Environment

Inside the fight to protect the Arctic’s “Water Heart”

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

- 1693 words

- 7 minutes

People & Culture

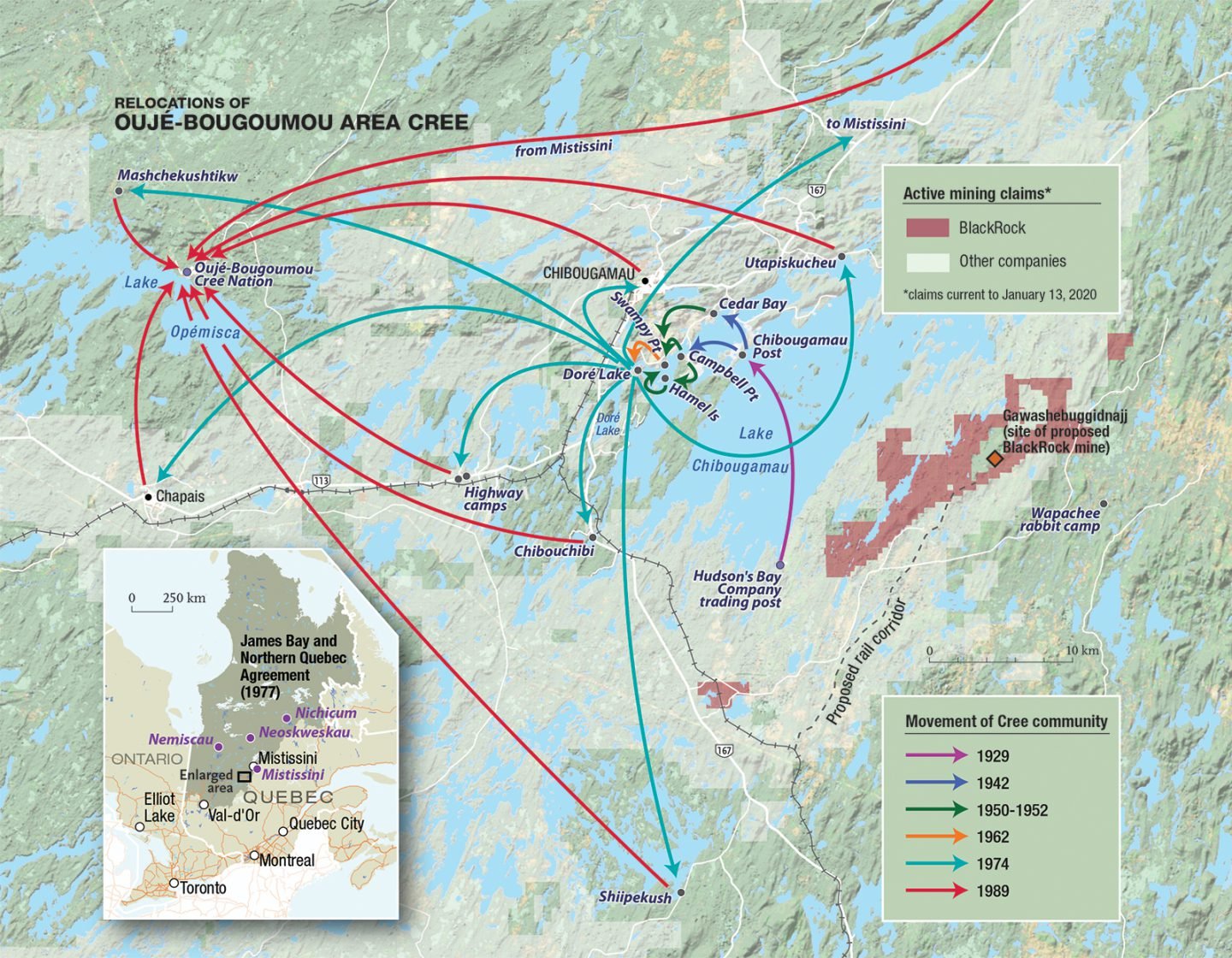

Uprooted repeatedly by development projects, the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree wandered boreal Quebec for 70 years before finding a permanent home. For some, the journey continues.

Abel Bosum, Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees, plants his dress shoes where his parents’ house once sat on a thin wooded spit that curls into Doré Lake like a dog’s tongue into a bowl of water. A late September breeze rushes through the birch trees. Bosum’s mind turns to the past. This was the site of the final village from which his people, the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation, were uprooted by a mining company — this one a gold pit owned by a fellow named Campbell — in the unrelenting pursuit of monetizable minerals from the Canadian Shield.

The Bible says the Israelites wandered the wilderness for 40 years before Moses led them to the Promised Land. The Oujé-Bougoumou Cree roamed the boreal near what is now the town of Chibougamau, Que., like squatters, seeking shelter in roadside shacks, miners’ tents and trapline cabins for some 70 years before Bosum led them to secure a permanent reserve on the shores of Lake Opémisca, about an hour’s drive from here, in 1992. For some, the exodus might not be over.

Bosum was born in 1955 at nearby Lake Chibougamau, separated from Doré Lake by a thin isthmus across which the Cree could easily portage their canoes. He was the eldest of his mother Lucy’s 11 children. Lucy’s parents forbade her marriage to Abel’s biological father, Cypien Caron, a French-Canadian, and so Lucy instead married Sam Neepoosh, who was a father figure to Abel. Standing where his childhood home once did, Bosum surveys the lakeside peninsula. This is his first time back since the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree hosted a healing camp on this plot 20 years ago. Today, it’s the site of a small family farm with chickens, rabbits and a lone cat. When Bosum and I stop in, the owners aren’t home, so technically, we are trespassing.

“I’m still amazed at those trees,” Bosum says, scoping out the paper birch outside the modest two-storey house. Bosum recalls a photograph taken of his aunt in front of one of these trunks. There’s another, somewhere in the memory books, of Bosum posing outside his family’s cabin in a pair of DIY bell bottoms (made by cutting a slit up from the cuff of the jeans and stitching in an extra triangle of denim), his hair hanging over his shoulders like a hippy. At 63, Bosum’s now silvery hair is close-cropped. He speaks softly and thoughtfully as memories return, periodically adjusting the rectangular glasses resting on the bridge of his plump nose. “That was a long time ago,” he says wistfully.

Bosum remembers log homes built in a circle, their front doors facing inward. About a dozen structures once stood here. The builders would begin by erecting a plywood shack with a tarp for a roof. Over two to three years, using materials rummaged from a nearby dump, families slowly built up walls and roofing before sealing windows, adding insulation and finally fixing up the interior. “It wasn’t like today,” says Bosum. “We had no credit, couldn’t go to the bank.” Nonetheless, families took pride in their homes, at least in part because they were under the impression that, if they built up a dignified community, the provincial and federal governments would let them stay.

In the centre of the village, roughly where the current residents now have a front-yard firepit, there was once a makeshift ballfield. A baker used to stop to sell bread and Vachon cakes out of his van. Families pinched pennies to save for the pastries. One time, Bosum and five young friends organized a cake heist. Their plan was simple: Eddy, the fastest, would pick up a Vachon and run. The baker would give chase. His van abandoned, the other four would make off with as many morsels as they could. The scheme worked and the baker was pissed. After that, the kids weren’t allowed to come around his van anymore. Months later, during a trip to the dump for building supplies, Bosum spotted the man throwing away his cakes after making his final sales at Doré Lake. It was then he realized the breadman had been selling the village the last of his supply as it started to spoil. “That was no favour,” says Bosum.

Behind each house, there was a trail down to the lake, where families kept the canoes they used to traverse the many interlinked waterways spattered across Chibougamau and James Bay like a region-wide Rorschach test left by the retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet millennia ago. Despite the once meagre circumstances of his people, Bosum considers this a place of plenty.

Doré Lake, or Lac aux Dorés in French, is named for the doré (walleye) found in its waters. Blueberries and raspberries grow on the hill above the village. In the 1960s, a Quebec government official told then Chief Jimmy Mianscum that his people could remain here indefinitely. In 1966, the Canadian Centennial Commission even wrote a grant for $1,700 so that Anglican Church volunteers from far-off cities like Toronto could build a 15-metre-long hall for community meetings and religious services at Cache Bay, just around the bend from the village. It doubled as the chief’s home. The villagers called it “Beaver House.”

Bosum remembers a wedding party at Beaver House when he was a little boy. At around 11 o’clock at night, four police pulled up and started throwing attendees into the backs of their squad cars. The Cree were shaken and injured. “Nobody knew what was going on,” says Bosum. “There was a lot of racism back then. There was a lot of tension built up between the Cree and French people working in the mines and so forth. And so, the police — I wouldn’t say all of them, I knew some good police — but there were some police who would use their authority to just come in and crash a party. They weren’t even invited and they weren’t called.”

***

For most of the 1900s, Cree life was organized around the harvest of fur, timber and minerals for French- and English-speaking colonists who first appeared in the region in the 1600s, as well as an older Indigenous subsistence economy. In 1870, the Canadian Geological Commission sent a surveyor to the region. Gold was first discovered in 1903 at Copper Point on Portage Island in Chibougamau Lake. The Cree maintain that their ancestors, who didn’t know the value of the metals, first identified outcroppings to prospectors. A series of mining booms and busts followed, generally tracking global economic cycles: down with the crash of 1929, up after the Second World War. In 1947, the Quebec government began construction of a road into the region. It was completed by 1950, and loggers began chopping away at the spruce that grew dense, strong and tall in the backcountry. When Chibougamau was established as a company town in 1952, there were 25 sawmills operating in the region producing 50 million feet of timber, primarily for export to the United States. In 1954, the province incorporated Chibougamau as a municipality.

The Cree, who had the misfortune of building homes on top of riches claimed by white men, were displaced from village after village. And even when they weren’t removed by industry, they felt its impacts. Piles of mining garbage left atop frozen lakes in winter killed fish and ruined drinking water in summer. New mines, logging plots and roads scared off game. In the years before they established themselves at Doré Lake, the Cree lived at Hamel Island, Swampy Point, Campbell Point and Cedar Bay, among other places. At Hamel Island, they were told to move because the government needed sand to build highways. At Swampy Point, the only land not claimed by prospectors, influential clergymen cited public health concerns before telling the Cree to hit the road. At Cedar Bay and Campbell Point, the Cree were told their homes were too close to mining explosives. Each time they were uprooted, they had to find a new place to settle, clear-cut a lot and start building a new shelter. When they left Campbell Point, they had to dig up and relocate the remains of ancestors interred in a community cemetery. Many turned to alcohol to cope.

Beginning in 1962, most had summer residences at the village on Doré Lake. Men would join prospecting teams, working as explorers and line-cutters felling trees in areas of interest for mining corporations. Others found jobs as lumberjacks. They drank the water and ate the fish from the lake and supplemented their incomes with rations and welfare collected from government officials at a Hudson’s Bay Company post on the Mistissini reserve, about four days’ voyage by canoe. In the fall, families returned to camps where they trapped beaver, otter and lynx to sell to the Hudson’s Bay while they hunted moose, goose, caribou, bear, porcupine, rabbit and partridge to eat. Between 1952 and 1972, the white population of Chibougamau grew from fewer than 200 to nearly 12,000. They far outnumbered the Cree at Doré Lake, whose population was about 125 in 1968.

Bosum remembers when, in 1962, his mother and stepfather took him on one of their trips to the HBC post in Mistissini. At the store, Bosum’s mother bought her boy the finest clothes she could afford. Bosum remembers the pride he felt, looking at himself in the mirror. The next day, a plane landed on Lake Mistissini. Bosum’s stepdad Sam said, “time to go” and walked the seven-year-old down to the dock where Cree children were gathered. A white man stood before them, calling out names to be loaded onto the aircraft. Bosum’s name was called, and his stepfather carried him to the hold alongside 30 other children. They would be the first students of the La Tuque residential school run by the Anglican Church hundreds of kilometres south. The children cried as the plane carried them away.

That same year, despite repeated promises from both the provincial and federal governments to respect their village and build new homes, the Cree at Doré Lake, along with others from Neoskweskau, Nemiscau and Nichicun, were incorporated under the Mistissini Band by the Department of Indian Affairs. Government and industry compelled the Cree to abandon Doré Lake. Finally, when the Campbell firm discovered a new deposit near the village, the Cree caved. “At Doré Lake, we were told to move to Mistissini — that the land belonged to the white men,” Mary-Ann Bosum, a local Cree, told anthropologist Jacques Frenette in 1982. “This was not true. The land was my father’s hunting territory, and his father had hunted there, too.” Others, like Bosum’s mother Lucy, relocated to the town of Chibougamau. Some went to Chapais. The community, once gathered around the lake, the Beaver House and the ball field, dispersed.

The last Cree families departed Doré Lake in 1974. Their log homes and the Beaver House were demolished soon after. The Campbell mine operated for three years.

Maggie Wapachee, 88, is skinning a beaver that is lying belly-up on her kitchen table, when her son Norman walks in the front door. Earlier that morning, Norman’s father Matthew, 87, trapped and killed the animal before retiring to his room. Maggie speaks Cree exclusively, so Norman translates for me as she sets about flaying the critter. “I’m getting old for this kind of job. I can’t work as fast as I used to,” she says in her percussive Eastern Cree dialect — pointy vowels wrapped in round, repetitious consonants. (Say “Chibougamau” and you get a taste of its phonology.) Norman chuckles as he offers the translation.

The beaver, a Cree staple, can be broiled in the oven, boiled on the stovetop or roasted over an open fire. Their tender tail is considered a delicacy. But they’re also pungent when they cook, and Maggie, a gracious host, says she wants to spare our nostrils. “I would never stop doing these types of activities, because I love it,” she says as she takes a break from her work. “My late mother taught me these things, so I just want it passed down to continue this way of life.”

Still outfitted from his early morning moose hunt, Norman points out the back of the house at the Chibougamau River, which moves at a slow crawl. There, most of his 14 siblings — six boys, six girls, plus two adopted sisters — had their walking-out ceremonies, a Cree rite of passage marking a child’s first steps. The mother and grandmother walk baby girls out into the water; grandfathers and fathers walk out baby boys. “It’s a commitment that they will raise the child, introduce the child, in the Cree way of life — that the child will be raised out on the land to maintain cultural tradition,” explains Norman. “It’s been done since time immemorial.”

The Wapachee family has lived here at Chibouchibi on the Chibougamau River for decades. After leaving Doré Lake, they lived in Mistissini for 10 years. When the Oujé-Bougoumou reserve was established, Matthew, the Wapachee patriarch, opted instead to build a house on the family trapline, which runs more or less perpendicular to Highway 167, the main thoroughfare built after the Second World War to connect Chibougamau’s mines and lumberyards to the rest of the world. (Chibouchibi is located right on Highway 167, while the turnoff for Oujé-Bougoumou is 20 kilometres west down Route 113, which transects the highway south of Chibougamau.) The Wapachee clan, who now number some 140 children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, maintain a traditional way of life. Their seasonal hunting grounds extend deep into the bush to the southeast along Logging Road 210 to a mountain called, in their stories, Gawashebuggidnajj (pronounced “Ka-wa-she-pi-ki-ti-nach”), which roughly translates as “Gold” or “Bright” Mountain, so named for the birch trees that grow on its slopes and shine from a distance. That’s where the Wapachees can most reliably spot and hunt browsing moose. “It’s where we feed our children and our grandchildren,” explains Maggie.

BlackRock Metals Inc., however, wants to level the mountain to create a giant open pit titanium, vanadium and high-purity iron mine. In 2013, the Grand Council of the Crees and the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation signed an impact benefits agreement with BlackRock. The agreement, named for Bally Husky, one of the Wapachee ancestors who hunted this land, promised to provide money, jobs, training, business contracts and environmental monitoring opportunities to the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation. Norman has even worked as BlackRock’s community relations coordinator.

BlackRock plans to break ground once the company secures more than $1 billion from investors. As of 2018, the company had raised about a third of that, including $63 million from the Quebec government to support infrastructure upgrades at Port Saguenay so BlackRock’s products can be exported to China. But the mine has been delayed by mineral price fluctuations, and in the interim BlackRock seems to be rolling back some of its commitments.

Critics of the project in the Wapachee family and the community say there will be fewer jobs and contracts available to the Cree than originally promised. Meanwhile, early exploration and construction have been more disruptive to wildlife, the environment and the Wapachees than anticipated. Before BlackRock opens, for example, the Wapachees will have to relocate their rabbit camp — the cabins they use for the fall and winter hunt. “The relocations have not stopped yet,” explains Norman, who is clearly conflicted about the mine but feels he has little power to stop it. “We have camps over here that we use seasonally for our main hunting activities. BlackRock company came in, and now what’s challenging for the Wapachee family is that we’re being asked to relocate those camps.” He continues: “It’s been repetitious, how the government works: opening doors for further resource development.?… Our hunting areas in the trapline are getting smaller and smaller, and so this is where we look at what are we going to do.”

Roused by the commotion of company, Norman’s father, Matthew, emerges from his room. “He’s upset with me,” says Norman under his breath, before skedaddling out the front door.

***

“We’re in trouble!” yells Matthew. “We’re in trouble on the trap-line!” Stout and cantankerous with bushy eyebrows poking out above thick black glasses, Matthew uses a beaded belt to hold his grey trousers aloft. He plops himself down at the head of the kitchen table, the half-dressed beaver still resting there.

Matthew was once tallyman, or manager, of this trapline, but has since passed that responsibility to his eldest son, Phillip. Matthew is opposed to BlackRock. But it’s a more complicated story for his children. While all express misgivings about the desecration of familial territory, some feel that development is inevitable and that they must make the best of bad circumstances.

A few, like Norman, have even chosen to work with the company. But by doing so, Matthew feels the children have circumvented his and Phillip’s authority. It’s not that Matthew is categorically opposed to development — in fact, he was one of the first Cree miners in the community. But as the land becomes increasingly bare, his sense of loss and bitterness grows. He chose to build his home out here. And now, in his old age, it’s being taken away from him. “I’m going to win,” he says in a later conversation. “The BlackRock, they’re not going to start this mine while I’m still alive.”

Once Matthew settles down, Maggie heads out to the back porch, bundled up in a jacket with a red sweater underneath, Cree florals embroidered on its left breast. Maggie’s daughter Cynthia joins us to translate, plunging her hands and bespectacled face into a green hoodie to stay warm. Maggie has birdfeeders set up on the deck. Generations ago, in a time of hardship, Matthew’s father Alan had to kill and eat small birds to avoid starvation. The warblers that frequent their home serve as a reminder of the family’s survival.

“I love it here,” says Maggie, a wisp of grey hair hanging in front of her ear, the corners of her eyes curled toward the sky in a slight smile as she speaks. “I hope for my children to have stability in their lives and not have to go through what I went through in having to move from different places.”

The Cree way of life is one of survival. Unlike most Cree people her age, Maggie did not attend the residential school and instead learned the skills of Cree womanhood from her mother in Mistissini. Before she could marry, she needed to know how to skin a beaver; how to scrape, stretch and smoke a moose hide; how to make clothes and moccasins out of the leather; how to knit a fishnet; how to clean an animal and a house.

Once she learned these things and more, a marriage was arranged with Matthew, who lived in Doré Lake. But there, Maggie recalls that the couple was surrounded by hardship and alcohol. Maggie’s own father, William, was a drinker. And as she tells the story, Maggie, an animated speaker, sticks out her chest and boisterously swings her arms, pretending to take a deep swig from an imaginary bottle. (She’s a favoured orator at community functions for obvious reasons.) Maggie credits tradition and the Church — which she doesn’t see as incompatible — for setting her family and the community on a different path. She’s devoted to both. “When we became Christians — that’s when I found peace in my home,” she says. “We’ve got to continue our way of life — it’s like you drop something,” she stretches out her fist and opens it, as though an object is slipping through her fingers, “it’s hard to pick it back up.”

The divisions sown by BlackRock weigh on her. At the time of my visit, Norman, Phillip and Matthew aren’t speaking. With her husband and children at odds, Maggie, the matriarch, has to hold things together. “She’s like a needle,” says her youngest daughter, Alice. Like Matthew, Maggie is concerned BlackRock has caused the Wapachees to lose their way. Sitting on the back porch, Maggie looks out at the water where her children took their first steps in the Cree way. “I have good memories of the past,” she says. “The environment, where I am, how I see it now — it hurts.”

Back inside, Maggie finishes skinning the beaver. She demonstrates how to use a willow tool to make a fishnet and shows off the moccasins and gloves she makes with smoked moose hide. Mid-visit, her son James walks in the door wearing a Boston Bruins cap and camouflage sweatshirt. (If there was a Cree sitcom, the Wapachee household would be a worthy set.) James has just spotted fresh tracks out on the trapline. He didn’t see the animal, but he made some moose calls and expresses optimism that the game will return later that night. It is about time for the Wapachee hunters to gather at camp and prepare for the hunt.

Maggie, Cynthia and I wrap up our conversation. Tapwe, she says as she gives me a big hug, rubbing my back while she prays in Cree. The only word I understand — “Jesus” — is peppered throughout her invocation. “Amen,” she says. And although I don’t go to church, I say “amen,” too.

Then Cynthia and I walk out the door and hop in the back of James’s F-150. His .270 hunting rifle rattles beneath my boots as we roll on down the road to rabbit camp.

***

Abel Bosum and I sit on a bench beside the shaptuan, an oblong Cree structure that stands roughly at the centre of the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation’s administrative buildings. The business services centre is to our left and the government offices to our right. The Cree Cultural Institute, a museum, lies directly ahead. The Pentecostal Church is at our backs, and beyond that, Lake Opémisca.

In 1989, the Oujé-Bougoumou built this shaptuan for a signing ceremony with Quebec when the province agreed to contribute funding for the construction of a village and recognized, to a limited degree, the community’s jurisdiction and self-government. Three years later, the Oujé-Bougoumou finalized an agreement with the federal government, securing further resources for their village and setting them on the path to independence. Back then, the Cree lived in shacks down the hill closer to the lake, and the shaptuan was the only structure here.

Bosum recalls the 1989 celebration. It began with a prayer from an Elder and a song from the youth. The Cree feasted on moose, bear, beaver and bannock. Speakers from the First Nation and the provincial government shared speeches marking the historic agreement before signing the document and shaking hands. Bosum, one of the negotiators, remembers people in the crowd crying. “It was quite an emotional journey for many people,” he says of the negotiations. “They come out, they express, they participate, and then sometimes I had to come back and report that things were not going well or that idea is out the window. It was like a roller coaster. But to actually reach a point in the process where you’ve got an agreement, you’ve got the ceremony — well, that was quite an accomplishment.”

Bosum tells the story of how he and his people got to that point. After Doré Lake, Abel’s mother Lucy moved to Chibougamau where she lived on welfare and worked intermittently as a chambermaid. Her husband Sam died in 1969. She turned to alcohol. She remarried. When he was around and his mother was on the bottle, Abel helped take care of his siblings. He remembers the arguments and violence that accompanied Lucy’s addiction, the sound of her sobbing. On weekends, he would leave the apartment with the kids until things died down on Sunday. Child services ended up taking some of them away. Many have pulled through, but some are no longer with us — their lives also consumed by drink and grief.

At the residential school, Abel met Sophie Happyjack from the Waswanapi Cree Nation. When they weren’t in La Tuque together, Abel would hitchhike for two days across northern Quebec to visit her. They had four children: Irene in 1975, Curtis in 1977, Reggie in 1982 and Nathaniel in 1989. Nathaniel, a professional motocross rider, died in a racing accident two years ago. Curtis has been Chief of Oujé-Bougoumou since 2015.

Despite the circumstances of his youth, Abel persisted. After residential school, he worked in the mines. Then he took a course on community planning, communications and government affairs in Elliot Lake, Ont. Every other weekend, he would drive 17 hours back to Chibougamau to be with his wife and young family. (He missed Curtis’s birth by two hours during this time.)

In the 1970s, things were changing in northern Quebec. The province had plans to expand hydroelectric dams on James Bay, but the affected First Nations and Inuit insisted that their rights be respected. In 1975, the Cree and Inuit of the region, as well as the provincial and federal governments, signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, the first modern treaty in Canadian history. It allowed the province to complete construction of the dams and in exchange, it awarded the Cree and Inuit $225 million to be paid over 20 years and recognized their distinct territorial and cultural rights. It affirmed the independence of many Cree and Inuit communities, while incorporating them into the region’s economy. But it left out the Cree from Doré Lake, who were legally subsumed under the Mistissini Cree Nation at the time.

After completing his coursework, Abel got a job in Val-d’Or with the Grand Council of the Crees, a new governing body created to implement the James Bay agreement. His job was to travel to First Nations in the region, communicating

plans and developing economic strategies. His travels brought him back to Chibougamau.

In the 1980s, the Cree dispersed from Doré Lake were being born again. Preachers with colourful names — Enoch Hall, Chuck Morton, Lott Thunder — evangelized the community. Many became Pentecostal. At camp meetings, they studied the Bible, but they also rediscovered who they were and began discussing what had happened to them. Many got sober. In 1984, they elected Bosum chief, and he opened an office in Chibougamau and started leading workshops and sending letters to the provincial and federal governments to petition for recognition. His allies at the Cree Indian Centre of Chibougamau enlisted the aforementioned anthropologist Jacques Frenette to conduct an ethnographic study of the First Nation. Frenette argued the Cree who once lived at Doré Lake were a distinct group, and his book, The History of the Chibougamau Crees, published by the centre in 1985, armed the community with valuable evidence to advance their cause. People, some in high places, started paying attention to these Cree who had been left out of the James Bay Agreement and were living in Third World conditions.

When the Liberals came to power in Quebec in 1985, Bosum saw an opening, but tripartite negotiations between his community, Quebec and Canada were slow and complicated. Quebec’s position, according to Bosum, was that his band could receive land once they had secured federal recognition. The Canadian government’s position was that the Cree could receive recognition once they had land. The negotiations were further complicated by the fact that Quebec sovereigntists wanted nothing to do with the federal government, and Indian reserves were primarily a federal issue. Neither government wanted to compensate the Cree for the $4-billion worth of natural resources that the First Nation estimated had been stolen from their territories since the 1950s — contaminating lands and waters and dispossessing them of their homes along the way.

Bosum remembers one particularly contentious meeting held in a Cree cabin. The federal negotiator had flown in from Ottawa and left a taxi outside the meeting with the meter running. Cree kids built a bonfire nearby. As the hours dragged on, federal and provincial representatives had their aides fetch hot dogs. Finally, around 11 at night, the federal negotiator caved and signed a deal. Two days later, he sent a letter alleging he had been coerced. Negotiations broke down. Bosum recalls advice that Robert Epstein, a friend, gave him: “You’re going to wait on the government forever. If you believe your people are distinct, act like it.”

***

In the summer of 1989, the Cree declared jurisdiction over their territory, established their own court and convicted Quebec and Canada of theft of resources and destruction of villages. They erected a blockade under a transmission line carrying power from James Bay to the United States. “The reporters that came, they were taking pictures with the transmission line in the background. And, of course, that caught Quebec’s attention, because this is their billion-dollar line for their hydroelectric project and here are these Indians underneath,” Bosum recalls, laughing. By September, the First Nation and Quebec had reached an agreement. The federal government followed suit.

After a long diaspora, the Cree set about selecting and designing a permanent village. They began by having each family choose a favoured spot on their trapline. They then worked with community planners to narrow down the selection. The community voted on the final three options and chose the current site on Lake Opémisca. It was a fortuitous decision. Although the Cree didn’t know it at the time, an esker, a ridge of gravel, runs through the land and acts as a natural water filter. The community hired renowned architect Douglas Cardinal, of Blackfoot, Algonquin and Métis heritage, to design their new village according to traditional architectural forms, like the shaptuan, and to reflect traditional values, like sustainability.

All the buildings on the reserve are connected to a central heating system, which burns waste sawdust from local mills to pump heated water. When the community moved into their new houses, after generations of living in shacks, many didn’t even know how to use a faucet or toilet. The most common complaint, Bosum recalls, is that the homes were “too big.” Families named the streets for places out on their traplines: Muskuuchi Meskino for “Bear Street,” Ginshaw Wagumshi Meskino for “Pike Fishing River Street,” Oukauw Sakhegun for “Doré Lake.” They called their nation Oujé-Bougoumou: “The Place Where People Gather.”

The Oujé-Bougoumou Cree, particularly the Elders, still spend much of their time out on the land. The community observes a two-week Goose Break in the spring and a similar Moose Break in the fall. When I visited, the village was mostly empty, as families were away pursuing bull moose on their hunting grounds. But tradition is, of course, a flexible thing. For Goose Breaks, Abel has built a plush cabin with six rooms. On a recent family hunting trip, his grandson told him: “Grandpa, this is not a cabin. This is a hotel!”

Bosum was Chief for 14 years and has been Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees since 2017. His son Curtis was just elected for a second term as Chief of Oujé-Bougoumou. Before interviewing the elder, I spoke with the younger Bosum in his second-floor corner office. From his desk, the Chief can see much of the nation his father built: the Pentecostal Church, the daycare, the youth centre, the tourism lodge, the development corporation and the shaptuan. Beyond that, the lake, the woods and the mountains. At the start of every day, he looks out across his people’s domain. “My morning view,” says Chief Curtis, “really is just a reminder of my duties, my responsibilities, who I’m here for.”

***

At the Wapachee rabbit camp, a row of four cabins crossing Logging Road 210, Cynthia is trying to get a fire going using dry spruce twigs and boughs for kindling, but isn’t having much success. John Blacksmith, her boyfriend from Mistissini, steps in, as men tend to do, but can’t catch a spark. Eventually Cynthia’s brother James comes over with a piece of cardboard doused in gasoline and the fire bursts to life. “Get the steaks!” James yells, theatrically. “Now don’t write we had to use gas,” he says to me.

Once the fire is crackling, Cynthia fetches the moose leg steaks, which she has cut into thin filets and set out to thaw on butcher paper. (These came from Norman’s kill last year. The Wapachees haven’t taken a moose yet this season, as the animals are increasingly scarce on their hunting grounds.) She spears one filet each onto three pointy sticks, which she digs into the ground and props up so that the meat hangs just a few inches above the flames. “We just had a marshmallow roast on this stick,” she says, chuckling.

After the meat has browned and starts to ooze tiny bubbles of white fat, Cynthia cuts off a piece and tastes it. “It’s done,” she says before distributing bite-sized chunks to the visitors and family gathered round, who chat mostly in Cree.

Rabbit camp is both a hunting and gathering place for the Wapachee. While I was there, more than a dozen relatives and visitors cycled through. “We never plan anything, we just bump into each other wherever we go,” says James. “We might even bump into each other in Montreal.” Among the visitors during this trip is Wally Wapachee, one of the elder brothers, with his wife, Linda Bosum, and adopted granddaughter Amberlynn Shecapio, a gap-toothed five-year-old, her hair wild and loose, wearing pink boots and a camouflage sweatshirt about five sizes too big.

“Hey, you wanna’ see her moose call?” asks Wally. “She does a great moose call.” He passes a red horn to the little girl who wails into it. For a pint-sized Homo sapien, she blows a pretty convincing moose.

“Do it again,” says Linda. “I didn’t hear.” Amberlynn does it again, but louder. When hunting is a way of life, kids start early.

Before Wally gets his family back on the road, I ask what he thinks about BlackRock.

“If you follow this road up here,” he says, pointing down Logging Road 210, deeper into the bush, “you can see the whole mountain range that’s going to disappear.” Wally is out-spoken like his father. He believes BlackRock misled the family and the community. According to Wally, the Bally Husky Agreement committed BlackRock to building a work camp that would provide 500 jobs and create many business contracts for the Cree. But the company has walked back the commitment to a work camp and now plans to employ far fewer workers, maybe 150 to 200, and ship most of the ore out by rail. “Canadians call it development,” he says. “We call it disaster.”

At about six in the evening, Wally, Linda and Amberlynn get on the road back to Oujé-Bougoumou. With the sun setting and our appetites sated, Cynthia, John and a few others set out toward Gawashebuggidnajj in two trucks. With John in the lead, we bounce around on bumpy backroads. Every so often, John stops the car and looks out across the swampy shorelines of the lakes for moose feeding in the shallows, as the Wapachee have done for generations. “Don’t be surprised if John stops and shoots a moose,” says Cynthia. During the drive, we pass an old gold shaft, called Le Moine, and then the BlackRock campsite.

As we start to climb Gawashebuggidnajj, I see the birch bark trees for which the Wapachees named the mountain in their mother tongue, clear-cut and stacked two metres high, with the trunks’ round bottoms facing the road. We drive deeper into the bush: 30, 45 minutes, our eyes peeled for wildlife, our wheels skirting axel-breaking potholes every few dozen metres. There isn’t an animal in sight.

But then, as we approach the summit, John spots something moving in the bushes and stops the truck. He fetches his .30-30 rifle, used for big game, and takes aim.

***

Chief Curtis Bosum sits in the stands of the Chibougamau Arena in a Blue Jays cap and zip-up, watching his daughters, Megan, six, Leah, eight, and Leanne, his stepdaughter, also eight, figure skate. Unlike most Cree kids, Curtis grew up middle-class and played hockey at this rink. While relative privilege afforded him the opportunity to skate, it didn’t spare him from racism. Curtis remembers opposing players calling him kawish, a French epithet for Natives, and aits asti Indien, the equivalent of “fucking Indian.” He remembers the prejudice of his friends’ parents. And he remembers how he overcame it: by hanging in there, by having tough and thoughtful conversations. Hockey helped. Curtis learned how to listen to the coach and how to be a team player, which to him meant that despite differences, teammates stuck together on the ice. Curtis remembers how his Quebecois line mates would stand up for him, the only Native in the rink, against all-white teams from Val-d’Or and the Lac Saint-Jean area. “That felt good,” he says.

Curtis’s opportunities reflect the fortitude of his parents. Neither Abel nor Sophie spoke about the abuses they suffered at La Tuque, to spare their children from the ripple effects now well documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Abel, in particular, was a disciplinarian. There were, according to Curtis, rules and regulations: no swearing, no hitting, no wasting food — especially meat. And if you didn’t listen: “there was the belt.”

Like most Cree families, the Bosums hunted together, mostly on the Happyjack trapline near Ramsey Bay. Growing up, Curtis took his little brother Nathaniel under his wing. When Nathaniel was a baby, Curtis changed his diapers. When Nathaniel got older, Curtis hunted and fished with him. And when Nathaniel became a professional motocross rider, Curtis was his manager. When the accident happened, Curtis was the first to get the call. He had to tell the rest of the family Nathaniel was gone. “That was tough,” says Curtis. “I still hear the screams and crying.”

As Curtis tells the story, his son Alexandre, Megan’s twin, comes and sits in his dad’s lap. Alexandre was born without a left eye, a one-in-a-million case, but still plays hockey and other sports. Curtis speaks French to the boy and hands him a credit card to buy poutine. The Bosum household is trilingual, with the kids speaking French, English and a little Cree. For a man who has spent his life navigating the seams between Cree, Québécois and Canadian worlds, this feels appropriate.

In August 2019, Curtis was re-elected Chief for another four-year term. He views his role as Chief not unlike his role as a teammate, brother and father: it’s all about balance. As Chief, Curtis must balance the need to address pressing social issues like education and unemployment with his responsibility to protect and preserve the territory and culture of the nation. This is not always easy. Although he knows development will harm wildlife and the environment, Curtis sees mines like BlackRock as an opportunity to provide jobs and create businesses in a community that needs a lot more of those. He says he has done his best to represent the interests of the Oujé-Bougoumou Cree while giving voice to the Wapachee family’s concerns. He too recognizes the loss the mine will represent. “There won’t be any more mountain,” he says, sitting on the cold metal stands. “Digesting it, it’s a little tough.”

Curtis takes Alexandre down to the locker room to get suited up for practice. The Chief gets his son fully dressed and gives the boy a big, enthusiastic high-five before lacing up his own skates. On the march to the ice, the mites in their Timbits jerseys — mostly boys, but a few girls, too — look like a gaggle of bowlegged astronauts: their pants a bit too long, their helmets a bit too big, their sticks, unwieldy.

At the gate, Alexandre takes off in a circle. Once all the players file out onto the rink, the coaches follow behind, the sound of laughter and little skates scraping the ice fill the arena. A whistle blows, and the kids reverse direction. Another whistle, and they practise skating backward. Curtis approaches a tyke in a red jersey and shows him how to make a C-cut, the fundamental technique for backward movement.

A mama bear stands up on her hind legs in the bushes, sniffing the air. When she spots the trucks, she takes off into the trees, three baby bears following behind. John lowers his gun. The Cree don’t take mothers with cubs. We hop back in the trucks and finish the treacherous drive to the peak of Gawashebuggidnajj, the Wapachees’ traditional moose hunting grounds.

“They say the mountain here is all going to be extracted. There will be no mountain here,” says Cynthia Wapachee, as though she can hardly believe it. She pauses, before adding: “It devastates me knowing that there’s history,” she gestures to the exposed granite mountaintop beneath her feet. She lifts her glasses to wipe the tears welling from her eyes.

She looks out across the land: the forest spotted with silver lakes and streaked with trees turning yellow with the changing season. In the distance is Chibougamau Lake, and just beyond that the sliver of Doré Lake. The Wapachees have traversed this land countless times, stalking antlered giants on the shores of the blue-grey swamps and among the birch trees of the mountain. After a successful hunt, they would return to lakeside homes, a slain beast in tow. From the summit, the distance the Wapachees, their forebears and the Oujé-Bougoumou have travelled appears formidable, but not insurmountable or irreversible. If investors have their way and turn this mountain into little more than a kilometre-long hole in the ground — the titanium, vanadium and iron beneath shipped off to China and wrought into batteries, wind turbines, electric vehicles, implants — maybe then the distance between the past at Doré Lake and the present at Gawashebuggidnajj will be flattened and imperceptible.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?

Science & Tech

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe