People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

In the April issue of Canadian Geographic I wrote about Stratford, Ont.’s three decade struggle to repurpose the giant, neglected railway repair shop that looms near downtown (see photos here).

Although that story featured much frustration on the part of passionate locals, it also inspired me to look for urban development success stories. I found one in Zibi: a plan to develop 15 hectares of historic land on two islands and along the shorelines of the Ottawa River on the Ontario-Quebec border between Ottawa and Gatineau (read more about the project here).

Jeff Westeinde, CEO and co-founder of Windmill Developments, is the force behind Zibi. What follows is an edited transcript of my chat with him.

Zibi is nothing if not ambitious. The retrofitting of historic buildings, the construction of new ones, a river clean-up, rehabilitation of the Chaudiere Falls — all of it on land in the centre of the nation’s capital, and on land sacred to First Nations. Can you talk about how you got started?

When people ask what is behind our success with this project, I sometimes say, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that all we needed to do was get Canada’s three founding nations to get along. That is really what we’ve been up to here for the past few years.

I think that if I can point to a single thing that we did that was a catalyst to get things moving it was that we worked really hard with a broad community. Most developers will engage with the community they are forced to engage with through a zoning or land use change process. There is a process mandated, public consultations and so on, and you have to go talk to the community associations, whatever. And so they will do that because they have to do that. It’s the bare minimum.

What we did instead was recognize that our two cities — Wrightville and Bytown originally, Gatineau and Ottawa now — started here at the confluence of three rivers, and before that had been used essentially as the truck stop for traders, for commerce with First Nations. It was a also sacred site for our aboriginal people.

We knew that the property, once we purchased it in 2013, was just far too important for us, as a developer, to singlehandedly imagine what the future should look like. So we tossed a very broad net, we were very inclusive, and took the position that we don’t know really what this project should be. And so we said, ‘Let’s start with almost a blank sheet of paper and develop the key principles we want to follow as we develop this site.’

From that, we identified seven development principles and held our first public consultation. Not because we needed to but because it was where and how we wanted to start. And 900 people showed up, which is quite a lot for a first meeting.

We did things some things that might seem counter-intuitive. In this part of the world, the nation’s capital, it is standard to have a consultation one night in English and the next night in French. But we said, ‘No, we’re going to have a single consultation and we’re going to hold it in Gatineau because there is a general rule that the majority — in this case, Ottawa — has less of a problem meeting on the minority’s turf.

If we had a criticism that night it was, ‘Why isn’t there anything for us to see? We expected to see plans.’ We told them that we wanted their thinking about what should be in our plans.

So what came of the meeting?

The result was a very broad-based consensus around how we should measure success, and we were then able to, as we walk through the detailed rezoning process — and there were regulatory reasons why certain things couldn’t happen — we were able to point to two keys areas.

One was that, as a community, we had all agreed we wanted to do something that was world class. We wanted to do something that stands out on the planet. And so we were able to remind the authorities, as we moved along, that world class means doing something different.

Authorities by their nature and their mandate want to make everything the same. If you look at streetscapes, for instance, they want them always to look the same — sometimes for good reason — it’s easier to get the snowplows down there, for instance, or the fire trucks. But after our meeting, our consensus, we were able to remind them that, no, world class means something different and that we as a community agreed that’s what we wanted.

The second thing we were able to do, and we did this several times, is publish report cards grading the principles that were stated at the outset. Often these would deal with regulatory approval authorities. We’d draft a report card and we’d say, ‘Well, so far we have a D, a D, an E, a D an F and an E.’ And if asked why the bad marks, we’d say, ‘Well it’s because of you guys.’ And more than once they’d say, ‘Whoa, whoa, we don’t want that.’

It wasn’t really us as the developer saying we want more density or we want more money or more whatever, it was a reminder that we have a contract with the public to do our best to achieve the principles we set out to achieve. So, really, it gave us a bit of a moral high ground to work through some of the tough issues.

Can you give me an example, something concrete to illustrate what you’re saying?

JW: Sure. One of our guiding principles states that the project needed to be viable. While it’s great to imagine all sorts of things, if it isn’t financially viable, then it doesn’t matter. So we were able to agree on some core development metrics that were necessary. The number of square feet, for instance, we got agreement with all the regulatory and approval authorities on square footage that makes sense.

So then you start talking about the form of the footage. In Ottawa-Gatineau, because you have two municipal governments and a federal government, they oftentimes have competing interests. The federal authority wants to create a great capital and that doesn’t necessarily mean it has to work for the citizens who live there. It oftentimes is more of a showcase for the country. Meanwhile, the municipalities are saying, ‘Wait a minute, we want walkable streets, a certain quality of life for our residents.’ So there can be tension there.

So when we got into designs, well, the two municipalities each have their own design approval review process, and the federal government has one as well. We asked if the three of them would get in the same room at the same time, probably for the first time in the history of the region. And they did. What that meant was that the city of Gatineau was looking at designs for the city of Ottawa, and vice versa, and the NCC (the National Capital Commission, which overseas federal properties in Ottawa-Gatineau) was looking at both, often in places where they otherwise wouldn’t have had jurisdiction.

So, in a way everyone’s jurisdiction got expanded, but we had a common place and common goal to come to.

But what about those report cards … ?

One of the places where we got a low rating was when we started talking about the form of the architecture. One of the principles behind the federal government’s view of the capital is that the most important symbols in the city are national symbols and nothing should detract from those symbols. I’m talking about things like the Parliament Buildings, the Peace Tower. So, that means height restrictions — there can’t be buildings taller than the Peace Tower within a certain radius — but more than that it means flamboyant architecture. And I would agree with that philosophy. We’re talking about the kind of flamboyant architecture that would become Ottawa’s new symbols, buildings that people associate with Ottawa rather than the Parliament Buildings, the Peace Tower or the National Gallery or the Museum of History, important landmarks. So I understand why those rules are in place, but it can lead to tension sometimes. We ended up in a situation where there was a debatable height, and a debatable form in our plans. One of the principles for us in the project is that we absolutely reacquaint people with the waterfront. Ottawa and Gatineau are waterfront cities, but we don’t really have urban access to the water in many places. So we really wanted to be sure we have large public realm of walkable, accessible streets on our ground plane. If you start squeezing height, we told the federal people, then you start to decrease that public realm because we needed a certain amount of square footage in our buildings to make the proposal viable.

Were these kinds of things, the height and the look of buildings, part of the discussion with the public?

No, not exactly. With the community as a whole, we never talked about the fact that we wanted certain types of architecture or that we wanted to protect certain viewscapes. But what we did talk about was great access to the waterfront. That’s what the community asked for, and that was one of the development principles we set when we got going. And everybody signed off of those. So this was a situation, our debate with the federal people, where we could turn back to those development principles and remind everyone that this was what we’d agreed on at the beginning and it was something we intended to stick to. We used to call them our Ten Commandments.

Did you use these principles, and the public’s support for them, to bend governments’ position from time to time?

No, I wouldn’t say bend. I think all of the parties involved … we always found a way to reach consensus. Consensus doesn’t necessarily mean agreement on everything, but there was a broad consensus and really it was just having this clear vision that we could circle back to and say, ‘Are we or are we not on track? And if we’re not, let’s revisit what we’re trying to achieve and look at what obstacles are blocking our way to getting there, and how we can address those things.’

If anything, I’d say the party that bent the most was us. But we were very clear about the must-haves and the nice-to-haves. You know, it had to be viable. It was really about sharing a common vision and reminding everyone there was a consensus on this common vision, and to stay on track. And, importantly, we had to remind everyone that the common vision was very broad based. It was bigger than us, it was bigger than the governments and government agencies. It was a community-wide vision, and that I think held us together to get this done.

These are historic lands, and there are some historic buildings on these lands, buildings that were central to the thriving lumber industry that helped to build the region. How integral to the overall project was the repurposing of those buildings?

JW: Oh, it was critical. If you don’t capture the history all your doing is building a new development without a soul. The history of these lands, that’s the soul of the development. I would suggest some examples of that, Granville Island in Vancouver or Toronto’s Distillery District, those developments are interesting, special, because of the way they have captured history and are being used for modern purposes. That is very much the model that was crucial for us, and that’s exactly what we heard from the community as well.

Will there be direct mentions of that history in your project? A musem, say, some nods to what these lands once meant to the early history of Ottawa and Gatineau and, of course, to First Nations people?

JW: Oh absolutely, and it won’t be a small museum, it will be knit into the fabric of the development everywhere you go. You should have a very strong sense of what was here before. The one development that really stands out for us as an example of this is the Distillery District. You walk into the lobby of a new condo there and you will see a rack of whisky casks. Or, you walk through one of the office buildings and at the corner of a railing on a set of stairs there’s a piece of glass, and you stop and look at it and it lines up with the window and etched on the glass is the scene you would have seen out that window 150 years ago. If you are walking around the site you will see some brown pavers that show the waterline in 1820 … the water is now about a kilometre south of that. So you get this really rich sense of how the place used to look and feel and what happened there.

That for us is a real model. In an ideal world, anywhere you walk on our site there will be evidence of the past, the history that made this place what it once was. At the end of the day these lands are a microcosm of the history of the entire country — it all happened on these lands. To be able to recapture that in an interactive way will be really neat.

Where do things stand now with First Nations? I know there are divisions within the Algonquin communities themselves, and that there has been criticism from some high profile figures, including architect Douglas Cardinal, that Zibi is not appropriate for lands of such cultural importance.

Reconciliation is difficult at the best of times, and a lot of it has to do with the core beliefs of some of the different communities. When you look at First Nations communities across the country, you find a lot of similarities but there are differences, too. There is not a homogenous approach. Some communities, mainly in the west, decided to go down the route where they signed treaties and gave up aboriginal title to much of their historic land but in returns received large swaths of land and economic compensation for what they gave up.

Other communities said they didn’t ever want to give up their title rights and their land remains unceded. So, therefore, they want to be actively involved in any development on any of their lands anywhere. And typically what that leads to is opposition to projects, because the reality is many of these communities are quite small — several hundred people — and if you look at the size of the territory and what it takes to administer that properly, well, it gets overwhelming pretty quickly.

All that to say there are some core principles that separate some of the Algonquin communities that we, as an developer, were simply never going to overcome. But I would say that, by and large, our relations with First Nations people are excellent, and that the opposition we are seeing was expected.

At what point did you involve First Nations in the project?

Right from the start. We identified pretty early on that these lands were, physically, the meeting place of the three founding nations — aboriginal, French and English — and they had historical importance to all three. So, right after we signed a letter of intent to purchase the site, our very first meeting was with the Algonquins.

That was 2013. You moved pretty quickly to get things to this stage so quickly …

We’ve been very fortunate that we captured the imagination of the public. We enjoy broad-based support, and that helps a lot. You know, those lands have been studied to death by a whole variety of governments for a whole variety of proposals over the years. There have been a couple of fairly detailed masterplans of what that land could look like. Gatineau has done quite a few plans of its own. These lands have been on the radar screen for a long time. But industry didn’t fully shut down there until 2006, and it has only been since that time that there’s been a real tangible possibility of something happening on the lands, something like what we’re doing.

That makes it unlike Stratford, from the little I know, where the building has been vacant a long time, and there have been active proposals to do something that have stumbled. We haven’t had that situation. But I can tell you that when we first announced we had a letter of intent to purchase these lands in 2013, it was unanimous among our peers in the development industry that we were out of our minds, that there was no possible way this would ever see the light of day. So, you can see we overcame a lot in a short time. We’re proud of that.

Can you talk a bit about that disbelief, what you were up against?

Oh, the disbelief that we could get something started here was pretty strong, at least among others in the development world. But it was different with the community. The mood at the first meeting was very strong, very supportive. We signed a letter of intent in May 2013 and the first large public meeting was in December 2013. In those six months we had started to receive messages of support from the NCC, from the ville de Gatineau, from the city of Ottawa and from the Algonquin community. I think people in the community, residents, started to think, ‘Well, if all of these people are engaged with the developer and supportive of development, while it’s early days, then maybe this thing could actually work.’ So by December I would say there was keen interest by the public in what this was all about, very keen interest to see something innovative get done.

You know, it may sound counter-intuitive, but in our case, the fact we were a private developer played a very strong role for us. It helped us. In Ottawa, when the federal government develops, there is very little chance for the citizens of the region to have input. Since we were a private developer, and one already known for being fairly inclusive, I think there was a feeling that the community — and by that I mean all of the communities, the federal government included — could have a strong say it what happened. I think that was seen as a positive.

So how much of the final product, then, is an amalgam of the community’s ideas?

What we view our job as, quite simply, is to take the views of everybody else and turn them into a viable plan. Here’s an example. One of the things that came out loud and clear at public meetings and during consultations was that people wanted a walkable community. So, we looked at the metrics and targeted a walk score of 85. What that means is that very rarely would you need a vehicle if you lived or worked there to do anything. You have the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker all in the neighbourhood. Then you have to ask, what do those people need — what does a coffeeshop need to locate here, same with a dry cleaner and so on? So you start working backwards from that to determine what you need to put into the neighbourhood to make all of this come together and achieve your walk score.

What you more commonly see in projects like this is the developer saying, ‘How much density can we get on this property without getting ourselves into trouble?’ That’s a very difficult approach to take if you want to engage a community. Whereas, if you specify what kind of community you want, you can then think rationally about what you want to put there, what’s needed to make it that kind of community.

Do you have a sense of who will live there? How can you sure it will be a mixed community rather than, say, something like the condo jungle in Toronto where everyone is a professional under 35 without children? Or a community of only high-income people? Or doesn’t it matter?

Our overarching vision is that we want to be the world’s most environmentally and socially sustainable community. Environmental sustainability is well understood by the public, I am not sure about social sustainability. What it means is you need to have a mix. If all you have is the middle class, or upper class or social housing, that is not a community. A community includes all of those people, and more. We have been working hard on ways to make sure we end up with a mix. We have been talking to some of the social housing people, and we’re telling them we do not want a building just for social housing — we want social housing units in every residential building we build. The authorities are not used to administering units that are spread out like this, they are used to looking after a specific building. So, we have some issues we are working through. We are also looking at housing for First Nations, for artists, and we’ll probably have some of the nicest homes in the region on the site, and everything in between. If I can be allowed to boast a bit, Windmill has built some of the most environmentally sustainable buildings on the planet. However, if someone wants to drive a Hummer into one of our parking areas, well, we have to ask ourselves whether we have really moved the needle that far.

So the next target for us is really this social sustainability idea. The way we’re approaching it is the same way we did it with our environmentally sustainable buildings. We want to make it so easy for people to reduce their footprint that they don’t even know that they have. They walk into their home, they still have granite countertops, their heating and cooling works the same as everywhere else — however, their footprint is substantially less because of the building they live in.

When it comes to social sustainability, we think we can make it so easy to walk, bike, car share, create a caring community where people in social housing live next to professionals, where people can run up against one another and become true caring neighbours, versus saying we have to go down to the food kitchen to help that segment of the community. Ideally, it would reduce stigmatization.

Looking back, are there things you would have done differently?

On the First Nations file, we engaged largely with chief and council — well, really, with just the chiefs in the very start — whereas in the non-native community we engaged with mayors and council but also cast a wider net into the general community. We didn’t do that with First Nations, and we should have. We’ve now done that. If we were to do it again, we would start much earlier casting a wider net into those communities rather than relying on chief and council.

What about the name? There was a bit of a fuss about using an Algonquin word for the project.

We had actually sought endorsement for the name, Zibi, from First Nations groups. We sent four letters to four communities, and we got endorsements from two and didn’t hear from the other two. And it was the two who didn’t respond who were initially critical of the name. I called them both after and said, ‘Remember that letter I sent that you said you read, well it was in there. They were, like, Oh, sorry … ‘

Look, you are always going to have controversy if you take 37 acres in the heart of the downtown of any city and re-imagine the future. There is always going to be someone who is unhappy, and we have tried to listen to the community about these things as much as possible. Generally, we are pretty satisfied with where we are to date, and the process we followed. I think you’d hear the same if you asked the community and the mayors and councils and the NCC. There are lots of irritants in a project this size, of course, but overall we’re very satisfied with how well it has gone, with our working relationships and the trust we have built. People have stayed focused on the larger common vision, the bigger picture.

Is this project 100-per-cent Windmill, or is there public sector involvement financially?

This is a private development. Of the 37 acres in the site there is a little under two acres of land that fall under perpetual leases from the federal government. They came about from the day when the industrialists filled in a little of the river and created more land. So it’s quirky that way. The federal government is involved in that parcel of land from a landowners’ point of view and we’re working on a strategy to clean up all that land with them. But overall it is a private sector project being done by a private developer. We’ve brought in Dream Unlimited, one of the developers of the Distillery District, as a partner as well.

Were there heritage restrictions, limitations on what you can do with the buildings on the land? Can you talk a bit about that?

Yes, there are some buildings on the Quebec side that are protected under heritage designations but other than that none of the buildings currently have any heritage status. Having said that, I think Windmill has built up a high level of trust and credibility with the heritage groups because of the other projects we have done. I think I can confidently say that I don’t think anyone is terribly concerned that significant heritage structures would be erased or radically changed without a broad-based consultation explaining why we’re doing it. With all of these projects you have to have a high level of trust. If you try to just use the enforcing rules to achieve what you are looking for — those are not insignificant, of course, and there are always rules that are not perfect for your situation and have to be talked through — but you are always better off agreeing on the outcomes you are trying to achieve at the outset. And then, based on those outcomes, you can start to come to decisions as you go along.

I realize the two situations are very different, the history and complexities and communities, but do you have any advice for the people and politicians in Stratford as they try to figure out what to do with their massive old railway repair shops?

I don’t know the site and history in Stratford that well, but the one thing I would absolutely say is that market viability is going to be a very important component of the project if it involves a private sector partner. It simply has to make sense financially. Otherwise, why make it happen? It is worth noting that, by and large, communities are anti-change, and the community needs to embrace measures that make a project viable. And I think that would probably more true for communities the size of Stratford. When I say embrace, I mean it really takes the community to take a pragmatic approach to the facts, to embrace the ingredients that are important to the developer and to be clear about what things the community and the developer will allow to happen to ensure the project can move forward. It’s also worth remembering that developers have lots of choices when it comes to these kinds of projects, all through southwestern Ontario and into the states. So, the developer has to feel like the community wants his project, wants to buy into the vision — a shared vision, of course — but one that is viable and practical.

Turning back to our project for a moment, there is a strong contingent in town that would have loved to see a park on the island. From experience, you know there will be suggestions from the public or government that you just can’t do to make the project viable. So after our consultations, we issued a report in which we answered every suggestion we heard with a classification as being something we will do, something we’ll consider doing and something we can’t do. So, say, on the park idea, we said that as a private sector developer developing private lands that are contaminated in many places and have a significant cost to clean up, we simply can’t do the entire island as a park. It’s just impossible. Those kind of things require leadership in the community to stand up and say, yes, we understand why it’s not reasonable.

Again, I don’t know the history of the Stratford site, but controversy and uncertainty tends to drive developers elsewhere. They look at a thing like that and say, ‘Why would I go there when I have so many other choices without all these difficulties and where I stand a better chance of having our ideas met with some enthusiasm.’

I’m sure you’ve spent some time looking at other projects with historic significance in Canada. What do you like out there, what’s really hit the mark in your view?

Well, for starters I really think the Lachine Canal District in Montreal has been a great success. Also Granville Island, while it is older, to my mind has been a fantastic thing. And, of course, the Distillery District is just tremendous. And if you look at each of those projects they have very different components. Granville has no residential, the Distillery District has a lot, the Lachine Canal has some. Each is successful because they looked at the mix of what was around them and did what they needed to do to augment and enhance that to create a successful neighbourhood. The ingredients are never the same, so you have to know what to do to build on what’s there to incorporate it, be inspired by it and to enhance it.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

Across Canada, there are old buildings finding new life through modern transformations. But such metamorphoses are complicated. Indeed, for the past three decades, Stratford,…

People & Culture

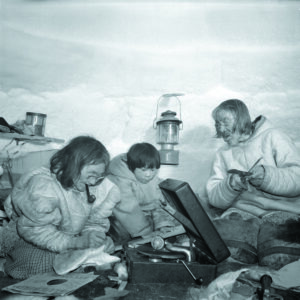

Launched in 2002, Project Naming invites Canadians to engage in identifying Indigenous people from Library and Archives Canada to help tell the story behind every photograph

People & Culture

The death of an unhoused Innu man inspired an innovative and compassionate street outreach during the nightly curfew in 2021