People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Ask someone today about the Dawson City film collection and they most likely won’t have a clue what you’re talking about. But in 1978, when more than 500 reels of nitrate film were discovered in an old swimming pool under a parking lot, the unusual story made headlines around the world.

The films, dating from 1908 to 1922, had been screened at the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association, an athletic complex and makeshift theatre that opened in 1902. The film reels were stored in the basement of the town’s Carnegie Library, where they collected dust until 1929, when the athletic association decided to use them as fill to help convert their swimming pool to a hockey rink. They sat in the permafrost for nearly 50 years, surviving even the fire that destroyed the old athletic complex in the 1930s, until they were unearthed during construction of Dawson City’s new recreation centre, and sent to Library and Archives Canada and the United States Library of Congress.

In 2013, New York-based director Bill Morrison decided to use the footage to create Dawson City: Frozen Time, a film that explores the history of the Gold Rush town alongside the history of the 35-mm films. Canadian Geographic spoke to Morrison about his film and the strange story of the Dawson City collection.

On first hearing the unusual story

People who are older than me would remember it as a news story from 1978 and 1979. I caught wind of it in the late 1980s, though it was already hearsay at that point. In some ways, the story was so bizarre that it eclipsed the contents of the find. People were content just to tell this crazy story, but the fact that there were 533 reels uncovered went unexamined. They have of course been catalogued and archived, but there has never been a scholarly investigation of the reels.

On coming across the collection at Library and Archives Canada

In early 2013, I met Paul Gordon, Senior Film Conservator for Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa. He invited me to come check out the Dawson City collection. It was in absolutely pristine condition. They hadn’t been viewed that often, I could tell. These reels exist nowhere else; all other existing reels in the world went up in flames, were ruined by neglect, nitrate decay, etc. These are the survivors. I hope people are inspired by my film to look at the collection and research it using their own skill sets.

On finding rare footage of the contentious 1919 World Series

Very early in my research, in 2013-14, I found footage of the Chicago White Sox from the 1917 and 1919 World Series. To find a five-minute-long, 35-mm original print nitrate of the game was unheard of. In Frozen Time, I slow down a key play that was used in court testimony to show that the games were fixed. That type of examination of the game wasn’t thought possible and set the baseball world on fire for a few weeks.

On finding news broadcasts

Part of what’s so compelling about the collection are the newsreels that date from 1917, 1918 and 1919 — almost 100 years ago. It’s incredible how the news of that time echoes the news of our time, especially American news. In the footage, there are race riots in Missouri, a bombing on Wall Street, a standoff between militants in Colorado. You see that the seeds of what’s happening in the United States today were planted long ago and that’s both depressing and enlightening.

On using local historians to piece together the story of the films

Michael Gates, a journalist, and Kathy Jones-Gates are a couple from Whitehorse who lived in Dawson City and were involved in the discovery of the films. They had photographs of the find, so initially I approached them with a simple licensing request. But I discovered that they are avid historians who cared deeply about the story and Yukon history. One of the themes of the film is how knowledge is stored and passed on from generation to generation.

On the ‘cultural amnesia’ surrounding the films

After the rink and theatre burned down in 1937 and the rink was rebult in 1938, filmstrips started to ooze up from the land. Local kids would set the highly flammable nitrate strips on fire. There was a newspaper story from 1938 warning people not to do that. In that newspaper account, which was only nine years after the films had been buried, there was no recollection of why they were put there. It was written off as something that must have happened long ago in Gold Rush times. Already, in under a decade, the cultural amnesia had set in. I think that’s the nature of memory and history.

Watch the trailer for Dawson City: Frozen Time below:

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

The history behind the Dundas name change and how Canadians are reckoning with place name changes across the country — from streets to provinces

Environment

Canada's largest cities are paving the way for more eco-conscious commuting choices

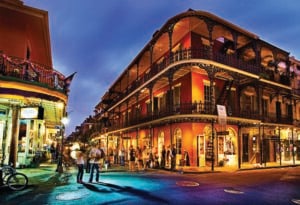

Travel

A tour of the Big Easy’s distinct neighbourhoods offers plenty of insights into the city’s storied past