Spanish chestnut (Castanea sativa). Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé’s Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany. Public Domain image / Wikimedia Commons.

The Spanish chestnut (Castanea sativa), the species I encountered on my journey, comes from southern Europe and western Asia. It is a gorgeous and fast-growing tree that reaches sixty feet. The delicious nuts are considered a delicacy. Many hybrids have been developed. These are the chestnuts of commerce, with ‘Colossal,’ ‘Nevada,’ and ‘Schrader’ being the best-known cultivars. They produce larger nuts than either of their parents, and they are also more vigorous and produce bigger crops. They are sometimes planted as ornamentals, and their brilliant yellow fall colour is quite beautiful.

Chestnuts are very nutritious and are peculiar in being the only nuts known to contain vitamin C; they are also self-sterile, incapable of pollinating their own blossoms. To obtain a crop, two trees must be grown reasonably close together. Sicily is currently the world’s leading supplier of chestnuts, but France and Portugal also produce a large quantity.

The horse chestnuts (Aesculus) and their American relations, the buckeyes, are not related to the true chestnuts. The common name is a corruption of “coarse” chestnut, and they were so called to distinguish them from sweet chestnuts. No species in this genus produces edible nuts. These are slow-growing, wide-spreading trees that can reach significant sizes and are found in nearly every major city in Europe. They cast a heavy shade and are ideal for front yards or parks. Their candle-like flower clusters in the spring are very ornamental, and their large, stone-like reddish brown seeds cover streets and sidewalks in the fall. All have beautiful foliage: the leaves are divided into numerous leaflets, somewhat resembling a hand. The seedpods are prickly and split open when fully ripe to reveal shiny, smooth, rather beautiful seeds. (Squirrels will eat these; humans will not.) The prickly husks are painful if stepped on in bare feet, and the British know them as “conkers.” All of these trees are easy to cultivate, but they do grow from a taproot and are very cranky about being disturbed. They are prone to suffering long bouts of transplant shock and should be planted as small as possible, ideally as seed. Sowing the fresh seed in fall generally results in germination the following spring.

A rich, fertile soil with good moisture conditions will suit them, though they are extremely drought-tolerant once established. Furthermore, they are very prone to windburn, particularly when young, and if at all possible should be planted in a sheltered site. Horse chestnuts are often the last trees to leaf out in the spring and are not subject to pests or disease, and they rarely need any pruning. They are much planted on both the east and west coasts but little seen on the prairies.

By far the hardiest species in the family are the European horse chestnut (A. hippocastanum) and the Ohio buckeye (A. glabra). European horse chestnut is officially hardy to zone 4. It can reach sixty feet in height and is native mainly to Albania and northern Greece at high elevations. The cream-coloured to ivory flowers are produced in great profusion, then comes a huge crop of the famously inedible nuts. Although this species is not well suited to the prairies, mature and stunning examples of these trees can be found in Edmonton, Camrose, and Calgary. In most cases, they were grown from seed and nurtured and pampered until they were able to adapt to the climate.

Ohio buckeye is the state tree of Ohio, and as the name implies, it is native to central and eastern North America. It can grow into a very large tree of fifty to sixty feet, but it is slow growing and infrequently planted. The large leaves are quite splendid and although the blossoms are not as showy or profuse as A. hippocastanum, they are still certainly attractive. The large clusters of seeds that follow provide food for squirrels and deer. The seed is an enormous roundish ball that ranges from reddish brown to dark brown. It is encased in a prickly husk about the size of a walnut, and as they ripen, the husks start to break open, revealing the large, shiny seed inside. With a little imagination, one could imagine it was the dark-brown eye of a deer peering out at you, hence the common name of buckeye. The seeds are so smooth and polished-looking that I keep a bowl of them here on my desk just to be decorative. Sometimes I pick them up and marvel at their beauty. The trees’ fall colour is highly variable: yellow is the usual, but orange and red are not unheard of, and some years they produce no bright fall colour at all. Both of these trees are easily grown from fresh seed sown in the fall, and mature specimens exist in Saskatoon, Regina, Calgary, and Edmonton.

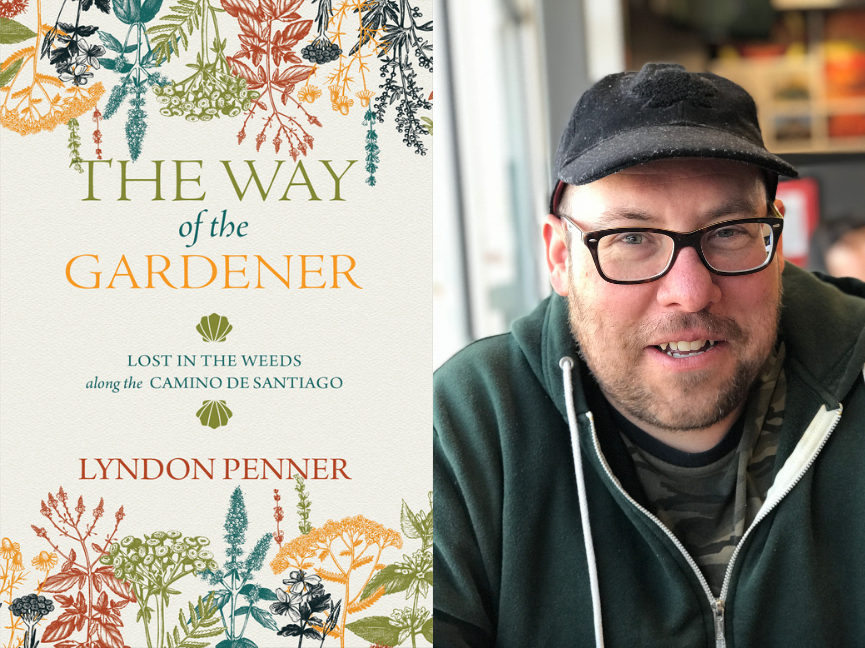

Lyndon Penner has worked as a radio gardening columnist, horticultural consultant, and professional landscape designer and has been gardening since the age of three. He appears frequently as a guest speaker at universities, colleges, and gardening associations in western Canada and is the author of several gardening books.

Excerpt of The Way Of The Gardener Copyright © 2021 Lyndon Penner, excerpted with permission of University of Regina Press.