Exploration

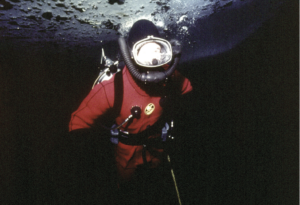

King of chill: Diving in the Arctic with the future King Charles III

Remembering a 1975 journey under the ice of the Northwest Passage with King Charles III

- 2808 words

- 12 minutes

Travel

Robin Esrock heads to Whistler to tick the world’s fastest sliding track off his Canadian bucket list with a special appearance from Olympic champion Jon Montgomery

I’m bulleting down the world’s fastest sliding track, trying to catch a thought. Since my breath is somewhere back at the launch, I’m doing my best to take it all in, clocking 94 kilometres per hour, laying on my stomach, head first, eye mere inches from the ice.

A few minutes ago, at an orientation for the only public skeleton ride in Canada, the instructor advised me to lie down like a sack of potatoes and simply enjoy the ride. A sack of potatoes would better reflect on the experience because the skeleton is too fast, too scary, and too damn insane for the human brain to register. I do recall a fleeting moment where I cursed Prince Harry, but more on that later.

The skeleton is a sport that requires individual athletes to hurtle themselves down an ice track at speeds of up to 145 km/hr. It evolved from tobogganing in Switzerland and actually predates its sliding companions, the bobsleigh and luge. While skeleton sounds morbidly dangerous, the name of the sport has nothing to do with the risks involved. When a simple wooden sled evolved into a metal slab with long handles and a ribbed frame, proponents thought it looked like a skeleton, and the name stuck. Although the sport debuted at the Winter Olympics in 1928, it went on a long hiatus and only became a permanent fixture for both men and women at the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City.

Much like the modern luge, the first sliders went feet first, but faster times were recorded going headfirst. In a race against both the clock and competitors, milliseconds matter. Just ask Jon Montgomery, who took skeleton gold for Canada at the Whistler Olympics in 2010, celebrating with a well-deserved pitcher of beer. Today, he’s better known as the host of Amazing Race Canada. I asked him why anyone would sign up for the skeleton in the first place.

“If you want to experience the thrill of opening your car door while driving down the highway, placing your face millimetres from the surface of the road, and then taking the off-ramp at full speed, I’d suggest you try skeleton racing instead of imminent death,” Montgomery tells me. Skeleton racing clearly attracts a very special kind of competitor, and having a good sense of humour probably helps. But why didn’t Montgomery choose the luge or bobsleigh instead?

“I chose skeleton racing because I’d have to either eat lead weights or grow a massive goitre to be heavy enough to compete in bobsleigh, and I always looked at luge like trying to bring your Christmas tree into your house, tip first,” he says.

It’s Sunday afternoon, and I’ve joined a group of 18 excited and understandably apprehensive public sliders at the Whistler Sliding Centre. We learn about the track, the sport, and gear, and most importantly, the technique. This primarily consists of lying down on the sled, slightly raising our heads, keeping our shoulders in, arms straight, and shoes off the ice. Should we fall in love with the speed and thrill, we’re encouraged to learn more about B.C.’s Sliding Development program. After all, each public skeleton is the first step on a journey that could end on an Olympic podium.

To master their craft, skeleton competitors need frequent access to one of the world’s 16 competitive sliding tracks, just like Montgomery had growing up in Calgary. Built for the 1988 Winter Olympics, Calgary’s track permanently closed in 2019, leaving Whistler as the only Canadian ice track in operation. While athletes from Canada and around the world train in Whistler, I ask Montgomery if a scarcity of tracks might deter future champions.

“If someone is desperate enough to become an Olympic athlete and daft enough to think sliding down a frozen toilet chute and speeds over 145 km/hr seems like a good time, geography will not stand in their way,” he replies. Fair enough.

For safety reasons, the public skeleton only covers the lower two-fifths of the track. This is, after all, the fastest track in the world, one in which a Georgian luge competitor tragically lost his life at the 2010 Olympics. Public sliders won’t be reaching nearly the same speeds or g-force as professional athletes, and the track was modified after the accident. While other tracks around the world offer a public skeleton, sliding in Whistler comes with additional bragging rights.

“In the interest of athlete safety, the upper threshold of achievable speeds has been realized in the construction of the 2010 Olympic track in Whistler,” explains Montogomery. “The track is the fastest in the world and the fastest track that will ever be built. Win Canada!”

Our group is instructed further on how to become “one with the sled,” advised to stay calm and breathe, and most importantly, to not let go of the sled in the unlikely event we fall off it. Launching from the tourist push-off start, all we have to do is navigate six wild turns, and by navigate, I mean hold tight and pray. We walk up to the launch, receive our race order, and listen to the announcements. Individual speeds and times will be clocked, and our descent will be over in less than 36 seconds. This is why everyone gets two runs: the first to get over the fear, the second to correct one’s form and make this an actual race. Nerves clanged with the yellow promotional Invictus cowbells fastened to the gates. My visored helmet did add an element of comfort, along with the reassurances of our friendly instructor, a retired Canadian Olympic bobsledder. The whole operation is as slickly run as the ice, with on-site medics on standby just in case something happens, the likes of which I don’t want to contemplate.

The track announcer gives the all clear, I’m pushed off, and I immediately think, hey, this isn’t so bad. Then the chute drops, speed explodes, and I can’t think much of anything. I see ice, hear the scrape of ice, and feel the acceleration in my bones as the sled snaps up the curving walls before straightening out in the chute. Moments later, I shoot through a corner and up the slope across the finish line, where the sliding team congratulates me for not ping-ponging off the walls, assisting my wobbly legs off the track. It’s at this exact spot where Prince Harry promoted the 2025 Invictus Games – the international sporting event he founded for wounded, injured or sick personnel and veterans – with a media circus to capture his own successful public skeleton experience. Like many others, his little stunt inspired me to give it a go, too.

On my second run, I clocked 93.6 km/hr with a finish time of 34.55 seconds, placing me in a disappointingly 13th position for the race. According to the provided score sheet, a chap named Mathieu hit 98 km/hr and finished in 33.05 seconds. I expect the Canadian Olympic Skeleton Team might want a word with him. Just 2.3 seconds separated the fastest participant from the slowest. Prince Harry reportedly hit an impressive 99 km/hr. It should be noted he has a lot of experience quickly sliding away from the paparazzi.

“Everyone should do this. It should be compulsory!” the elated Prince told the media after his second run, adrenaline no doubt sliding down his veins. Montgomery reckons Prince Harry should try it at the top next time, but the rest of us should stick to the tourist start for the “thrill of a lifetime.”

After my own two runs, I recommend the skeleton to those with a sense of adventure, a curiosity for winter sport, and Whistler visitors in search of a wild, rare, and blisteringly fast bucket list experience.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

Remembering a 1975 journey under the ice of the Northwest Passage with King Charles III

Exploration

Souvenir d’un périple sous la glace lors de la venue du roi Charles III dans le passage du Nord-Ouest en 1975

People & Culture

An exclusive Q&A with British explorer, comedian and actor Michael Palin

Travel

Jill Doucette, founder and CEO of Synergy Enterprises, shares insights on new trends in the tourism industry and why there’s reason to be optimistic about a sustainable future for travel