Science & Tech

20 Canadian innovations you should know about

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

- 3327 words

- 14 minutes

History

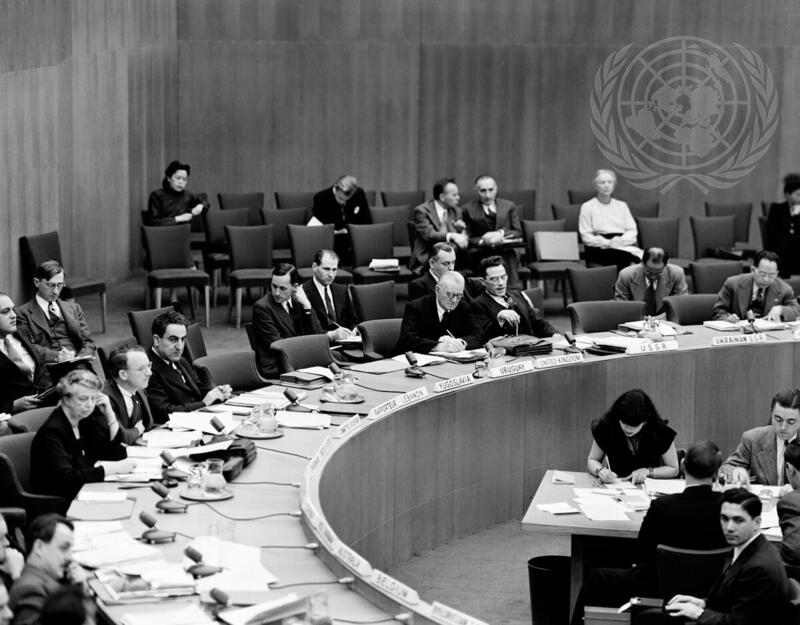

On Dec. 10, 1948, the United Nations adopted an aspirational document articulating the foundations for human rights and dignity, but who was the Canadian that helped make it possible?

This feature forms part of Commemorate Canada, a Canadian Heritage program to highlight significant Canadian anniversaries. It gives Canadian Geographic a chance to look at these points of history with a sometimes celebratory, sometimes critical eye.

John Humphrey had once been a child who had played with fire.

He had been burned — his left arm amputated as a result.

Born in Hampton, N.B., in 1905, Humphreys lost both his parents to cancer by age 11. Tragedy would follow him into his school years, too, where he became the victim of bullying.

“It’s a matter of psychological speculation to connect his early experiences with his adult accomplishments,” explains Dr. Clint Curle, author of Humanité: John Humphrey’s Alternative Account of Human Rights. “Nevertheless, I suspect he would be quite strongly opposed to the suggestion that the human rights project was, and is, somehow anchored to his own personal background.”

One thing remains clear: For much of his life, John Humphrey would dedicate himself to enshrining the rights of humankind in international law, the standards of which would transcend all political and societal ideologies.

His contributions, most famously through a shared role in drafting the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), would prove an uphill struggle in many ways. Nor has the UDHR always lived up to its aspirations in the years and decades since. But it was a good beginning.

For Humphrey, the journey had begun in the 1920s when he enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, graduating with a Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1925, a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1927, and a Bachelor of Law degree in 1929.

He was subsequently awarded a fellowship to study in Paris, France. En route, Humphrey met his soon-to-be wife, Jeanne Godreau, marrying her shortly after arriving in France. It was likewise abroad that he reportedly solidified his passion for international law.

Humphrey’s advanced studies continued back in Canada and, in 1937, he took on a teaching position at his old university. There, in the early 1940s, he met Henri Laugier, a refugee from France operating with the Free French, a resistance movement that came together in the aftermath of the Nazi invasion of continental Europe. Their working relationship and mutual respect would one day have a considerable influence on creating the UDHR.

At that time, however, such aspirations seemed distant amid a calamitous war.

“In the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” notes Dr. Jeremy Maron of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, “it talks about the atrocities of the Second World War. It calls them ‘barbarous acts’ that outraged the conscience of humankind, making it very clear the need for an international standard of human rights and conceptions of human dignity.

“Of course, these conceptions did not suddenly emerge between 1945 and 1948. They’ve been talked about in different ways by a variety of different cultures at different points in history … But it was really the horrors of the war, including the Holocaust … that were the impetus for drafting the UDHR.”

The potential for that draft had indeed gained traction by 1946 when Henri Laugier — now the assistant secretary-general to the United Nations — approached his old friend John Humphrey about a new position: the first director of the United Nations Human Rights Division.

Humphrey accepted the role and was eventually tasked with writing the very first draft of the UDHR. Yet he was not strictly alone in his remarkable efforts.

“According to Humphrey, there was an inner circle of folks working together to bring the declaration to life,” says Dr. Curle. “They were [Former U.S. First Lady, U.N. Human Rights Commission Chairperson, and U.S. representative] Eleanor Roosevelt … [French representative] Rene Cassin … [Lebanese representative] Charles Malik … and [Chinese representative] P.C. Chang. Many others were involved in the broader circle, but this small group, including Humphrey, was really in lockstep throughout the drafting process.”

The UDHR today stands as a testament to their joint achievement. Through various drafts and readings, the commission created a globally recognized document that lays out the foundations for human rights and dignity.

There were many hurdles along the way. Among the issues was the preponderance of wealthy Western nations that comprised the United Nations membership (fewer countries from other parts of the world belonged to the organization during the late 1940s). Not everyone, in other words, had a seat at the table. But even with this more limited membership, finding a compromise proved to be a herculean task for the U.N. Human Rights Commission.

“At one of the votes at the General Assembly, Canada abstained,” notes Dr. Curle. “The Canadian Bar Association was lobbying the federal government to not sign it because they thought that some of the provisions were of a communist nature … Of course, John Humphrey hit the roof.”

Ultimately, after walking a fine line between accommodating nation-states and maintaining the declaration’s goals, the UDHR was adopted at the United Nations General Assembly held in Paris on Dec. 10, 1948. Within the ratified document were the inalienable rights of all human beings, regardless of race, colour, religious beliefs, sex, language, and other essential considerations.

John Humphrey, alongside all the drafters, had achieved an extraordinary feat in creating the UDHR that had then been accepted on the world’s stage.

A good beginning it was — but a beginning, nonetheless.

“The UDHR was conceived as part of a broader International Bill of Human Rights that would include legally binding covenants,” says Dr. Maron. “The UDHR is thus not a legally binding document; it’s an aspirational document … the delay [in adopting the International Bill of Rights] was the fact that these covenants would have legally enforceable mechanisms that the signatory countries would have to respond to in terms of regularly reporting on their adherence to civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights.”

It wasn’t until 1966 that the United Nations transformed the ideals of the UDHR into law by passing the International Bill of Human Rights, including its vital covenants. That same year, after two decades of service, John Humphrey retired from the U.N. to resume his McGill University teaching career, although he remained active in promoting human rights until his death in 1995, aged 89.

Humphrey’s later work extended to representing Korean comfort women — enslaved for sex by Japanese soldiers in the Second World War — and former Canadian prisoners of war who had suffered abuses in Japanese POW camps. He also helped found Amnesty International Canada and investigated human rights violations in the Philippines under dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

But perhaps his greatest legacy was, and remains, his role in drafting the UDHR.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

People & Culture

The Charter goals and Indigenous people living in Canada

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Wildlife

Canada jays thrive in the cold. The life’s work of one biologist gives us clues as to how they’ll fare in a hotter world.