Scouted, shot, then sold: almost all captive-bred lions in South Africa face a similar fate. Born to entertain tourists, the lions are eventually killed in canned hunts or skinned for their bones.

The realities of South Africa’s captive-bred lion industry were recently exposed thanks to a year-long investigation led by Michael Ashcroft, a British peer and Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. In 2019, he began a covert operation to uncover the extreme cruelty to lions that for decades has gone virtually unnoticed by the public.

The operation involved former British Army and security services personnel, with the team recruiting an undercover agent to infiltrate the lion bone trade. Among other stomach-churning evidence, the agent captured video footage of lions, many suffering from skin diseases, held in cramped and dirty pens at a tourist farm. When the undercover team handed a dossier of the cruelty to South African police, it was rejected and they were threatened with jail time unless they left the country.

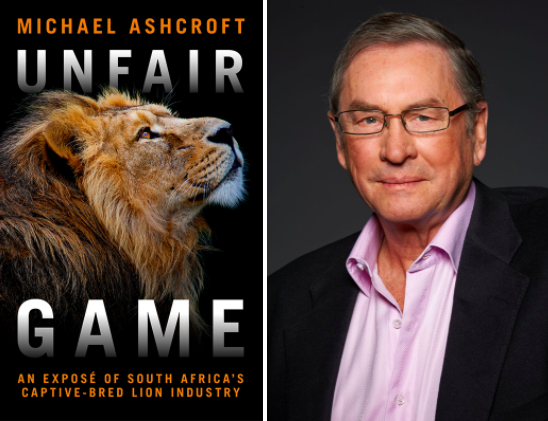

The investigation is detailed in Lord Aschroft’s new book Unfair Game: An Exposé of South Africa’s Captive-Bred Lion Industry. In it, he reveals how lions are drugged, mistreated and hunted for sport on an alarming scale. There are estimated to be about 3,000 wild lions remaining in South Africa; by contrast, lion farms hold about 12,000 of the animals, which are classified as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Canadian Geographic spoke to Ashcroft about this exposé and the message he wants to share with the world.

On what spurred him to write his exposé

When I first heard about the industry, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing—I felt like it couldn’t be true or they were unsubstantiated rumours. I needed to see it for myself. In my first investigation, I personally chartered a helicopter, placed a camera at the front, and flew over six farms to see the pens and slaughterhouses. That was the first time I saw the vast numbers of small pens full of lions, tigers and ligers in poor conditions. Their caretakers clearly had no interest in animal welfare.

On the investigation that followed and his emotional response

The whole experience was harrowing. Having to look at the undercover film of people being deliberately cruel to the animals was deeply disturbing. In the investigation, I hired someone from special forces to buy a lion off the Internet for $25,000, then go through the whole experience of going out on the hunt — to the point where he would have had to shoot the lion, but would make an excuse not to do so.

The footage was highly emotional. I just couldn’t believe that a small group of people in South Africa would be so cruel to these lions. I decided I would do a further undercover operation to see if I could eventually produce a book and hopefully get to a position where this industry could be banned.

On the challenges of mounting the undercover operation

I couldn’t have done this operation in a normal sense of investigative journalism. The people involved in the captive-bred lion industry are aggressive, paranoid and hostile to outsiders. After all, they know they are criminals. Their farms are completely fenced off, patrolled by staff to ensure there is no intrusion and are located many kilometres from the main roads—you simply cannot call them up and ask for an interview. So that’s why I put together a team of special forces who played various roles to get right under the skin of this industry.

On tourists unwittingly being used to support the abuse of lions

At these breeding farms, cubs are taken away from their mothers at birth. Very young cubs are meant to sleep for 18 hours a day, but instead they are played with and handled by tourists and are then kept in poor conditions when they are out of sight. Their destiny is to be badly treated until they are old enough to be shot in a canned lion hunt or killed for their bones. This is ethically, totally unacceptable and of course we should care. I even feel emotional discussing it. We have a responsibility as the dominant animal species on this planet to look after all our fellow animals.

Watch: The shocking truth about lion farming in South Africa (warning: contains graphic images of animal cruelty)