houses and planted crops. Eventually, the settlement would thrive. But in 1809, it looked like a failure. Chastened by that, and discerning that the clique controlling Upper Canada wanted no rivals, Selkirk began speculating about settling an area farther west.

Several years before, in Voyages through the Continent of North America by Alexander Mackenzie, Lord Selkirk had read that fertile lands existed in the Red River district controlled by the HBC. Having recently married Jean Wedderburn, an intelligent, courageous woman fifteen years younger, Selkirk now found a powerful ally in her brother. With Andrew Wedderburn, Selkirk began buying shares in the Hudson’s Bay Company. He had realized that to colonize the west, he would need to work in concert with fur traders. But he underestimated the challenges and failed to appreciate that by bringing settlers into the northwest, he would directly threaten an economy, a way of life and, indeed, a distinct people who had evolved out of the fur trade.

By late 1810, together with his brother-in-law, Selkirk owned enough shares to control the HBC. But the fur trade was in competitive crisis as a result of the over-harvesting of beaver. To strengthen the HBC, Andrew Wedderburn had started recruiting Highlanders from the western islands of Scotland, offering them land in exchange for three years of service. When the North West Company approached the HBC with a plan to reduce increasing tensions by partitioning the fur trade, Selkirk rejected the proposal. He intended to leverage the HBC’s 1670 charter, which granted a monopoly over all the lands draining into Hudson Bay.

Selkirk dusted off an old proposal to develop the fertile Red River area as a settlement for retired fur traders. He would not stop there. He proposed to create a substantial colony, the first in a string that would extend across the west. In March 1811, he cut a deal with the Hudson’s Bay Company. In exchange for financing and founding a settlement at Red River, Selkirk would gain control of 116,000 square miles (300,000 km2) of land — an area five times the size of Scotland.

Some denounced this Red River Settlement as madness. The place was too deep in the wilderness. But Selkirk saw Red River as resolving three major challenges. It would lay the foundations of a faithful British colony west of Upper Canada. It would address the deteriorating situation in Scotland caused by the Highland Clearances. And it would provide a buffer against the expansion of the American colonies. He saw Red River Settlement as becoming his greatest legacy, the product of all that he had learned from his colonies at Baldoon and Belfast (Prince Edward Island).

But Selkirk had a blind spot. He failed to see that helping the refugee Highlanders would mean displacing another people — the Bois-Brûlés or Métis. Their economy relied on hunting and the fur trade. Selkirk meant to build a world around farming. Conflict was inevitable.

The partners in the North West Company had no such blind spot. They saw immediately that Selkirk’s Settlement would strain the region’s resources, interfere with their Athabasca fur-trade route, and decimate their profits. In Britain, they mobilized too late to block the deal. But they did not regard the battle as lost. During the next decade, Red River would become the centre of an epic struggle in which past met future.

By the early 1800s, almost 5,000 voyageurs worked in the Quebec-based fur trade. They paddled the rivers and lakes between Montreal and the North Country. Most of them were French Canadians and many had married Indigenous women à la façon du pays and fathered children. Those offspring, born into the fur trade, called themselves the Bois-Brûlés (Burnt-Wood People). As Selkirk’s plan took shape, their resistance would grow and spawn the politically conscious Métis nation.

Here we discover a great irony. Refugees arriving from the Highlands and Islands, driven out of their own homeland, were destined to get caught in a crossfire. The Highlanders, displaced from their ancestral homes, were unwittingly caught up in displacing a people as innocent as themselves of schemes and machinations — but equally committed to fighting for the way of life into which they had been born.

In 1811, Selkirk appointed the ill-prepared Miles Macdonell first governor of Assiniboia, which comprised all territory within 80 kilometres of the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Born into a distinguished Roman Catholic family in Inverness in 1767, Macdonell had sailed at age six on the same ship, the Pearl, as the parents of Simon Fraser. Having retreated north during the American Revolution to Glengarry County, Macdonnell had impressed Selkirk as a well-mannered gentleman who “could get work done when nobody else could.”

Macdonnell set out for Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis to collect about 100 recruits gathered from far and wide. The transport ships did not reach their destination until July 17. The recruits had arrived weeks earlier, and when they weren’t drinking, fighting, or grumbling, they had time to fret over a dark, destructive article that appeared in the Inverness Journal.

Written by an anonymous Highlander — in fact, Simon McGillivray of the North West Company — it warned recruits that they faced a hazardous voyage, an extreme climate, and a hostile reception: “Even if they escape the scalping knife, they will be subject to constant alarm and terror. Their habitations, their crops, their cattle will be destroyed and they will find it impossible to exist in the country.” Small wonder that some men bailed at the last moment, leaping overboard and swimming ashore.

Customs officials, probably bribed by the North West Company, delayed departure on technicalities. They refused to let the livestock on board, alleging that the old ship could not carry enough water. Finally, on July 26, 1811, the Edward and Ann sailed for Hudson Bay. The voyage, hampered by headwinds and storms, lasted an interminable 61 days. The ship reached York Factory on September 24, so late in the season that nobody could then set out for Red River, 1,124 kilometres away.

At York Factory, the superintendent of the HBC’s Northern Department, a veteran fur trader named William Auld, demonstrated his determined opposition to the colony. He sent the settlers 37 kilometres up the Nelson River to spend six or seven cold, dark winter months in freezing log huts. Food grew scarce and Miles Macdonell struggled to control the men. A riot led to the jailing of two men (later sent back to London); an armed insurrection culminated in the departure of nine more men; and an outbreak of scurvy cost one man his life. The river ice lingered and Macdonell couldn’t break camp until June 22, 1812 — nine months after arriving.

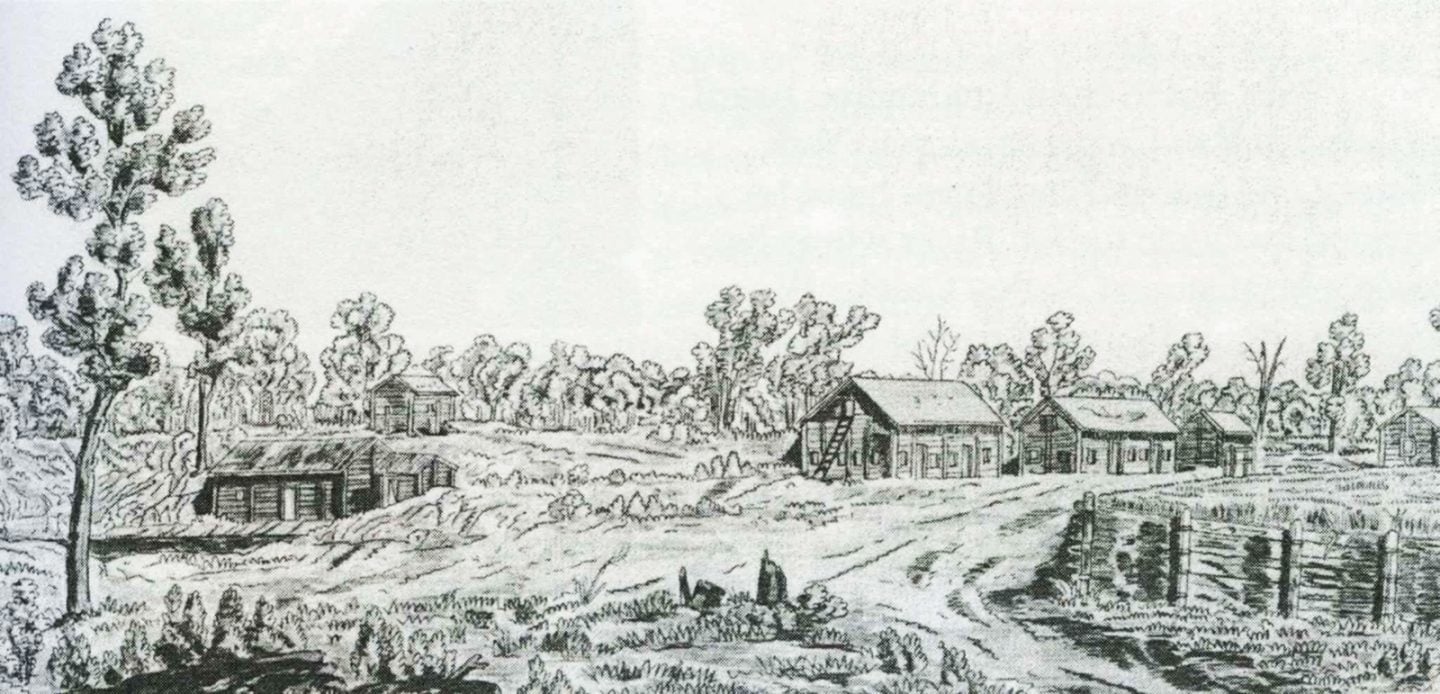

He started up the Hayes River with an advance party of twenty-one workmen, determined, as he wrote Selkirk, to “take possession of the tract and hoist the Standard.” They reached their destination, the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, on August 30, 1812. Historian Vera Kelsy describes them as arriving “footsore, weather-beaten, mosquito and black-fly bitten” — and to no enthusiastic welcome. There, at The Forks in present-day Winnipeg, they set to work building Fort Douglas, headquarters of the Red River Colony.

Now the challenges came thick and fast. Macdonell had to secure a steady supply of food for the anticipated settlers and to establish friendly relations with people living in the vicinity — local representatives of the rival fur-trading companies, as well as First Nations and Bois-Brûlés. These last spent a lot of time in this area hunting buffalo, from which they derived pemmican, the staple food of the fur trade. It was a concentrated, portable, high-protein mixture of pounded meat, fat or grease, fruits and berries. Any trader heading out onto the rivers carried pemmican.

Having arrived too late in the season to do more than begin building a settlement, Macdonell sent most of his men 115 kilometres south to build the smaller Fort Daer at Pembina, which was part of the Selkirk territory, but is today just across the border in the United States. He continued clearing and preparing the site for Fort Douglas, slated to be a landmark edifice at 17 metres by 6.5 metres. In October, when the snows began to fly, he too proceeded south.

Miles Macdonell had brought builders and carpenters. Late in October, the first contingent of settlers — men, women and children, some of them sick — arrived at Pembina. Seventy people, hailing originally from Ireland and the Scottish Hebrides, had sailed from Sligo on June 24 aboard the Robert Taylor. Their promised houses had yet to be built. Macdonnell brought some of the women and children into the emerging Fort Daer and billeted some families among friendly First Nations.

At Pembina, the Bois-Brûlés, too, welcomed the newcomers. According to Métis historian Richard D. Garneau, Charles Peltier led the immigrants to land cleared and ready for cultivation. He provided horses and carts to build Fort Daer — so named after Selkirk’s late older brother, Lord Daer — and then lent his cart and canoe to an immigrant family.

Baptiste Roy took care of the immigrants’ seed grain. François Delorme and his son supervised the building of family houses. Jean-Baptiste Lagimodiere, a French “freeman” or freelance voyageur, led a hunting party of fifteen Bois-Brûlés, among them Bostonnais Pangman, to secure food for the Scots. A hunter named Isham, probably the son of well-known HBC man James Isham, supervised the breaking of soil and became chief interpreter, while his son worked as a hunter for the newcomers. Initially, then, relations were friendly, even convivial.

The ensuing winter brought hardship, misery, and hunger. Historian Samuel H. Wilcocke quoted from an on-location letter: “Take a view of the state of one family, and it will show you what the sufferings are of these people: an old Highlander, his wife, and five children, the youngest eight or nine years of age, poor, and consequently badly provided with clothing to encounter the rigors of the climate, where the hottest summer never thaws the ground to any considerable depth — see this family, sitting on the damp ground, freezing for want of sufficient covering, pinched and famishing for want of food; and the poor woman had to take the well-worn rug from her own miserable pallet, to sell for a little oat-meal to give her dying children, and in vain, for two of them did not survive this scene of misery.”

During a buffalo hunt, the new-comers took on the difficult task of hauling meat back to camp. This they did, a Nor’Wester reported, “destitute of all necessities, such as snow-shoes, caps, mittens, leather or blanket coats, socks, kettles, fire-steel or flint.” Not only that, but “some of these wretches, for want of the means of making a fire, have buried themselves in banks of snow to prevent their being frozen to death, and have often been forced to eat the raw meat off their sledges.”

In June 1814, after an extremely difficult journey, a second wave of settlers arrived at the Forks. They had been evicted from Kildonan in Sutherland, Scotland. Estimates differ, but historian George Bryce suggests that by year end, the total number of settlers in the vicinity was 180 or 200. Men were still building Fort Douglas. The newcomers went to work with a will, clearing small farms to run in long, narrow strips back from the Red River. Only now, after arriving at the Forks, did they learn that in January, Miles Macdonnell had issued a recklessly dangerous proclamation forbidding the export of pemmican from the HBC territory. But neither they nor their fellow Highlanders yet realized that their New World trials had scarcely begun.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Wildlife

Canada jays thrive in the cold. The life’s work of one biologist gives us clues as to how they’ll fare in a hotter world.

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe