Science & Tech

UN declares International Day of Women in Science

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

- 472 words

- 2 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Researchers have taken DNA fragments hidden in a tooth dug up from a 1,500-year-old double burial to map out the gene sequence of two of the worst plagues in European history.

Hendrik Poinar, an anthropologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, has put together pathogen DNA to link the Bubonic and Justinian plagues in a diseased family tree based on a bacteria called Yersinia pestis.

The Justinian plague ravaged much of the world in the sixth century, killing 30 to 50 million people. The burial, dug up in Bavaria, showed artifacts and signs consistent with the plague, and the archaeologists contacted Poinar. After enriching the genome, Poinar found pathogen genomes that were similar to those of the Bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, which killed 30 to 60 per cent of Europe in the 14th century. The two diseases are estimated to have killed nearly 100 million people in total.

This new information could help predict future strains of the plague.

“We’re into the basic understanding of the tempo and mode of the Justinian strain,” Poinar says. “It’s kind of a boom-bust situation. It erupted, killed a lot of people and then went extinct.”

While the Black Death continues to pop up in isolated incidences across the world, the Justinian plague never appeared again and Poinar is interested in what stopped it. He thinks one of the reasons the plague may have disappeared in Europe was due to changing climates that affected the ecology of the species of rats that typically carry it and transmit it to humans through fleas. He says that broader knowledge of the kind of weather suitable to these rats could help pinpoint potential plague outbreaks in the future.

“It would be good to know that rodents in certain areas could create pandemic plague,” he says, adding that the information could help alert local authorities of the potential danger.

Poinar says the chances of another pandemic like those that levelled Europe in the past is unlikely, noting improved sanitation over the years. But the plague usually lies dormant for centuries, and still occasionally appears in parts of Africa, China and the Middle East.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

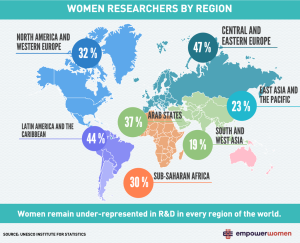

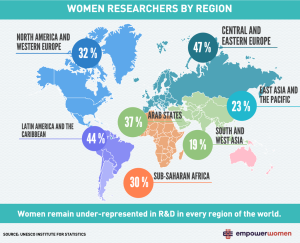

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)

Environment

Carbon capture is big business, but its challenges fly in the face of the need to lower emissions. Can we square the circle on this technological Wild West?

Science & Tech

Dr. Molly Shoichet discusses her new role and how she plans to restore the public’s trust in government science