Exploration

Canadian Space Agency astronaut profiles

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

- 1067 words

- 5 minutes

Science & Tech

As the son of a meteorite curator and children’s librarian, Chris Herd’s childhood was filled with reading science fiction books from his mother and watching his father work with meteorites. Fusing these two interests and influences together at age 13, Herd says he realized a passion that he would then chase for years to come.

“I said, ‘I want to be there when they bring samples back from Mars,’” he explains. “So it’s been something of a lifelong goal of mine to be involved in the process.”

On Feb. 20, Herd was selected as one of the 10 returned sample scientists from across the world for the first-ever NASA mission to bring rock samples from Mars back to Earth.

“I was reading the letter and I said, ‘This is it. I made it. I’m in,’” he says. “I was floored — I couldn’t wait to tell people.”

Working as a professor and curator of the meteorite collection at the University of Alberta, Herd’s expertise is in planetary geology. In addition to being the only Canadian returned sample scientist for the Mars rover mission, he was also chosen to be one of the two representatives on the project science group, responsible for making critical decisions for the mission.

Herd has studied meteorites for 20 years, particularly those that have come from the surface of the red planet, but the mission to Mars work is something no one has ever done before.

“Collectively, as space agencies, we’ve done a lot of exploration of Mars and about 10 to 15 years ago, it was identified that Mars sample return is the next big thing,” he says, adding that there have been limitations to studying the 132 identified Martian meteorite samples. Almost all are igneous rocks from lava, and only the strongest samples survive the trip to Earth as meteorites. As these younger samples do not contain rich organic material such as possible microfossils, they offer a limited picture of Mars’ history.

“We don’t have anything in the meteorite collection that is old enough or the right type to really answer the question of if life was there,” Herd explains. He says because this mission will investigate whether there is organic matter in the rock samples, it could point to evidence of past life on Mars.

After landing on Mars in February 2021, the rover will collect samples for three years. During this time, the team of 10 scientists will decide which rocks the rover will collect samples from. The samples will be about 10 centimetres long, sealed in a sleeve and then left on Mars to bring back to Earth when the time comes.

Choosing the best possible site on Mars to collect these samples took a few years to decide, Herd says. NASA ended up settling on the Jezero crater, which was filled with water about four billion years ago and now contains solidified sediments.

“Mars has a really interesting history that involves being warm and wet in its first billion years of history, and then going through this transition,” he explains. “The atmosphere got thinner, it cooled off, the water got more acidic, and we don’t really know why that happened. It’s a huge mystery.”

Investigating this mystery, Herd says, is the driving force behind the whole mission.

“One of the things we want to do is look at evidence prior to that climatic change, to look at rocks that existed in a time where we think life might have been able to survive,” he says. “So essentially unraveling the history of that area, and by inference, the history of Mars with these samples.”

By studying samples from the Jezero crater, the scientists will be able to collect samples far older than the meteorite samples that have been studied up to this point.

Like the samples from the moon that were collected between 1969 and 1972, Herd says the plan is to curate the Mars samples carefully and preserve them indefinitely so other scientists can work on them for years to come — though he notes that the samples likely won’t be retrieved from Mars and returned to Earth until around 2031.

“To get a definitive answer of whether there was life on Mars, you have to have the samples back in labs on the Earth,” he says. “Extraordinary claims need extraordinary evidence.”

From rovers and other orbiters, scientists have been able to learn a lot about Mars and its overarching history, understanding the general climate shift. But now, scientists will have deeper insight into the makeup of Mars’ environment billions of years ago.

“We have this framework and picture about how Mars changed over time, but this is going to give us unprecedented resolution about that picture,” says Herd.

And to the boy who grew up reading sci-fi and watching his father work with meteorites, Herd says he’d give this advice: “Hang in there. You like science fiction but you are going to get involved in something that is beyond anything that anyone has ever dreamed of.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

Science & Tech

The last megathrust earthquake to strike Canada was in 1700, and the clock is ticking. How we’re preparing for the impact.

Science & Tech

For scientists and northern lights rubberneckers, 2013 promises to be a once-in-a-decade opportunity to experience the sun’s magnetic power at its height.

Science & Tech

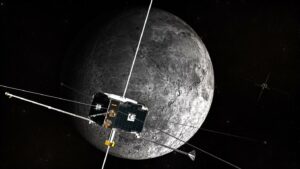

Hansen will be part of the NASA crew for Artemis II, which will see the astronauts spending up to three weeks on a flyby trip to the moon in 2024