Science & Tech

The Anthropocene is here — and tiny Crawford Lake has been chosen as the global ground zero

Hidden beneath the surface of this Ontario lake is an archive of the earth’s history sealed in mud

- 1670 words

- 7 minutes

People & Culture

The geology professor is a key mover and shaker in what is possibly the biggest geological announcement of our generation, with Ontario’s tiny Crawford Lake being chosen as the global ground zero Earth's most recent geological time period

Update: Since this story’s publication, the governing body for geologists has agreed that the Anthropocene epoch will not be added to the timeline of Earth’s history. On March 20, 2023, the International Union of Geological Sciences announced that it is upholding a decision made earlier this month by a group of geoscientists. In early March, the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, voted 12 against, four in favour and two abstention to reject a proposal that would have established the current era, in which humans are altering the planet, as a formal epoch in Earth’s geological timetable.

Francine McCarthy toast of the world’s geologists, is sitting on a bench beside the lake that made her famous, talking about how she never wanted to be a geologist.

Face shaded by a wide-brimmed hat, sapphire-blue-polished toenails peeking out from workaday sandals, she’s already had one major press interview this morning and has to grab lunch before a third. But you can tell she’s relishing telling the tale.

It was art school that called to her, she says. She wanted to study environmental design. But then, with marks so high they were “off the charts,” she got a generous entrance scholarship to Dalhousie University in Halifax. So she decided to take it, but to enrol in credits she could transfer back to the art college after that first year. One of those credits was a geology class.

“And I’m thinking to myself,” she says, “geology is the science that in my high school the stupid kids took because they couldn’t pass any other of the sciences, right?”

Her sister (who was not stupid) took geology in high school, she recounts, warming to her story. “And she said to me, the teacher gave a hands-on quiz — you know, what’s this rock? And there was one sample that was a Timbit, literally a Timbit, and a lot of people thought it was a rock!”

Suffice to say she had quite low expectations.

Then came the surprise.

Geology “asked questions that I hadn’t even really thought of as questions, like, why are the Rockies where they are? I hadn’t even thought to ask myself that question. But then it gave you the answer!” she says, voice rising in excitement. “I was, like, holy sh*t! You can get answers!”

At the end of the first semester, the geology professor sidled up to her at the back of the lab and asked what her major was going to be. Oh, said McCarthy, I’m headed to art school. His jaw dropped. He told her she had a talent for geology and, maybe, could she reconsider?

A fair few twists and turns later, she ended up here, at Crawford Lake. It’s about an hour’s drive from Toronto and about the same from Brock University, where she is a micropaleontologist in the Earth sciences department. She’s humped down the trail to this lake maybe 50, maybe 100 times, she says, and drilled frozen cores from its depths.

She’s put together an international team of about 75 scientists to examine those cores in the most minute possible detail, published papers on the findings and stated her case in meetings of the Anthropocene Working Group of the International Commission on Stratigraphy.

Now, on this early July day, she’s mere days away from flying to Europe to make what is possibly the biggest geological announcement of her generation and certainly the most widely reported: since the 1950s, humans have pushed Earth irrevocably into a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene, and the best example of it on the planet is right here in this tiny Ontario lake. Geologists refer to that example as the “golden spike.”

It’s not a done deal. Three more committees of geologists have to vote on the evidence, and some of them are chary. But if McCarthy and the others on the working group have their way, her global community of colleagues will eventually proclaim that the planet has entered the Crawfordian age (by protocol, named after the location of the golden spike) of the Anthropocene epoch. It will be only the 39th epoch proclaimed in the planet’s 4.6 billion years of life.

It’s huge. It’s a signal that human activity has irreversibly shaped Earth’s fate, altered its metabolism, set the stage for old species to die off and new ones to evolve. And, like all the asteroid hits, tectonic plate convulsions and volcanic eruptions of the past, that activity is written in the unforgiving archive of the planet’s crust.

“The dawning of the Age of Aquarius,” McCarthy says, a little sombrely, summoning the 1960s anthem of cultural revolution. “Craw-FORD-i-an,” she sings, her voice rising to match the tune, and then the excitement rises again, too, and she begins to chuckle.

The idea of the Anthropocene, which translates from Greek as “the new age of humans,” first took hold in the scientific imagination at an international meeting studying global change held in Mexico in 2000. That’s when the Dutch atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen blurted out the words: “Stop it! We are no longer in the Holocene. We are in the Anthropocene!”

He was referring to the work of the obscure geological discipline of stratigraphy. It is made up of scientists who catalogue the evolution of our planet over time by painstakingly examining the layers of its crust. The field arose in the 19th century as geologists began to realize that life on the planet was not laid down in six literal days by God. Instead, it had been different in earlier eras, and the crust could tell them what and who was there.

The result of their scholarship is the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, a geological time scale published by the International Commission on Stratigraphy. It divides Earth’s history into time periods, the longest of which are eons. (There have been only four.) Like any time-keeping system, the longer units are divided into smaller and smaller ones. But in the case of stratigraphy, the units are not uniform, like days and hours, but rather vary according to the often violent events both within the planet and outside it that shape living conditions. So the eons are divided into eras, which are divided into periods, then epochs, then ages. Typically, the beginnings of ages and epochs are marked with a golden spike, a literal brass marker affixed to the best representative of the transition from one geological time unit to the next.

According to this system (and until the three more levels of stratigraphers endorse McCarthy’s case for Crawford Lake), we are officially in the Meghalayan age of the Holocene epoch of the Quaternary period of the Cenozoic era of the Phanerozoic eon. Try saying that three times fast. So when Crutzen erupted at that meeting in Mexico, he was calling on the world’s scientists to acknowledge that the world had changed so much at the hand of humanity that the Holocene epoch had ended. A new geological time unit had begun: the Anthropocene.

Stratigraphers are not moved by outbursts, even from such eminences as Crutzen. (Crutzen shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1995 for explaining the ozone hole, a risk to life on the planet, and had his finger on the pulse of Earth’s life-support systems until he died in 2021.)

Instead, stratigraphers pondered. In 2009, they finally set up the Anthropocene Working Group, an interdisciplinary gathering of about three dozen scientists tasked with examining the evidence, including a possible start date for the new epoch. Was it, as Crutzen suspected, when the first coal-fired engines sputtered to life in the middle of the 18th century spawning the Industrial Revolution?

By 2016, most of the members of that working group agreed that the Anthropocene was stratigraphically real and that it began in the middle of the 20th century along with what’s known as the Great Acceleration. That’s the period after the Second World War when Earth’s human population surged. So did industry, driven by burning fossil fuels. That loaded the atmosphere with carbon dioxide and other carbon-based gases, disrupting the climate system. Add to that plastics, nuclear tests, nitrogen-based fertilizers and species depletions, all laid down in the crust.

It represents a point of no return, geologically speaking: the end of the Holocene epoch that began during the Stone Age about 11,700 years ago and whose long climate stability supported the growth of human civilization.

“It is very unusual,” Martin Head, a biostratigrapher at Brock University who sits on the Anthropocene Working Group, said in an interview. “In fact, in many ways, it’s absolutely unique. The planet has already left what you might call the envelope of natural variability that characterizes the Holocene.”

The carbon concentration in the atmosphere is also higher than the range that characterizes the longer Quaternary period that began some 2.58 million years ago, he said. That means the planet has also breached the norms of that longer geological age, another piece of evidence of just how far humans have altered Earth. “So we really are pushing the boundaries here. The planet is moving into uncharted territories. There’s no question.”

Some of the other transitions in the geological time scale abruptly affected the planet’s ability to support life. The asteroid that hit Earth 66 million years ago killed off the dinosaurs, for example, launching a new era. This transition is different from those that contorted the crust, explained Simon Turner, secretary of the Anthropocene Working Group and a senior research fellow at University College London.

“The effects are very much atmospheric, soil. Essentially, the living parts of the planet are what have been so massively affected by the Anthropocene,” he said in an interview from London. “And in that sense, it is on a par with some of these major planetary events that have occurred in the past.”

The first time McCarthy visited the part of Canada that is home to Crawford Lake, she was about 10. Her extended family was travelling from Montreal, where she grew up, to Niagara Falls, a common trip at the time for French-Canadian families. “It’s a thing,” she says, laughing. She’s eyeing a small group of visitors navigating the boardwalk around the lake as she talks, waiting to see if they need her help. They move along, and she takes up her story with gusto.

On the way, McCarthy’s family stopped to savour the Hamilton skyline because her father was a huge fan of the Tiger-Cats, the local football team. “To him, it was like going to Mecca,” she says.

But all McCarthy could focus on was the smokestacks of the open-hearth blast furnaces, which at that time, the early 1970s, made steel out of iron by burning coal. Schooled in the work of Rachel Carson, the environmentalist who described the perils of using the pesticide DDT in her 1962 book Silent Spring, McCarthy began to cry. “It’s so ugly,” she told her family. “It’s so ugly.”

It’s a prophetic story. Some of the carbon particles McCarthy saw spewing into the air that day ended up in Crawford Lake, carried there, like Hamilton’s other industrial residue, by prevailing westerly winds. Decades later, they helped McCarthy and her team make the case that Crawford Lake is the best example in the world of the start of the Anthropocene.

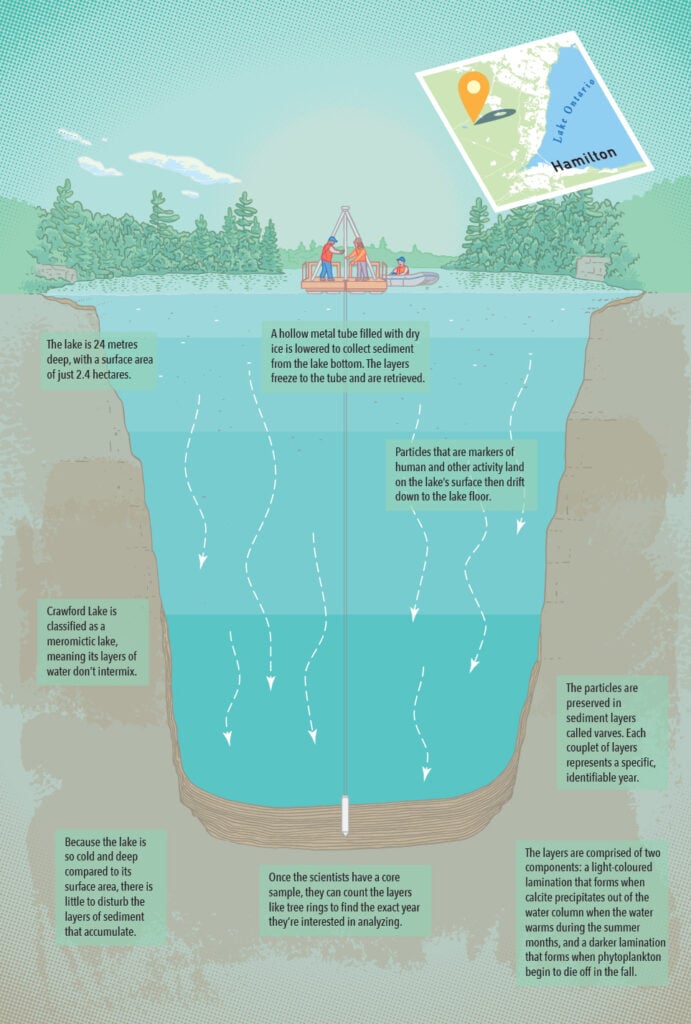

The proof lay in the chemistry of the lake itself. Crawford Lake is meromictic. Its surface area of 2.4 hectares is small compared with its depth of 24 metres. That means the top layer cannot mix with the bottom. Originally, scientists thought the lake lacked oxygen. But actually, it is aerated. That makes Crawford Lake the only oxygenated meromictic lake scientists know of in North America and one of the few in the world.

The result is that sediments are laid down in perfect, undisturbed couplets of layers called varves, sealed by deposits of calcite each summer and each winter. These laminated layers are like tree rings. Each couplet represents a specific, identifiable year going back a millennium. And each couplet contains evidence of what was going on in the world above the lakebed.

“It’s like looking into the memory of the planet,” Hassaan Basit, president and chief executive of Conservation Halton, said in an interview. The private organization owns the 222-hectare conservation site containing the lake. The site is part of the Niagara Escarpment UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

For the first few years after the organization bought the lake in 1969, examining the cores was exciting simply because the lake is so chemically rare. Then, in the 1970s, the researcher Maria Boyko-Diakonow discovered corn pollen in layers from the Middle Ages, centuries before colonization. It was a surprise to western science, proof of agriculture before settlers knew the New World existed. And it led to the archeological discovery of intricately crafted longhouses dating from the 15th century. Three replicas now stand on the site a short walk from the lake, along with interpretive displays of the crops that supported the community then, developed in partnership with the Ojibiikaan Indigenous Cultural Network and Miinikaan Innovation and Design.

McCarthy became involved in 2011 when a graduate student began to study one of the cores that had been drilled from the lake bottom. Her colleague Martin Head, the bio-stratigrapher, was on the student’s thesis committee and came to know about those varves. He has a long involvement with the International Commission on Stratigraphy, which sets the geological timescale. Plus, he was on the Anthropocene Working Group that, in 2019, launched the global quest to find the golden spike. What about Crawford Lake? he asked McCarthy.

“And I said, ‘sure,’ and the rest is history,” she says blithely.

She put off planning for retirement and began assembling “Team Crawford.” Chief among the experts was Tim Patterson, professor of Earth sciences at Carleton University in Ottawa, with whom she had studied at Dalhousie. He is a specialist in taking freeze cores from lakes, a process critical to getting perfect, precise layers from Crawford Lake.

“I knew if I needed a lot of freeze cores, Tim was my man,” she says.

The sediments are fragile and filled with gas. If brought up without freezing, they explode. So Patterson perfected a technique that involves filling a corer with dry ice to freeze its metal face. In the lake, sediments dating back 1,000 years freeze against the face and can then be brought up to the surface and analyzed, as long as they are kept frozen.

Then Patterson’s student, Krysten Lafond, figured out how to make very high-resolution images of the layers, stitch them together and enlarge the composite to the size of a house. That allowed extremely precise identification of each year of calcified sediment.

The dramatic planetary shift shows up in about 1950. Among the clues: those carbon-based particles from the steel mill in Hamilton, a change in nitrogen isotopes from fertilizer use, the chemical fallout from acid rain, a shift in the species living in and around the lake, and plutonium from above-ground nuclear tests.

Even more remarkable, samples from the other 11 candidate golden spike sites around the world — they span five continents and include Antarctic ice, tropical corals and mountain peat bogs — show the same markers of human activity with extraordinary consistency.

“When you combine them and read the stories that they tell you, it shows you that there is this very significant and very rapid change to the environment in a very short period of time,” Colin Waters, a geologist at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom, explained in a press conference. He is chair of the Anthropocene Working Group.

It took three rounds of voting at the working group for Crawford Lake to emerge the winner. The runner-up was Sihailongwan Maar Lake in China. It also features varves.

The research on other candidates for the golden spike will bolster the case that McCarthy, Head, Turner, and Waters and the rest of the Anthropocene Working Group have to make over the coming year to convince colleagues that the spike is merited. They hope the new epoch will be named next summer at an upcoming international geological conference in Korea.

But that’s just one of three possibilities. The other stratigraphers could quash the whole idea of the Anthropocene. Or they could proclaim the Crawfordian age but insist that it is part of the Holocene epoch. Members of the Anthropocene Working Group know that some stratigraphers are vehemently opposed to proclaiming the new epoch. It’s hard for scientists who are used to working with the deep past to look at the evolving present.

McCarthy is pumping for the new epoch because she can see right here before her own eyes the terrifying archive of abrupt planetary change, sealed in the mud. She’s proud of the team she assembled and of all the hard work they did. As she sits by this soon-to-be-famous lake, the press conference in France to announce to the world that Crawford Lake is the golden spike candidate is just days away. When the Anthropocene Working Group’s block-buster declaration is made on July 11, she will get a little emotional. “I really revelled in the entire experience,” she’ll tell the assembled crowd. “It’s the best thing I have ever done.”

But that’s still a few days away. And the next round of scientific discussions about the golden spike are weeks and months after that. Today, she’s here, at this weird little lake, basking in the culmination of years of effort, trying to get the message out about what our species has done. She says it’s the only way she can sleep at night.

“Somebody has to take the high road,” she says. “Somebody has to be the leader.”

And then she has to go. Still explaining, she strides up the trail from the lake to the car park to dash off for lunch, two students in tow, before yet another interview today and many more in the days to come. Knowing what she knows, she can’t just sit back and do nothing.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the November/December 2023 Issue

Science & Tech

Hidden beneath the surface of this Ontario lake is an archive of the earth’s history sealed in mud

People & Culture

Uprooted repeatedly by development projects, the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree wandered boreal Quebec for 70 years before finding a permanent home. For some, the journey continues.

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it