Should we bring back animals that have gone extinct?

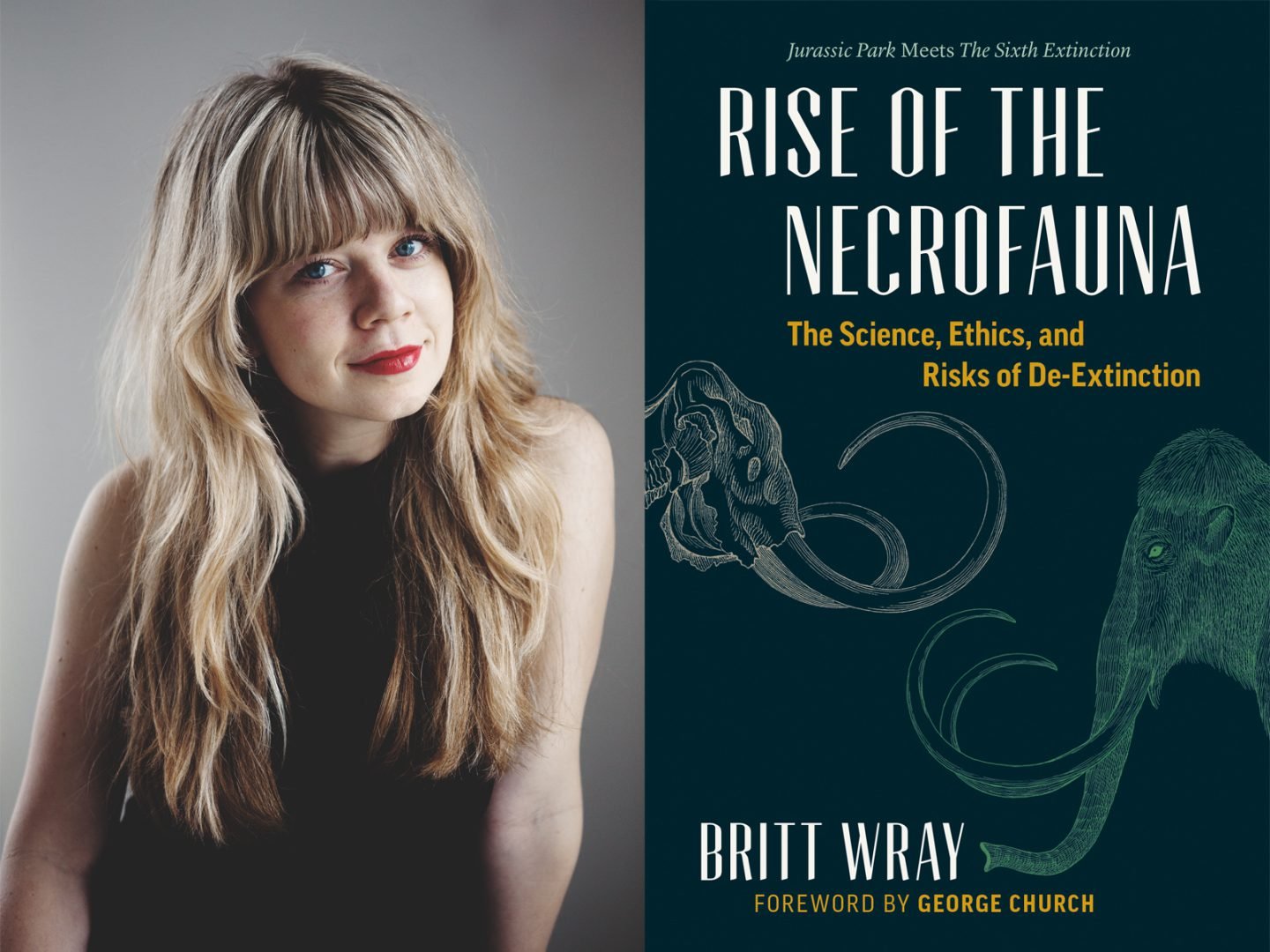

It’s a provocative question that’s rife with ethical and scientific considerations, and one which Britt Wray explores in her first book, Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics, and Risks of De-extinction. Wray, who is a science writer, radio broadcaster and documentarist, takes readers around the world as she speaks with futurists, scientists and philosophers on the topic of de-extinction, an emerging field of science that aims to see versions of extinct species such as the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth inhabit the planet again. Canadian Geographic spoke with Wray about the book, which is available September 30.

On the meaning of necrofauna

It’s a made-up term that I first heard used by a futurist named Alex Steffen, who was using it at a dinner party with a bunch of de-extinction researchers and advocates. He kept asking them if the de-extinction movement might create charismatic necrofauna — by which he meant once-dead animals that people would choose to make unextinct because they find them cuddly or cute or anthropomorphic. So here is a huge ethical issue right from the get go: what are we going to galvanize our efforts around? And will we not just repeat the dangerous choices that we sometimes make when we’re working with endangered species? Necrofauna is a term that hints to some of the issues that are inherent to the practice of de-extinction.

On misconceptions of what de-extinction is

We cannot bring back a true identical carbon copy, in all of its macrobiotic, nuclear, mitochondrial, genetic, environmental forms. We just can’t reproduce that whole package. But de-extinction isn’t about bringing back exact copies; it’s about creating a functional proxy of an extinct species, getting as close as you can to what you want to restore.

On the biggest highlight of researching the book

It was amazing to be able to go to Kenya and see the last surviving members of the northern white rhino population. The fact that I could go right up to Sudan [the last male northern white rhino] and hug him blew my mind. To be near him, to know how important he is, was powerful, sad and inspiring. Just looking at the emotions that kind of situation evokes in people is a huge part of the de-extinction story and how passionately people on both the pro and con side feel.

On what she hopes the book will accomplish

My hope is for conversation and discussion among regular people, because it’s not just a topic for specialists. But by writing this book, have I laid down the welcome mat? Some people I’ve met have said that it’s dangerous to write a book about de-extinction. I think they’re saying that because they feel so adamantly that it’s a terrible avenue to choose if we’re thinking seriously about the sixth mass extinction and the ways in which we should be innovative about conservation. They say, “Don’t invest energy into popularizing it,” which I think is a sentiment that has so many fraught elements. I decided to do it anyway because the world doesn’t stop if I don’t write a book! This is happening, and there are powerful, interesting, fascinating people who are a part of it. I’m not out to tell people de-extinction is wrong or right — I just want people to think for themselves and shed light on de-extinction science.