Exploration

Tracking a 37-day expedition in the Monashee Mountains

Reflecting on an epic 600-kilometre ski traverse across the southeastern B.C. range and charting human and wildlife activity along the way

- 1591 words

- 7 minutes

Mapping

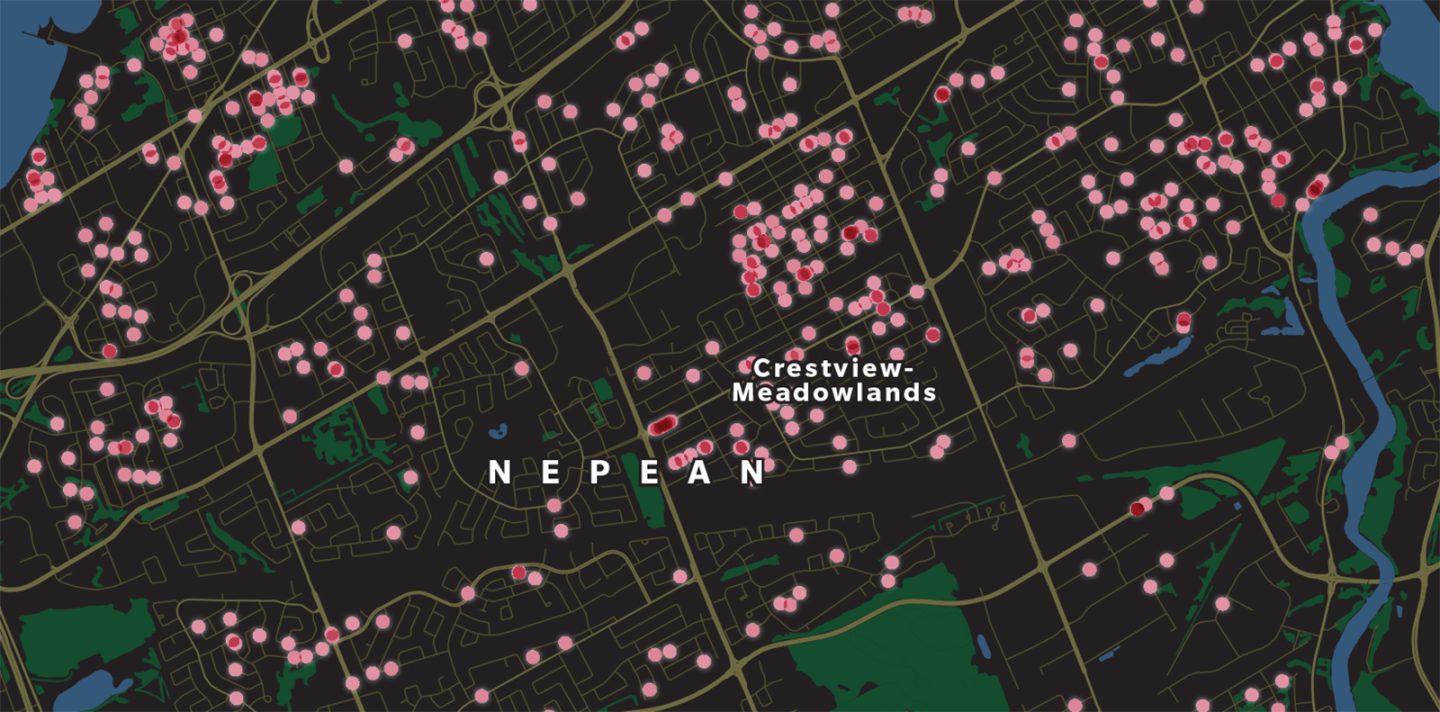

It’s a force that transforms neighbourhoods and whole cities, but gentrification has always been notoriously hard to track. That’s especially true in major urban centres, where city councils and planners must consider how the phenomenon can simultaneously reinvigorate older neighbourhoods and displace low-income families and small businesses.

In the past, researchers have looked at census results to track gentrification, but that data is coarse and updated only in census years. They’ve also sent out co-op students to make visual assessments of a handful of streetscapes and compare those assessments over years, but that’s time-consuming and fails to paint the big, coherent pictures cities require.

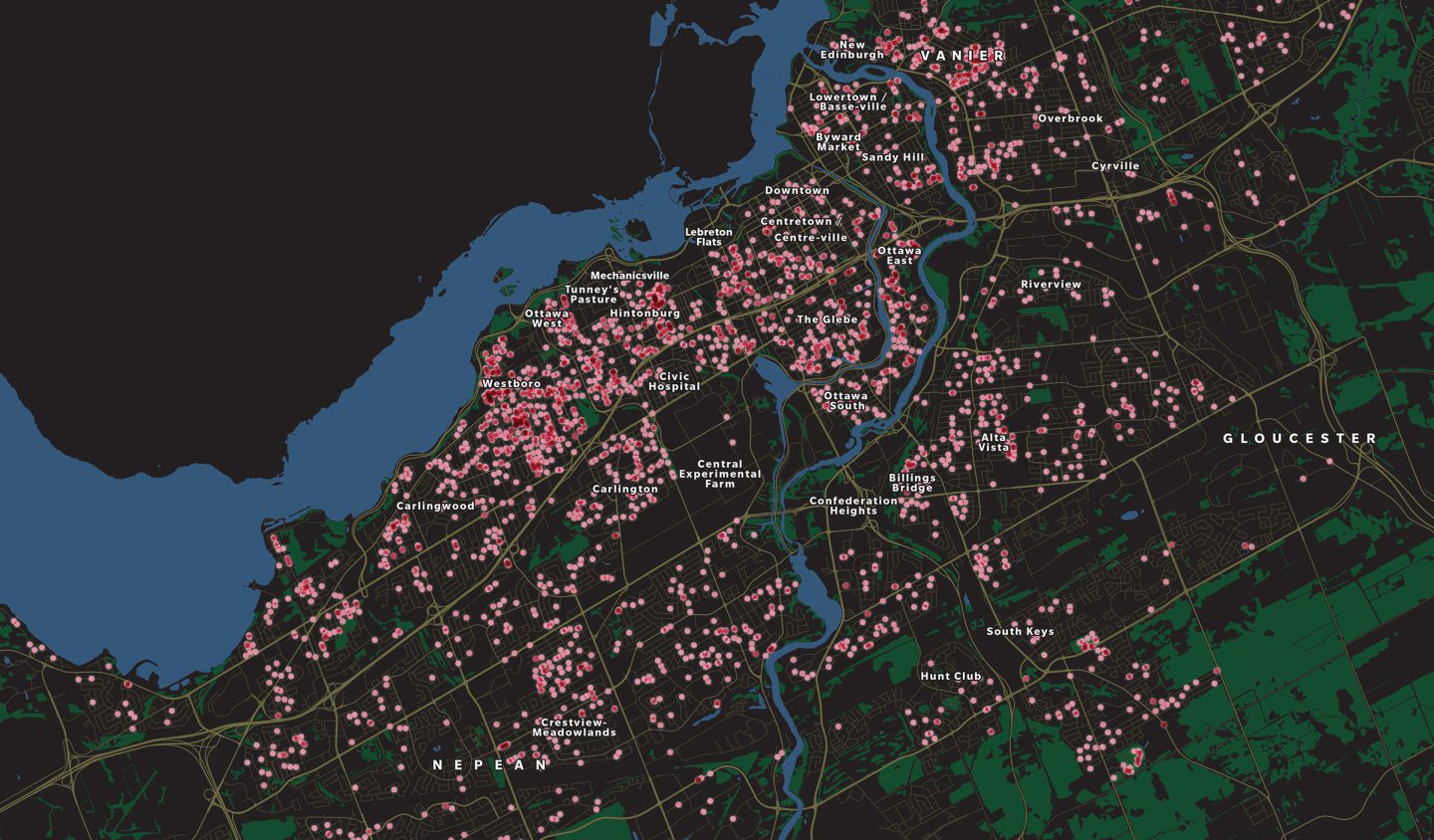

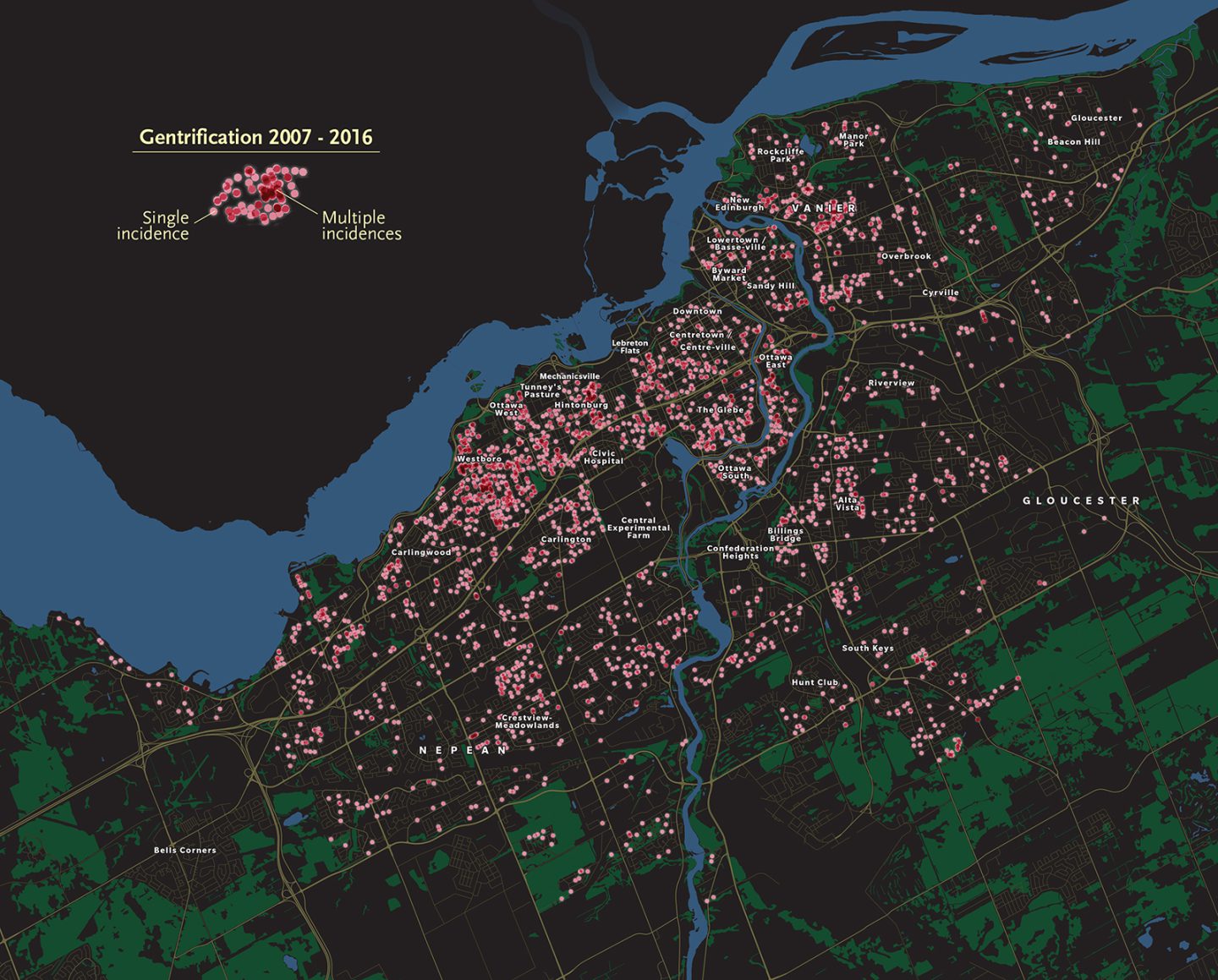

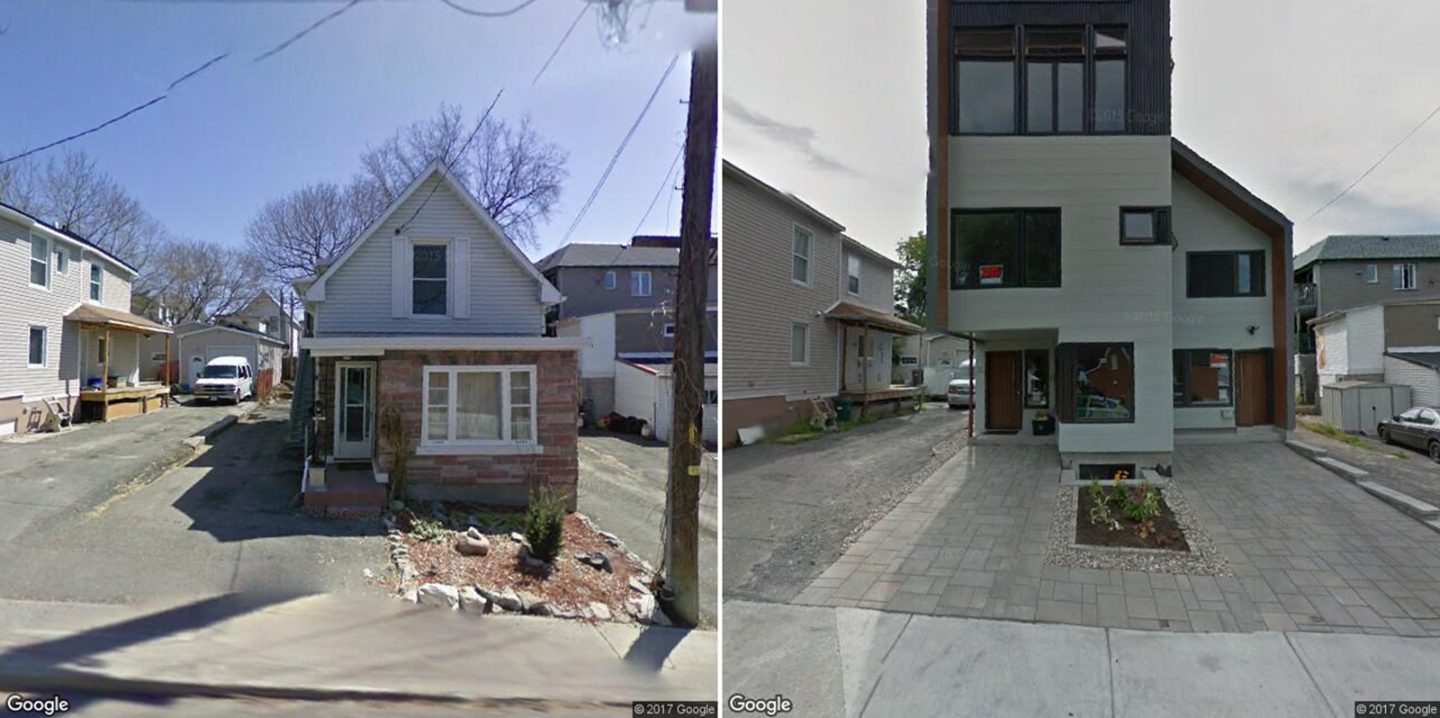

Enter Michael Sawada, a professor of geography, environment and geomatics at the University of Ottawa. In a first-of-its kind study published in 2019, he and students Lazar Ilic and Amaury Zarzelli trained a powerful new “deep-mapping” computer model to recognize visible signs of gentrification as it scanned hundreds of thousands of Google Street View images (from 2007 to 2016*) of more than 157,000 properties across the Ottawa neighbourhoods shown here. With 95 per cent accuracy, the model flagged street-side improvements ranging from fresh paint jobs and window, siding and fence replacements to extensions and entirely new houses. Expensive cars, new kids’ parks and public art installations are also good indicators, “but the home,” says Sawada, “is the atomic unit of gentrification.”

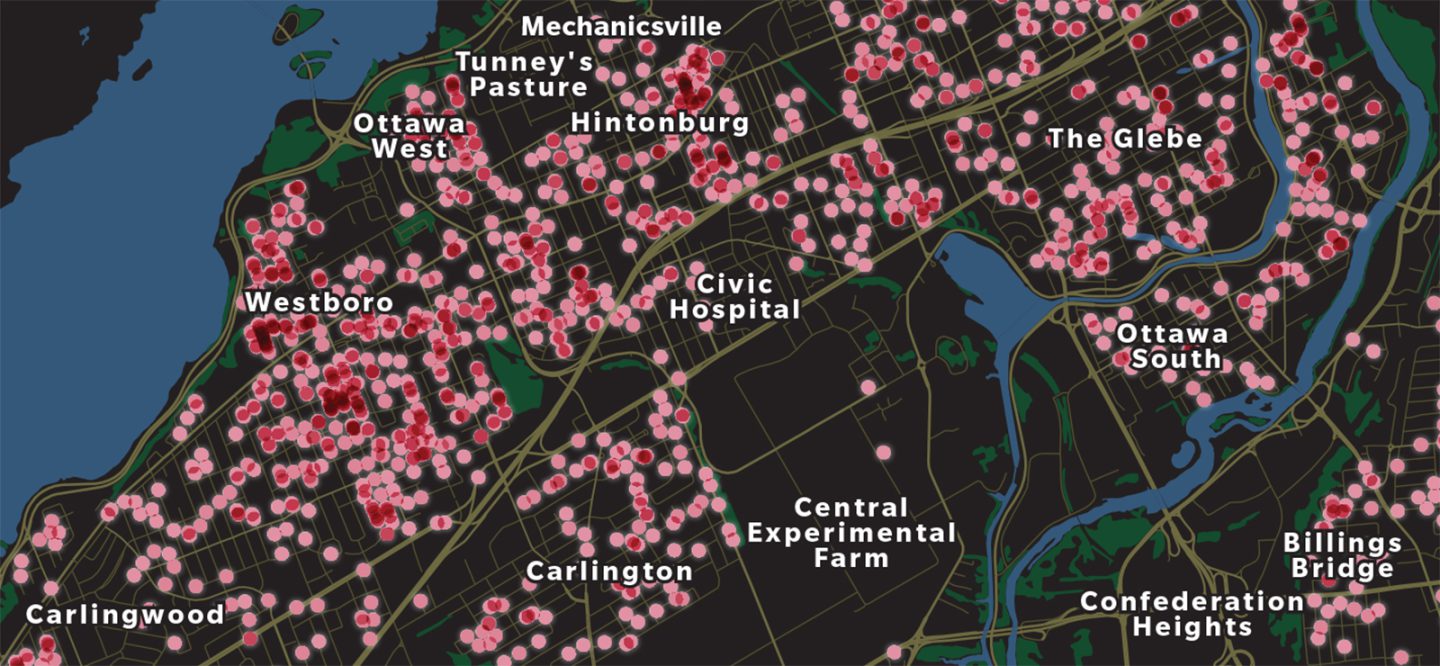

In all, the study confirmed 3,483 instances of gentrification at 2,922 Ottawa properties over the course of the decade. The data, which pinpoints where and how fast gentrification is happening, reveals neighbourhood evolution but also challenges. Hintonburg, Mechanicsville and Westboro, all west of Ottawa’s core, are at least locally famous for their ongoing intense redevelopment and, in some areas, densification, but the researchers also found gentrification in full swing in neighbourhoods such as Crestview-Meadowlands (nine kilometres southwest of downtown Ottawa). There, property values have skyrocketed in the last decade and it’s not unusual to see a $2-million home or two $1-million homes rising where an original single-family bungalow stood. “That means some middle-class people who sell their old homes can’t buy back into their neighbourhood,” says Sawada.

The results of this project could be harnessed for addressing inequality — particularly for providing more affordable housing, says Ilic. “This is a major issue right now because there is simply a lack of it. But this data lets city planning departments look at the hot spots and say ‘Ok, those are areas where there’s a need for funding, or requirements need to be put in place for developers, because people are being pushed out.’ ”

*Google’s terms of service changed in 2018, limiting the number of Street View images freely available to the researchers to 25,000 per month (they were previously able to download and cache 25,000 per day). In order to expand the study to other cities, Sawada’s team is now testing the viability of crowdsourced geotagged images (mainly collected through dashcams) from Mapillary.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

Reflecting on an epic 600-kilometre ski traverse across the southeastern B.C. range and charting human and wildlife activity along the way

People & Culture

In the April issue of Canadian Geographic I wrote about Stratford, Ont.'s three decade struggle to repurpose the giant, neglected railway…

People & Culture

What does it mean for Canada if we continue to pull up train tracks?

People & Culture

From immersive art installations to dining in the sky, Ottawa hopes to reintroduce itself to the world in 2017. Here's a sneak peek of what's in store.