Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

For more than three decades, biologist Dave Mossop has tracked the fortunes of boreal birds, gathering information essential for understanding and protecting the northern environment. Along the way, he uncovered a mystery that has yet to be solved — one with links far beyond the North.

Mossop, an emeritus professor at Yukon College, studies boreal owls, bufflehead ducks and other large birds that raise their young in holes in the spindly trunks of boreal forest trees. He attracts the birds with a spacious alternative to their usual cramped quarters: 150 nest-boxes, spread over a wide area.

Right from the start the boxes were a hit, and not only with the owls and ducks.

“We’d find families of kestrels, which are small falcons, in about half our boxes,” says Mossop. “It was a very common bird here and it wasn’t the focus of the study. But in 1997 that suddenly changed: the numbers of kestrels began to crash, and by 2007 we didn’t see any.”

The Yukon’s active community of birdwatchers echoed his observations; no one had seen a single kestrel.

Mossop learned from southern colleagues that kestrels were declining across North America, although not as dramatically as in the Yukon. “That isn’t surprising,” he says. “We’re on the northern edge of the kestrel’s range.”

Why have kestrel numbers plummeted in the Yukon? Climate change could be part of the cause — the Yukon has seen some major temperature shifts — but it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly how. The answer may also lie along the little falcon’s migration route.

Mossop has banded many kestrels, hoping to find out where they go in winter, but no one has ever reported seeing one of his banded birds. Improvements in tracking technology are coming, but because radio transmitters (the current best option) are too heavy for kestrels, the migration route remains unknown.

“We suspect they’re flying down the Pacific coast and into California, where there’s been a long drought,” says Mossop. “Birds of prey don’t drink — they need to be making kills. There’s evidence that larger birds of prey can’t make it through that region because there’s nothing to eat. It would be even harder for a kestrel.”

Agricultural chemicals could also be a factor, Mossop adds. “We know there’s a new rodenticide being used in the United States, and kestrels eat small rodents. They also eat small birds and large insects, which exposes them to other pesticides.”

Mossop and his student assistants found a few kestrels in 2008, and in subsequent years the numbers began rising slightly. “On average we now find one box in 10 being used by kestrels, but that’s far below the former number,” he says.

This spring, the group will again hike into the boreal forest to check the nest-boxes for kestrels and other birds. Mossop’s project bears witness to the importance of long-term monitoring for spotting changes in sensitive northern environments — changes that may have implications for other areas of the planet.

“In the North,” he explains, “we’re seeing anomalies far more often than anywhere else, and we’re ringing the alarm bells.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

Science & Tech

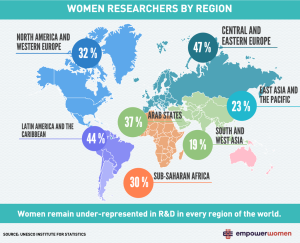

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Environment

Yukon-based ecologists uncover four main patterns influencing changes in Yukon and address how outcomes can be improved

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)