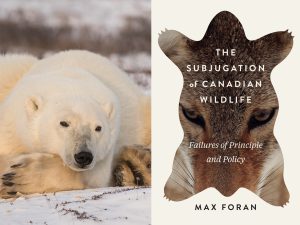

“If you shoot a polar bear with a dart and the ice is thin and broken up, it could get into the water and drown. It’s not a safe environment for researchers either.”

Steven Amstrup is Chief Scientist at Polar Bears International, an organization dedicated to polar bear conservation and public education. More than 40 years of experience has given him a unique understanding of the challenges, costs and dangers associated with polar bear research.

There are 19 distinct polar bear subpopulations, 14 of which are in Canada or based on land Canada shares at least a partial claim to. The remaining five are spread between areas claimed or partially claimed by Russia, U.S.A., Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Since the start of satellite records in 1979, the number of days per year that sea ice is present has declined in every single region.

Take the Barents Sea area, which encompasses Russian and Norwegian territories. Data collected by the Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) for their 2021 polar bear status report shows that since 1979, there has been a 156-day reduction in days that sea ice is present. This means 156 fewer days per year for polar bears to hunt seals — their preferred prey — in ideal conditions. The story is consistent across each subpopulation. Where once there was multi-year sea ice, there is seasonal ice; and where once there was seasonal ice, there is open ocean. In 2018, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration concluded that multi-year sea ice had declined by 95 per cent since 1985.

With sea ice disappearing at the rate it is, one would expect polar bears to be doing the same. Yet the reality isn’t so simple.

The PBSG 2021 polar bear status report showed that while three of the 19 subpopulations have likely decreased over the last generation, four are stable (including the Barents Sea subpopulation) and two have actually increased. The remaining 10 subpopulations lack reliable data to such an extent that trends can’t be determined. Why is our picture of the status of polar bears — an iconic symbol of the fight against climate change — still so murky?

“Polar bears live so far away from people that logistical arrangements can be very difficult and very expensive,” says Amstrup. “So it’s always been a challenge to gather data. In fact, costs are going up dramatically.”

Amstrup says that while we have a good understanding of what polar bears require to live and their genetic status, their way of life makes it difficult to track population trends.

While bears do spend time on land — particularly females with young — much of their lives are spent at sea, says Amstrup. Moreover, satellite tracking shows the bears have the potential to cover a massive range. One satellite-tracked female trekked 4,796 kilometres from Alaska to Greenland to Ellesmere Island and back to Greenland. To even use this tracking method requires researchers to go out onto the ice, far from human settlements, and capture, tag, collar and release the bears.

“That really is expensive work,” says Amstrup.