People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

You would be hard-pressed to find a more beloved Canadian literary figure alive today than Margaret Atwood. The author of 16 novels, 20 poetry anthologies, numerous works of non-fiction and even an opera, she is also a frequent commentator on Canadian politics and society and a champion of environmental sustainability.

We caught up with Atwood at The Royal Canadian Geographical Society’s 2015 College of Fellows Annual Dinner, where she was keynote speaker and the recipient of a Gold Medal for her innumerable contributions to Canada. There, she shared her thoughts on Canada’s geography, climate change and how to get away with murder in the Arctic.

We understand you’re a huge fan of the Canadian Arctic. How did you become interested in the North?

I grew up in the North on the shores of Lake Superior and, before that, in northern Quebec, north of Temiskaming. We always did a lot of travelling, so I saw a lot of Canada at a very young age. I first went to the Arctic in 1975, and I started travelling in the eastern part of it in 2003. We’ve been going up there quite a lot ever since. It’s a stunning part of the world. You’ll never think about the planet in the same way again once you’ve been there.

Is that what first made you aware of climate change?

My parents were early environmentalists in the 1940s, when everybody thought it was a bit crazy or eccentric. My dad was a biologist and he saw climate change coming for a long time. My mother actually saved a report from The Club of Rome in 1972 that predicted everything that’s been happening. So that is something I grew up with, and I’ve noticed it with alarm ever since.

Have you seen evidence of climate change on your trips to the Arctic?

Absolutely, and so has everybody who goes there. It’s not just some eccentricity of mine. The good news is that people are finally noticing it and seem to have some sort of will to act. The number of deniers are shrinking.

How has your love of the Arctic influenced your writing?

In my collection of stories called The Stone Mattress, there is a story I actually wrote in the Arctic that answers the question we all think when we’re on a boat up there: how do you murder somebody on a boat in the Arctic and get away with it?

Wait — does that question really occur to everyone who travels there?

[Laughs] It comes to everyone sooner or later: how would I murder somebody on this boat? It was actually Graeme Gibson who came up with the basic elements of the plot. He had it figured out, so I then wrote the story. It features an energetic young geologist, [RCGS Fellow] Marc St.-Onge. His reaction to being in the story was not “Hurray, I’m in a story,” it was, “Oh Margaret, it’s so wonderful that geology is in a work of fiction.” In the story, the murder weapon is a stromatolite, which is a 1.9 billion-year-old fossil of the lifeform that created the oxygen that we’re breathing right now. There’s a great big field of them in the Arctic and they would make dandy murder weapons.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

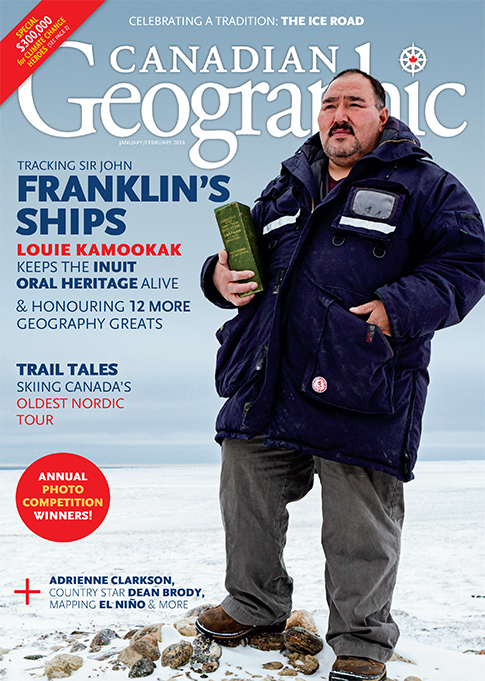

This story is from the January/February 2016 Issue

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

The director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reflects on Indigenous progress in 2017 and looks ahead to 2067

People & Culture

For unhoused residents and those who help them, the pandemic was another wave in a rising tide of challenges

Wildlife

How ‘maas ol, the spirit bear, connects us to the last glacial maximum of the Pacific Northwest