People & Culture

On thin ice: Who “owns” the Arctic?

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

- 4353 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Although we crossed paths a couple of times at the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, I really met Bill at Purple Hill, his iconic underground home on the rolling Oak Ridges Moraine northwest of Toronto. He and his wife Paula were hosting a party to celebrate the resolution of legal difficulties that had arisen from the grounding of a ship called the Sea Adventurer on a massive rocky ridge in the middle of the Coronation Gulf in the Canadian Arctic. Everyone at the party had some kind of connection to Adventure Canada, the company that had chartered the ship and hired people like Bill to animate it; indeed, many in attendance had been rescued from the stranded ship.

It was the day after Halloween. In addition to the menagerie of metal sculptures scattered about the property, the Lishmans’ long country laneway was dotted on one side that day with a line of fat pumpkins. With all that was going on in and around the house, it came almost as an imposition when, a couple of hours into the festivities, Bill, looking like the benevolent madman that he was — hair askew, spring in his step, twinkle in his eye — came up from the airstrip and herded everyone outside. He then arranged us, like a director with parade-watching film extras, into a line along the lane, opposite the pumpkins. “Not too close,” he said, as if the pumpkins were somehow radioactive.

By now, a new item had appeared at the end of the line of pumpkins: a handsome and realistic sculpture of a rock the size of a good-sized goat, with a familiar-looking expedition vessel perched on top of it. The model might have been a metre or so long and, like the rock, was beautifully hand-painted. As the guests took in this scene, the sculptor himself was scurrying about, connecting wires to each of the elements on the laneway.

He then appeared with what looked like a WWII-era T-detonator, very similar to the ones Wile E. Coyote used to try to blow up the Roadrunner on Saturday morning cartoons. This he set down with great ceremony, like P.T. Barnum in the centre ring, and casually asked for a volunteer from the audience.

“Press it,” he said with the enthusiasm of a child to the unsuspecting person who had stepped up. Nothing happened. The crowd booed eagerly. Undaunted, Bill checked the pumpkins, fiddled with the wires, pulled the T-handle back to its neutral position. “Press it again.”

With that, the first pumpkin in the laneway lineup exploded. Then another, and another, and so on down the line. Pumpkin pulp flew everywhere. The guests were incredulous, perhaps even a little stunned.

After about a dozen splendid orange explosions — there wasn’t a person in the crowd that day who didn’t go home with pumpkin on them somewhere — the detonator was attached to the sculpture at the end of the laneway. I forget now who was invited to press the “T”; it may have been Bill’s friend Matthew Swan, the founder of Adventure Canada.

“Fire in the hole,” someone yelled as the plunger was pushed home. The “rock” (which was made of glued sheets of carved and painted pink Styrofoam insulation) splintered into ten thousand tiny pieces that rained down on Purple Hill like volcanic ash, leaving the ship proudly standing on a metal rod, as if finally freed from its perch. Vintage Lishman delight.

Bill Lishman’s truly remarkable life has been well documented since his passing, and his obituaries have revealed new details. For example, he’d mentioned that he left high school early and that he’d completed the credits for the Ontario matriculation certificate by correspondence. (Lishman was dyslexic, and schools in the 1950s were not equipped to do much for an exceptional learner other than demonstrate repeatedly that he was not like the other kids in the class.) But what he’d neglected to let on was that his high school exit was actually precipitated by some kind of incident involving dynamite. Apparently, what we’d witnessed on the lane at Purple Hill that November night hinted at something of a lifelong fascination with blowing things up.

I asked him, picking pumpkin pulp off my face, if he’d had any kind of special effects training or demolition experience. “Hell no,” was the emphatic reply. “I just got some party balloons and filled half of them with acetylene and half with oxygen — you know, welding gases. You stuff them in the pumpkin, add a blasting cap, connect an electric current and blam, you’re all set.”

“How did you know how much gas to put in each pumpkin?” I asked.

“I just took a guess,” he said. “It worked, so I guess the guess wasn’t too far off the mark.”

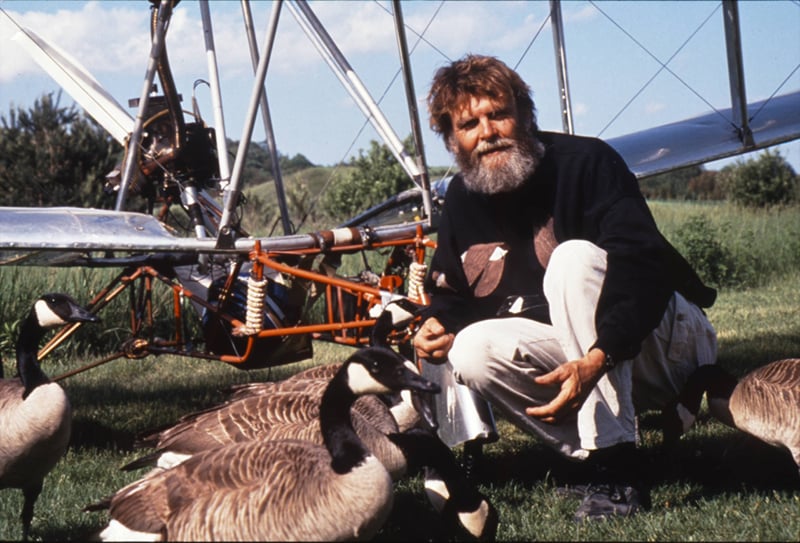

That was Father Goose: impulsive, confident, nonlinear, fearless and a whole lot of fun, and those around him were usually happy to follow him to places on the map that said “There be dragons.” And throughout his nearly four score years (he died just 44 days shy of his 79th birthday), he was richly recognized for his trailblazing ideas, particularly his singular work with geese and cranes — not that that mattered to him.

He held honourary doctorates from the Ontario Institute of Technology and Niagara University in New York State. He was a Fellow of The Royal Canadian Geographical Society and a Fellow International of the Explorers Club. In 2016 he was awarded the Stefansson Medal, the Canadian Chapter’s highest accolade, for his “exemplary lifetime accomplishments and groundbreaking innovation.” And at the height of his worldwide fame as Father Goose, he was awarded the Governor General’s prestigious Meritorious Service Medal for bringing honour to Canada for his pioneering work with migratory birds. He left behind a remarkable legacy of books, films and public artworks, and people all over the world who he inspired in one way or another, sometimes flamboyantly but more often in his own quiet and inexorably arresting way. He was at heart a humble man, who’d be squirming a little by now if he knew you’d read this far.

Bill Lishman wormed his way into my heart for all of those reasons. Since our first explosive encounter, I had the pleasure of working and travelling with him over a number of years with Adventure Canada and with Ottawa-based Students on Ice. The last time we sailed together, just a couple of years ago, he had cooked up a novel concept for energy-efficient and socially sensible housing for Canada’s Arctic communities. Travelling with a cameraman, at each stop along an eastbound Northwest Passage itinerary, he would find the mayor or local indigenous councillors of the community. He’d sit them down wherever they were — indoors, outdoors, it didn’t seem to matter. He’d show them his idea and then sit back and listen to their reaction and response. But between times — and this is the beauty of travelling together on a ship — he was just Bill, and as the journey progressed, we’d find opportunities to converse, exploring ideas and places on the map but also in the near and far galaxies of his imagination.

Father Goose had the most attractive and engaging humanity and humility about him. He was grounded in place and in family. He was comfortable in his own skin. He was genuinely curious about everything under the sun. He could listen. He could laugh. He could dream out loud. He could enact those dreams — the more implausible and impractical the better. He could always find a story from his rich and often chaotic trove of tales that he could weave into yours, without so much as a whiff of narrative one-upmanship. There was always a vibrational energy about him that powered conversation, but there was never the sense that he was in a hurry or easily bored, as long as the ideas were fresh and the banter kept rolling.

It was in this context, one fine Arctic afternoon, that we bounced from his nascent ideas about the design for an aluminium iceberg to be installed outside the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa and onto star stories, myths, tropes and archetypes, which—as it did with Bill—caromed somehow into the fact that at some point he’d carved a piece of ice into a hand lens, polished it lovingly with the warmth of his hands, and focussed the sun’s rays to start a fire. Fire from ice. Really, Bill? Really.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

Environment

The uncertainty and change that's currently disrupting the region dominated the annual meeting's agenda

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

Celebrating iconic collaborations, exciting partnerships, a new RCGS president and many more memorable moments from the 93rd College of Fellows Annual Dinner