Places

National parks beginning to reopen across the country

Not all, but many of Canada's national parks will reopen to some extent on June 1

- 438 words

- 2 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

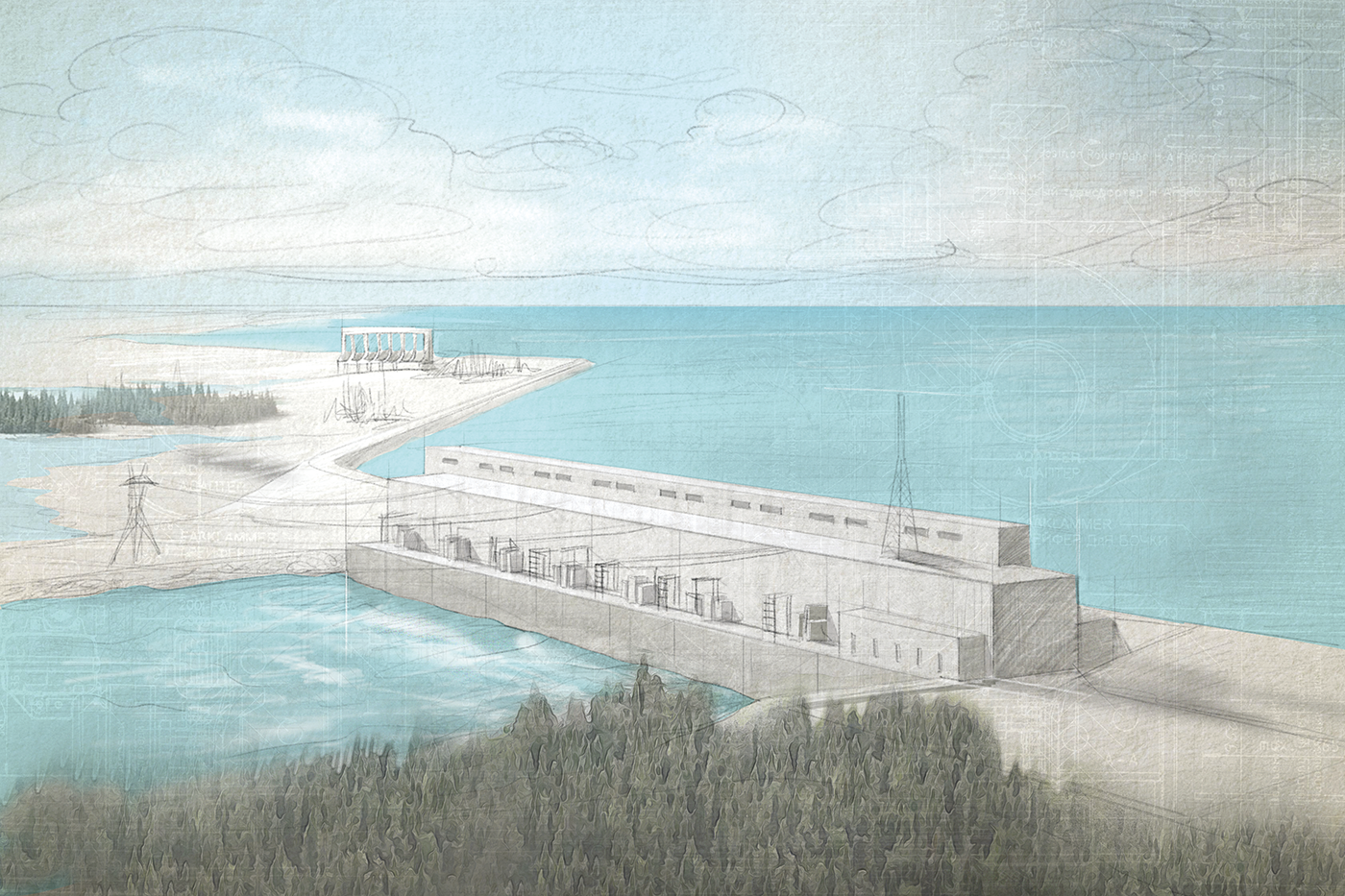

IN THE LATE 2000s, Manitoba Hydro began working on a longterm scheme to add almost a thousand megawatts of new generation capacity with a pair of hydro dam projects in the province’s north. While these facilities were meant to serve a growing domestic population, Manitoba Hydro officials knew they’d have a surplus and looked to markets outside the province.

Around the same time, Minnesota Power executives were looking to reduce the utility’s reliance on coal, which produced 90 per cent of its electricity. The two utilities formed a plan that involved the construction of a 565-kilometre transmission corridor from Winnipeg to Duluth, Minn., with the ability to send 883 megawatts south or bring back 692 megawatts. The estimated cost: $1 billion.

Such projects are both rare and difficult to bring to fruition because of regulatory obstacles, says David Cormie, Manitoba Hydro’s division manager for power sales and operation. “It was the alignment of the stars — a concern for the environment and a political and regulatory view in Minnesota that leads the nation in terms of reducing emissions.”

Ever since utilities in Ontario and New York State strung transmission wires across the Niagara gorge more than a century ago, Canadian energy has tended to flow across the national border instead of provincial ones. While some hydro power generated in British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador flows to neighbouring provinces, the surplus Canadian electricity flows to the United States. After the completion of the line to Minnesota in 2020, more than half of all Manitoba’s electricity exports will go south.

With rapid improvements in the costefficiency of wind and solar, Minnesota has invested heavily in these intermittent renewable technologies, which work best when paired with large hydro stations where reservoir levels can be raised or released when wind and solar farms aren’t as productive. “We act like a rechargeable battery for the U.S. grid,” says Cormie.

The cross-border trade in hydro power is now growing across provinces too. Last September, for instance, the Ontario and Quebec governments signed a far-ranging memorandum of understanding that included a pledge to boost interprovincial trade in electricity.

In Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador, meanwhile, energy officials are focused on both Atlantic Canada and the northeast United States, where provincial and state governments are looking for alternatives to coal. Large hydro projects on Quebec’s north shore and the Churchill River will supply power to Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and, eventually, New England. The hydro produced by La Romaine, for example, a 1,550-megawatt complex of four hydro dams under construction on Quebec’s north shore, upriver from Havre St. Pierre, could allow the U.S. to “get off coal,” says Céline Belzile, Hydro-Québec’s chief environmental officer.

Beyond the EPA’s new clean energy mandate, the Paris accord likely means U.S. utilities will be looking for more low-carbon energy sources, while consumer use of electric heating and electric vehicles is expected to drive consumer demand. “If you look at the combined demand for clean energy over the region, it’s substantial,” says Ed Martin, who served from August 2005 to April 2016 as the president and CEO of Nalcor Energy, the private utility that manages hydro power in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Getting all that energy to market in an economical and politically acceptable way, however, poses a significant hurdle, especially when compared to more straightforward export-oriented projects, such as the Manitoba-Minnesota transmission corridor.

For educator resources, including six lesson plans relating to hydro power in Canada and this story, visit hydro.canadiangeographic.ca.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the June 2016 Issue

Places

Not all, but many of Canada's national parks will reopen to some extent on June 1

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it

Science & Tech

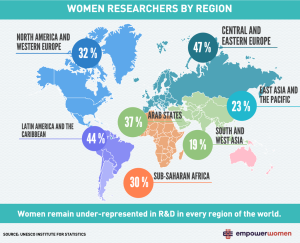

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

History

Sites across Canada honouring the war