Kids

Giant floor maps put students on the map

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

- 1487 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Mapping

The 60th anniversary of the establishment of Baffin Island’s Dewey Soper Migratory Bird Sanctuary came and went this past June with little fanfare. That it did is not unusual; beyond globally known Canadian icons such as Banff National Park, there probably aren’t many federally protected places whose milestone birthdays would capture the public’s attention.

Maybe that’s because their origin story isn’t altogether as compelling as Banff’s is. Or maybe it’s because their origin story simply isn’t known at all, or at least not known very well. It’s fair to say this is the case with the Dewey Soper Migratory Bird Sanctuary, the background story of which Canadian Geographic tells in its September/October 2017 issue (on newsstands soon).

The story recounts J. Dewey Soper’s search for the breeding grounds of the blue goose (a colour variant of the lesser snow goose), a six-year, 50,000-kilometre odyssey that ended in 1929 when the Canadian naturalist finally pinpointed a site – the location of which had long confounded ornithologists across North America. He did so with guts, determination and, arguably, an obsession that could have seen him meet his end on Baffin Island’s rugged landscape.

But he also did it with the help of local Inuit. Some of these people acted as guides, shepherding Soper across what was then still poorly mapped territory. Others supplied him with information about where and when they’d seen the blue goose. And one, a man named Saila, gave Soper what may have been the most valuable piece of information he’d collected about the blue goose since beginning his search in 1923 — a map.

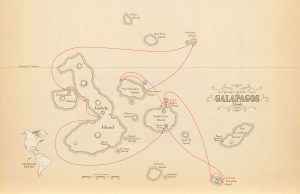

In the fall of 1928, Saila drew Soper the map of west-central Baffin Island that appears below, indicating the location (shown in red) of the blue goose breeding grounds, around Bowman Bay. “This remarkable document…” wrote Constance Martin in Echoing Silence: Essays on Arctic Narrative, “… was an example of the native people’s deep knowledge of the land. Done without surveying skills or measurement, it nonetheless recorded every bay and inlet of the intricate multi-islanded west coast.”

In the summer of 1929, Soper, using Saila’s map, finally located the breeding grounds. A degree of fame followed (accounts of Soper’s success appeared in newspapers and Ripley’s Believe It or Not!) and Soper was immortalized when the federal government established the sanctuary in 1957.

Less well known to the public, however, were the contributions of Saila and the other Inuit who helped Soper, a debt Soper acknowledged when he inked these words on Saila’s map: “This map was drawn by the Eskimo ‘Saila’ in the fall of 1928, as the breeding grounds of the blue goose were discovered by J. Dewey Soper in June, 1929, with the help of Cape Dorset, B.I. [Baffin Island] Eskimos.”

*With files from Joanne Pearce and Erika Reinhardt, archivist, Library and Archives Canada

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

People & Culture

For generations, hunting, and the deep connection to the land it creates, has been a mainstay of Inuit culture. As the coastline changes rapidly—reshaping the marine landscape and jeopardizing the hunt—Inuit youth are charting ways to preserve the hunt, and their identity.

Mapping

If you’ve ever had to help make a map, it gives you a whole new appreciation for the art form. As editor of Canadian Geographic, I’ve found myself more…

Mapping

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.