Had to make two portages past impossible jams. Next day got past Rouseau L. & out into a great treeless swamp where had to carry wood in canoe to cook. Slept on a mud bank in same where no place to put up tent. Rain & wind before morning. Got thorough ducking. Crept under Canoe.

One can only imagine how Anna Dawson might have reacted after reading in her brother George’s letter of August 1873 this description of his recent canoe journey from Lake of the Woods, Ont., to Dufferin, a base for the British North American Boundary Commission on the southern reaches of Manitoba’s Red River.

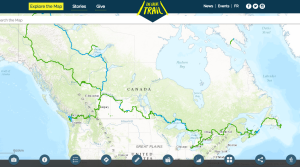

Was she horrified that her brother, whose map of the route is pictured here, was slogging through the wilds of a young province that was still very much a frontier? Amused that he had to shelter under a canoe? Or perhaps proud that he, at just 24 and with a childhood illness that had stunted his growth (he was four-foot-six), curved his spine and left him with chronic headaches, was helping delineate a nation?

During the two years he spent as a geologist and naturalist with the commission, which was marking the 49th parallel and surveying the lands along it for their resource potential, Dawson collected details on a nearly 1,300-kilometre portion of the boundary that stretched from Ontario’s western border to British Columbia’s Rocky Mountains. He spent part of that time operating out of Dufferin, which later became Fort Dufferin, a National Historic Site of Canada that’s along the Crow Wing Trail section of The Great Trail.

In 1875, Dawson submitted his Report on the geology and resources of the region in the vicinity of the forty-ninth parallel, from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains to the commission’s chief, Donald Cameron, with whom he’d worked at Dufferin and who painted the watercolour shown below, believed to depict the region: