Wildlife

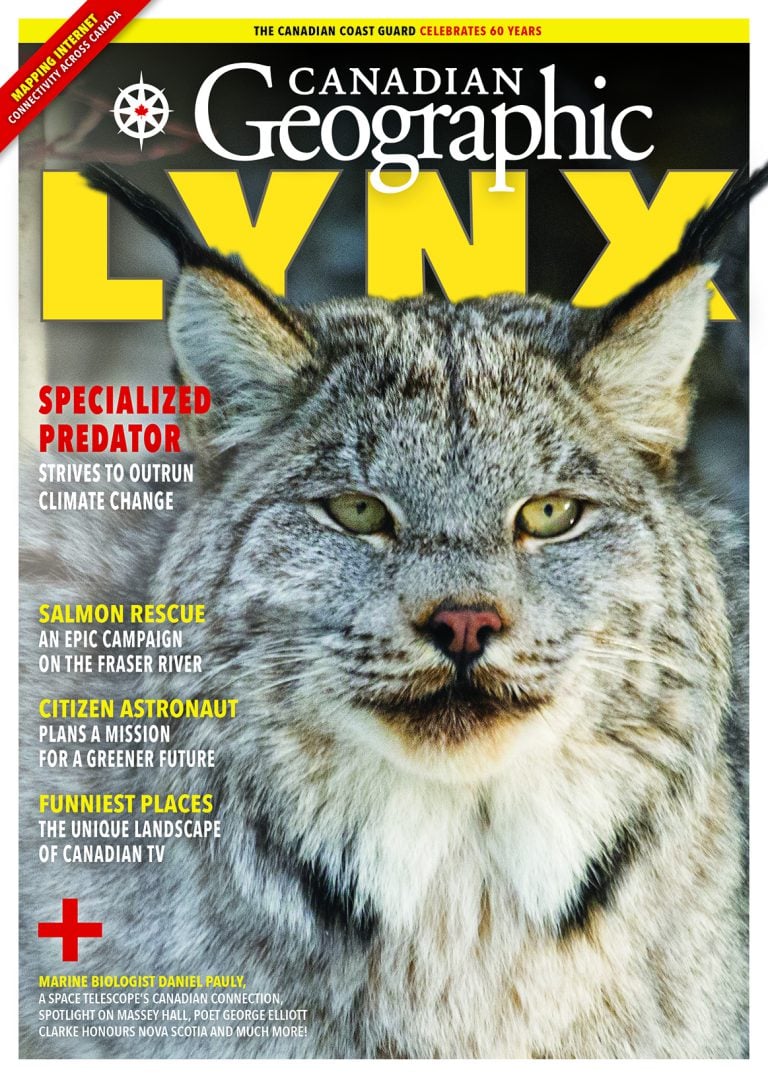

Into the wintry kingdom of the Canada lynx

In the boreal forest, where secretive lynx depend on the snowshoe hare to survive, climate change threatens to upset this longstanding predator-prey relationship

-

Published Jan 10, 2022

-

Updated Jun 16

-

1,160 words

-

5 minutes

-

Photography by Peter Mather

In mid-winter, few predators can match a Canada lynx on the hunt for a snowshoe hare through the boreal forest. They have a competitive edge: wide, padded paws akin to snowshoes that help keep the lynx afloat in deep snow. Where a snowshoe hare might be able to outrun a coyote, leaping lightly across the snow to safety, escape from a lynx is less certain.

Lynx and snowshoe hares have co-evolved to thrive in the snowy, cold and harsh conditions of a northern winter. Alongside large hind feet of their own, snowshoe hares shift from brown to white with the seasons, a trait that lets them hide against the backdrop of their surroundings all year round.

For decades, scientists have been studying the predator-prey dynamic of these two species in the Kluane region of the southwest Yukon, an area within the traditional territories of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations and the Kluane First Nation. There are no pressing concerns about human developments dividing and constricting their habitat in the boreal forest of the Yukon — unlike in some areas of the cat’s southern range. But nowhere is safe from climate change.

What exactly a warming climate will mean for lynx depends in large part on how its primary prey, the snowshoe hare, is affected. The fates of lynx and hares are so tightly entwined that the peaks and valleys of a lynx population mirror, with only a slight delay, the natural boom and bust of snowshoe hares, a population cycle that repeats roughly every 10 years.

While lynx do eat other animals, including red squirrels, snowshoe hares make up most of their diet. When hares are plentiful, lynx may eat once or even twice a day, says Emily Studd, a wildlife ecologist and the lead author of a 2021 study that used audio recorders and accelerometers to track lynx in its Kluane study region. “Imagine what it would sound like if an animal was running full speed through a forest,” Studd says. That’s the sound of a lynx chasing down its prey. A loud crashing, sometimes followed by “the screams of an animal dying,” mark a successful hunt. After, “you can hear the sounds of bones being cracked and broken and chewed,” she says.

This research offers unique insights into the hunting behaviour of the secretive lynx, an animal rarely seen in the wild. “Being a predator is kind of a … rough job,” she says. Meals are unpredictable, and it’s worse when hares are in the natural downswing of their regular population cycle. With fewer hares available, some lynx just can’t survive.

In the future, those recurring busts in the hare population could become more dire for lynx, and the booms less lucrative. Because, as the climate changes, lynx may soon face stiffer competition for their prized prey — particularly from coyotes.

In the forest, lynx have a clear hunting advantage in deep snow that can bog down coyotes. But in shallower snow they lose their edge, according to a Nature Climate Change study published in September 2020. Lead author Michael Peers tracked the fate of 321 snowshoe hares over four winters in the Kluane region as part of his PhD research at the University of Alberta. He found that hares face a significantly higher risk from predators, particularly coyotes, in shallower snow. “It was really clear … that coyotes don’t hunt hares effectively when the snow gets deep,” he says. But deep snow may become less and less of a hurdle for these canine predators. Over the last two decades, maximum snow depth in the Kluane study region has fallen by 33 per cent, the study found. If climate change means a future with longer periods of shallower snow, Peers says, coyotes may kill more hares, adding hunting pressure that may depress the hare population, ultimately dragging down lynx numbers as well.

For now, coyotes typically haunt roadways and communities in the Kluane region, where it’s easier for them to move around in the depths of winter. In Burwash Landing, a small community on the shores of Kluane Lake where Kluane First Nation is based, they’ve become a nuisance. “They’re just pests within the community,” says Kate Ballegooyen, Kluane First Nation’s natural resource manager. They get into people’s yards and garbage and have even gone after some dogs.

Lynx, meanwhile, are highly valued by Kluane First Nation trappers, she says. They have one of the better selling pelts, and the Kluane First Nation government offers an incentive for lynx as part of an overall effort to make trapping more financially viable and to encourage young people to get out on the land. Lynx fur is valued culturally as well. It may be used to line the sides and tops of mukluks and incorporated into other traditional regalia, says Ballegooyen, who has worked for Kluane First Nation for about seven years and also co-authored the journal article “Towards Reconciliation: 10 Calls to Action to Natural Scientists Working in Canada.”

“The fur is beautiful,” she says. But as the climate warms, there could be “dramatic changes in the abundance and distribution of both snowshoe hares and lynx,” says Dennis Murray, Canada research chair in integrative wildlife conservation, bioinformatics and ecological modelling at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont.

While there are still many unanswered questions about the way climate change may affect lynx and hare populations, Murray says the conditions in the lynx’s southern range may offer some insight into their future in the boreal forests of northern Canada. The density of lynx is much lower in their southern range, where they already face considerably more competition from coyotes, foxes, raptors and other generalist predators. Scientists think that may be one reason why the boom-bust population cycles of hare and lynx typical in the boreal forest are less pronounced in parts of southern B.C. and the northwest U.S., says Murray, who is a co-author on both Peers’ and Studd’s papers. “When the hare population crashes in the southern range, those generalist predators can just switch over and start feeding on other things, which keeps their densities at relatively high levels, so that hares basically can’t ever escape being swamped by a bunch of predators on the landscape,” he explains. The hare population never gets a chance to recover.

Murray suspects that’s the dynamic that may eventually — even 100 years from now — play out in the boreal forest. While lynx may adapt by broadening their own eating habits, as they have in their southern range where Murray says they are “less addicted to snowshoe hares,” it may not be enough to keep their population as strong as it is today. “I don’t think we need to be concerned about the extinction of lynx and hares in the core of the boreal forest,” he says. But in the long run, lynx in the Kluane region may be forced to accept the invasion of more new competitors into their wintry kingdom.