Wildlife

Our fascination with mammoths

How the legacy of these woolly giants persists in pop culture, storytelling, ecology and even the controversial idea of de-extinction

- 5019 words

- 21 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Paleontologists in Yukon are working to solve one of the North’s great mysteries — the reason for the major extinction of large mammals at the end of the last ice age — and gold miners and Indigenous hunters are helping gather the clues.

Yukon lay beyond the reach of the massive glaciers that covered most of Canada at various times during the Pleistocene era, which lasted from 2.5 million to 12,000 years ago, and a rich diversity of large mammals — horses, woolly mammoths, ground sloths, lions, camels and other exotic animals — thrived on the territory’s tundra landscape.

Today their bones lie preserved in the permafrost, but there’s no need for paleontologists to go digging for them. Around Dawson, miners who search for gold in stream beds are constantly unearthing fossils, and Yukon paleontologist Grant Zazula and his colleagues have only to travel the back roads every summer to visit the miners and collect what they’ve found — around 6,000 fossils each year. In Old Crow, another paleontological hot spot, the people of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation are experts at finding and identifying bones exposed by eroding riverbanks, and play a prominent role in the research.

Genetic analysis allows Zazula to discover the relationships between animals and how their populations changed over time. Permafrost preserves DNA, and information can be coaxed from the tiniest of samples — from where an animal urinated, for instance, or from microscopic organisms. “With a chunk of frozen sediment,” says Zazula, “you can identify the presence of all kinds of different animal and plant species. It’s remarkable.”

So what caused the extinctions? A series of climate changes is part of the puzzle. During warm periods, camels, ground sloths, American mastodons and other warm-climate animals migrated north to the Arctic, but died out when the climate cooled again.

The arrival of competition from Asia may be another factor. When bison crossed the Bering land bridge to North America about 150,000 years ago, they made themselves at home. Their population skyrocketed and, says Zazula, “they basically kicked everyone else out. Other large herbivores, such as horses and mammoths, just couldn’t compete — and we know bison survived the end of the ice age.” With the other large herbivores out of the way, caribou, which weren’t abundant during the Pleistocene, went on to become the North’s dominant large land mammal.

Researchers are still searching for conclusive answers about what caused all those animals to go extinct, but it’s not just about extinction. “Some species were given new opportunities to thrive and form big populations,” says Zazula. “And what we’re discovering about how today’s northern mammals and environments came to be helps us understand changes we’re seeing now in animal and plant communities as climate change brings warmer winters to the Yukon.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Wildlife

How the legacy of these woolly giants persists in pop culture, storytelling, ecology and even the controversial idea of de-extinction

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Science & Tech

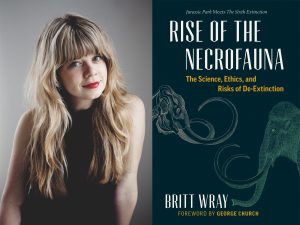

In her new book, Rise of the Necrofauna, Britt Wray examines the science, controversy and ethics of de-extinction, a movement that could one day see the return of extinct species such as the woolly mammoth and Tasmanian tiger