Let Paolo Forlani’s legacy be a lesson to modern-day artisans: if you want your work to have a lasting impact, large-scale distribution trumps originality.

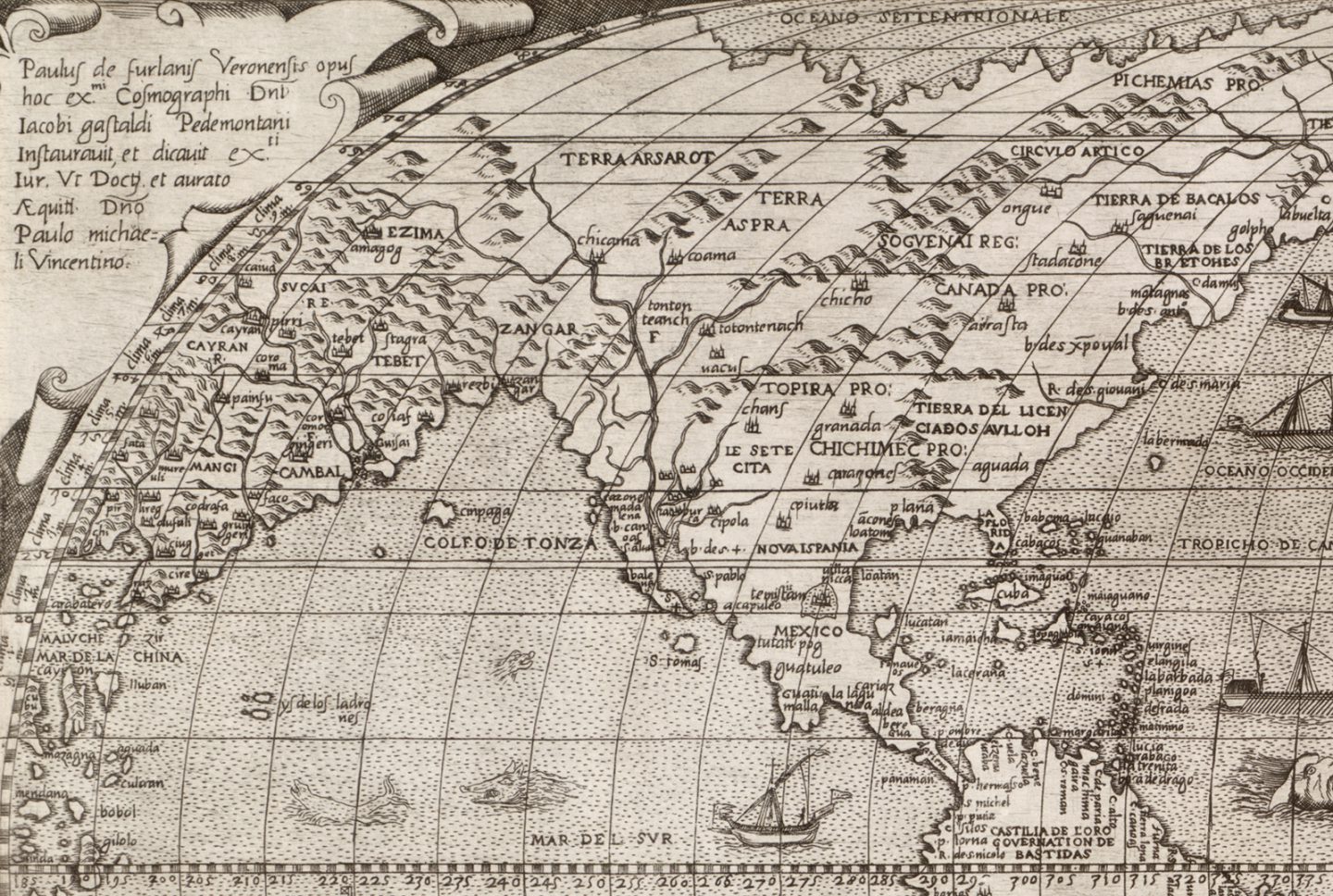

That strategy worked well for Forlani, at least, the Italian map engraver whose 1560 depiction of the world (a portion of which is shown here) is the first known instance of the name “Canada” appearing on a printed map. Others had used the name on manuscripts that most never would have seen, but Forlani ensured the idea of a place called Canada made its way around Europe and beyond.

Forlani worked in Venice during its heyday as the map-making centre of the Western world, and while he was much sought after for his engraving skills, he was also good at compiling the unpublished works of others into printed maps for sale. With the Age of Exploration in full swing, map-making was big business — the cargo of one Dutch ship trading in Southeast Asia in 1602 included 5,000 maps — and merchants travelling all over Europe bought Forlani’s works, many of which ended up in collections across the continent.

Forlani based this map on one created by fellow Venice resident Giacomo Gastaldi in 1546, four years after Jacques Cartier (top) made his last voyage to the New World. Though Gastaldi didn’t include on his map the names of places that have become inextricably linked with Cartier, Forlani did, adding Canada, Stadacone (Stadacona, the Iroquoian village located at the site of what is today Quebec) and, in another instance of a Canadian place name appearing on a printed map for the first time, Saguenai (Saguenay).

As Gastaldi did, Forlani shows North America and Asia as one continent, a geographic myth of the time that he never corrected on any of his subsequent world maps but didn’t repeat on his map of North America published in 1566, which was the first to show the two continents separated by a body of water called the Strait of Anian.

Forlani also built upon Gastaldi’s illustrations of sea monsters, dotting this map with all manner of fantastical creatures (none of which, perhaps sadly, seemed to ply Canadian waters). Doing so wasn’t uncommon, but with his maps being distributed across Europe, Forlani’s illustrations soon became well known and his style was mimicked on maps for centuries afterward.

Forlani stopped making maps in the early 1570s (he may have died in a plague epidemic that swept through Venice in 1573), and by the 1580s Venice’s reputation as a map-making centre par excellence had diminished — but not before Forlani had left his mark and, for Canada, a name.

*With files from Emily MacDonald, archivist, Library and Archives Canada