People & Culture

The funniest places: Why Canadian comedy is obsessed with geography

From Letterkenny to Schitt’s Creek, Canada’s geography has become the laughing stock of television — and that shouldn’t come as a surprise

- 1583 words

- 7 minutes

Travel

Prince Edward Island's answer to the famed Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route in Spain, the Island Walk is a lesser known (for now) 700-kilometre journey that circumnavigates the island

Anxious and frustrated. It’s not exactly the state of mind I was aiming for as I start out on the Island Walk, Prince Edward Island’s newest tourist attraction. Dale Larkin and I have spent 15 minutes driving around the town of Kensington searching for waypoint 15 of the Island Walk, a 700-kilometre route around the island. The route is divided into 32 segments, each walkable in a single day and all but one logging in between 19 and 27 kilometres. Larkin owns Inn at the Pier in Stanley Bridge, my destination today and my starting point for the next trail segment tomorrow. This is the walk’s first full year and I’m Larkin’s first customer; it’s almost noon and I’ve not yet started my trek back to the inn.

In 2021, the walk is so new that not all the directional signs are in place — Number 15 might be one of them. We finally find it in the middle of a small park. Larkin gives me his phone number and returns to the inn. Across from Kensington’s restored train station, I grab a coffee from The Willow Bakery & Café and, feeling rushed but relieved, head out at last on the Confederation Trail, some of which forms part of the Island Walk. I can only hope I’m setting out in the right direction.

The Island Walk, or the Camino de la Isla, was conceived by Bryson Guptill. He came up with the idea after he and his partner walked the 800-kilometre Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route in Spain in 2016 and Portugal’s Rota Vicentina three years later. Guptill helped develop the 150-kilometre-long International Appalachian Trail in P.E.I. and walked it as preparation for his Camino de Santiago trek. With help from other members of the Prince Edward Island Trails organization, he researched, designed, mapped and walked every step of P.E.I.’s camino.

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of Galicia in northern Spain, where it’s said the remains of the apostle Saint James are buried at the cathedral. P.E.I.’s Island Walk has no religious significance, but the brochure created to promote it promises to “transport you to an uncomplicated time. To escape the mayhem of modern life. To discover a humbling place — its wildlife, its culture and its people. To come back different.”

As practical as he is philosophical, Guptill wrote a guidebook to the walk in which he claims the loop design is an advantage. Walkers can begin and end anywhere along the route, and they don’t have to transport all their belongings to an end point.

I selected segments 15-16 and 16-17 for a two-day mini-Camino, thinking they would be a good sample of what a walker might expect if they took on the full circuit. These segments are in the middle of the province. The first passes through popular tourist areas known for, among other things, several Anne of Green Gables sites. In contrast, the second segment heads to the coast along the quiet hiking trails and beaches of Prince Edward Island National Park.

Half an hour out of Kensington, and some friendly Islanders confirm my growing suspicion — I’m walking in the wrong direction. By the time I return to Kensington, I’ve already walked six kilometres and I’m feeling it, both physically and emotionally. I curse my incompetence. The day is practically a write-off. I come to think of Guptill’s promises of escape as unattainable. What is walking, after all, but a way to get somewhere too slowly?

On the right road at last, settle into a rhythm. Cars and giant farm machinery pass, but traffic is light. Walking between fields of late summer crops — corn, wheat, soybeans — I begin to notice details. Crickets chirp. Caterpillars undulate over gravel. A crow perched on a wire follows my progress. I say hello, but it neither responds nor flies away. I pause to pluck a stock of wheat and weave it into my straw hat.

Before I know it, I’ve covered a lot of ground. At a crossroads, I choose a shortcut to make up for the extra kilometres I walked at the day’s outset. It leads down one of those iconic P.E.I. red dirt roads. In the distance, a blue inlet pushes into green fields. Many P.E.I. roads are surprisingly straight, and I find myself looking far ahead, knowing that these hilltops and intersections in the distance are places I will eventually be.

On Route 6, I see a chance for another detour onto a quiet gravel road. At the intersection, I stop at a house where a woman is working in her garden to ask if the road loops back to Route 6. With typical Island friendliness, Ruth Henderson introduces herself and asks what I’m up to. It turns out she walked half the Camino de Santiago in 2018, using another of Bryson Guptill’s guidebooks.

“I met Bryson a couple of years back,” she says. “When he and his crew went on the pre-walk, I joined them on two occasions. I think it’s an amazing thing to have on P.E.I. You’re the first person I’ve met who’s walking it.” She confirms that the detour is, indeed, a nice, scenic loop.

It’s along this quiet road that I begin to pay attention to my body, noticing human needs and physical sensations like tiring legs and aching joints. Hunger and thirst are easily subdued with snacks and drinks, but pains and fatigue grow more acute. Over all of this, I begin to feel the rhythm of my breath. I have a sense of myself as a living, breathing animal, conscious of moving through the world. My background in literature has me thinking how, from the quest of Homer’s Odyssey to the pilgrimage of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, physical journeys have long stood in for life journeys.

Back on Route 6, the traffic is heavy and fast. I haven’t escaped modern life. Quite the opposite. Part of the teaching today is that I live with so many other people, all of us hurrying through a world dominated by noisy machines. But somehow, without trying, walking has brought me the time for reflection and peace that Guptill anticipated. Even as I notice the way my thoughts are effortlessly stringing into narratives, I suddenly become aware that my feet are still moving. The self-doubt and frustrations I suffered earlier have disappeared.

The next morning, Bryson Guptill joins me to walk the next segment, which includes the paved, coastal trail through Prince Edward Island National Park. Guptill is in his 70s and carries the smallest of backpacks. Even as the day becomes uncomfortably hot, he walks at a steady pace and drinks little water.

We fall into conversation about the Spanish Camino. Nearly 350,000 people walked it in 2019, including about 5,300 Canadians. “About 10 per cent are real pilgrims,” Guptill estimates. “Others are interested in the spiritual aspect of walking and contemplating. But most are doing it because something changed in their life. Maybe they retired or broke up with their partner. What I find remarkable about the Camino is that people do it a number of times. It becomes an obsession.”

Guptill sees practical links between the Spanish and P.E.I. walks. The Spanish Camino has an active group in Canada called the Canadian Company of Pilgrims that supports Canadians interested in the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Membership is at 2,100, with chapters in most provinces. “I’ve given Zoom talks to five chapters. They’re mostly focused on the Camino de Santiago, but this would be a good training run.”

On the Island Walk Facebook page, I discovered a group of seven walkers from Ottawa, some from the local chapter of the Canadian Company of Pilgrims. Paul Hughes formed the group in the winter of 2020-21. Most are in their 60s. All are retired. Of the five women and two men, most have walked the Spanish Camino, some several times. One has walked the Portuguese Camino five times. Hughes himself has walked pilgrimages in Spain, Portugal, France and England. “We’d be in Europe, but we’re looking at the COVID numbers,” Hughes told me.

On September 5, 2021, they set out from Charlottetown with the intention of completing the entire circuit by mid-October. When I asked about motivations, he said, “There was an interest in P.E.I. as a recognized tourist area. There’s that sense of achievement in completing this. I don’t think there’s anybody in the group with a religious motivation.”

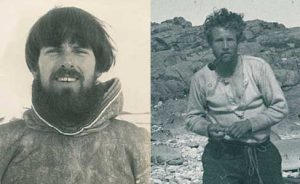

Guptill’s own fondness for long-distance walking is rooted in his childhood. His father worked first as a preacher, then as a doctor. His double calling eventually led the family from Nova Scotia to New Brunswick, where he worked in the town of Dorchester and at the infamous penitentiary there. Later, the family moved to a remote New Brunswick farmhouse.

“There was no bus transportation, so it was a long, long walk in all weather,” Guptill recalls. “It’s really etched in my brain.” Like his father, Guptill pursues spiritual and physical wellbeing and is keen to give back to his community. “The Walk is something to help the common good. There’s something about the experience — the contemplation, the serenity, some spiritual attachment to the outdoors. To stay healthy, something compels us to move. It’s good for our heads, as well as our hearts. You can do it anywhere. You don’t need equipment. You can just walk.”

By the time we arrive in North Rustico for lunch, it’s too hot to continue. Over cold beers, we talk about Guptill’s hopes for the future. He’s helped raise funds to contract a management company that’s guiding the Island Walk to completion, including installing directional signage across P.E.I. Once that’s done, he expects the walk to take on a life of its own. I head back to the inn with a taste for more long-distance walking; I realize I’m hooked. Even my short walk has left me with a sense that if I just let things be, I will eventually get where I’m going.

I call Guptill and tell him I feel compelled to return sometime to walk all 32 segments. He says, “I understand.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

From Letterkenny to Schitt’s Creek, Canada’s geography has become the laughing stock of television — and that shouldn’t come as a surprise

Wildlife

Salmon runs are failing and grizzlies seem to be on the move in the islands between mainland B.C. and northern Vancouver Island. What’s going on in the Broughton Archipelago?

Mapping

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps

Science & Tech

In the fall of 1947 Tom and Jackie Manning decided their dinner table was too small. The experienced Arctic travellers couldn’t seat any more of the guests who often gathered…