Mapping

Mapping COVID-19: How maps make us feel

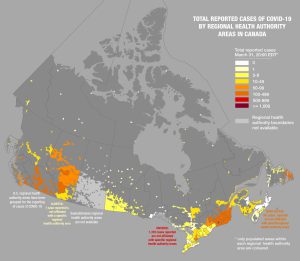

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps

- 1145 words

- 5 minutes