Environment

The sixth extinction

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

- 4895 words

- 20 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Wildlife

Conserving at-risk species is difficult when they’re constantly crossing international borders, but digital tools are making it easier than ever to track feathered globetrotters

The quiet Canadian winter is beginning to burst forth into the colourful symphony of spring. Every year, millions of songbirds fly thousands of kilometres from their southern wintering grounds to breed in Canada. Among them is my favourite: the tiny Canada warbler, which to me is like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, but in our forests.

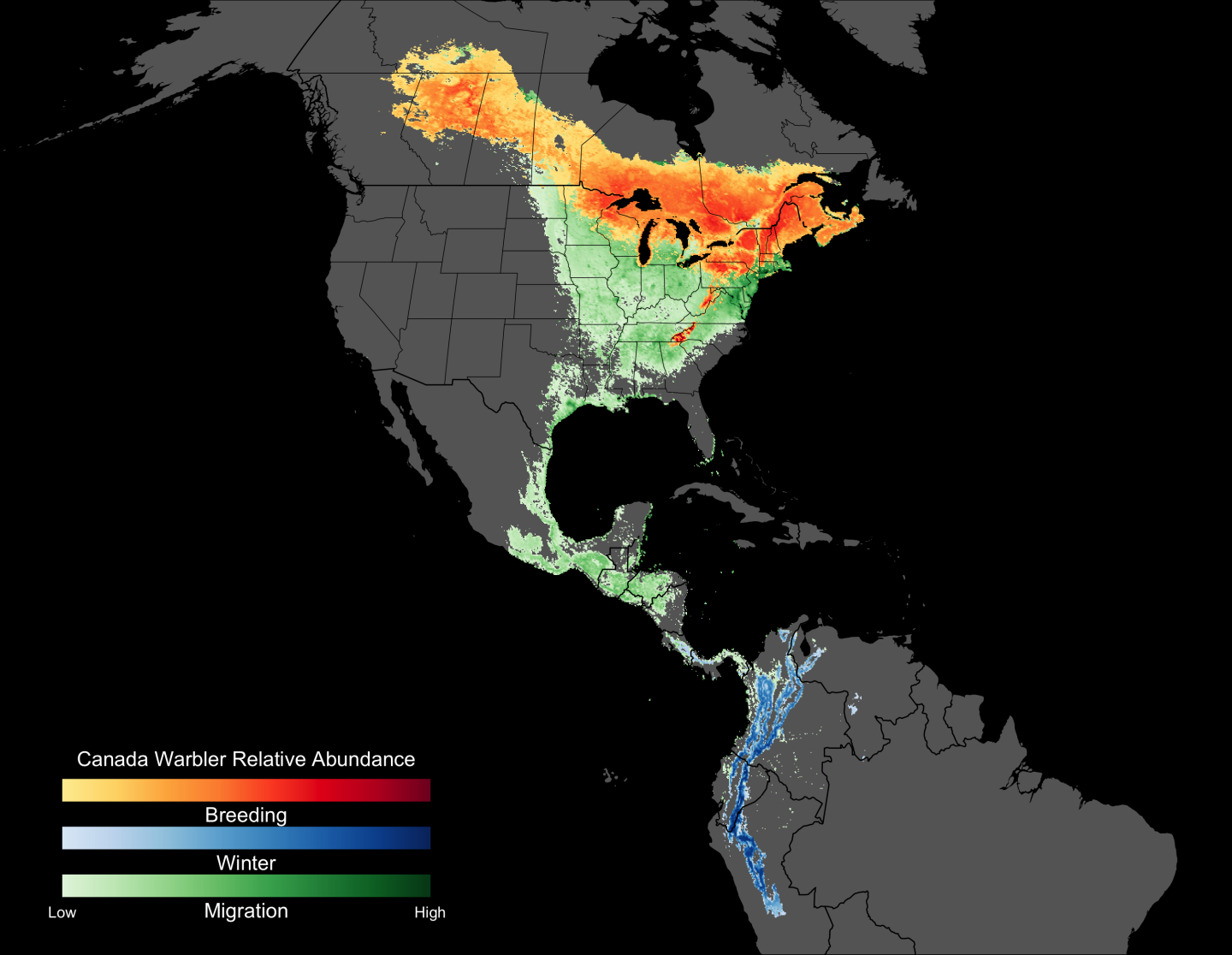

Weighing only as much as a AAA battery, the Canada warbler flies more than 5,500 kilometres from its winter home in South America to mate and nest in Canada. Canada warblers migrate at night and it’s possible for them to make their incredible annual journey up to eight times throughout their lives.

Unfortunately, like many Canadian songbirds, the Canada warbler is at risk of extinction. It’s legally listed as Threatened in Canada and as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in nearly every U.S. state that it visits. The main reason for the Canada warbler’s decline is thought to be human disturbance of mature forests in both Canada and South America. Without prompt and effective conservation efforts, the fate of the Canada warbler is almost sealed.

Many other birds are in trouble for similar reasons. It’s estimated that today, there are 1.5 billion fewer songbirds than there were in 1970. Of the 1,154 North American bird species, 426 of which spend at least part of their time in Canada, one third need urgent conservation action. We have to figure out how to better protect migratory birds.

Birds encounter many threats throughout the year, including storms, predation from domestic cats, collisions with communication towers and buildings, pollutants, and more. One of their biggest challenges is simply finding habitat that provides enough food and shelter to survive and raise young. This problem is magnified because they migrate over such large distances: migratory birds need different habitat in the summer, winter, and during spring and fall migration. Some bird species need to eat every day during migration. Other birds, like the blackpoll warbler, almost double their body weight before flying 3,700 kilometres non-stop from Canada to northern South America—a journey that takes around 86 hours. Scientists like me now look beyond those species’ Canadian breeding habitat to see where else conservation may be required.

It’s a complicated problem. Hundreds of migratory bird species arrive in Canada each spring. They come from all over the world, including Mexico, Bolivia and Argentina. Many of them are endangered in Canada. How can researchers collect enough information about migratory birds to effectively plan continental-scale conservation? And how can we do it quickly enough to help species that are at risk right now? Not only are songbird numbers declining and their ranges constricting; conservation funding and human resources are also limited. Plans are urgently needed that maximize the efficiency of financial investments and on-the-ground action.

Identifying cost-effective habitat conservation for migratory birds is exactly what my research partners and I study. We use the largest biodiversity-related “citizen science” project in the world.

It all started with a simple idea: there are millions of individual birdwatchers across the world, each with unique knowledge and experience. They make exactly the kind of observations that researchers need to understand where migratory songbirds live and move. But without a way to harness all their observations, the information can’t be used to study or conserve birds. There needed to be a simple, free way for birders to collect, archive, and publicly share the information they were collecting.

Enter “eBird,” developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birders download a free mobile app onto their smartphone or tablet. They enter information about the birds they observe from anywhere around the world – even offline. For example, Caroline a birder might go to High Park in Toronto in May and hear a Canada warbler. That birder can immediately take out their phone, open the eBird app and submit the data. They can also see what other birders are reporting locally and beyond, explore birding hotspots, and search photos and sound clips to help them identify birds in the field.

eBird is very popular: more than 100 million bird sightings are contributed each year from ‘eBirders’ around the world, and more than half a billion sightings have been entered in the 15 years since eBird was created. This is the kind of data that scientists like me dream about. Without citizen scientists, we couldn’t collect that amount of information in a lifetime.

How do these data help the tiny Canada warbler on its transcontinental migration? I work with scientists from the Canadian government, Carleton University, the University of British Columbia, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Together, we combine eBird data from more than 100 songbird species that migrate from Central or South America to Canada and the U.S. We specialize in using statistical models and spatial mapping to analyze data entered in the field by eBirders.

eBird data enable us to accurately predict where species are each week of the year. This allows us to identify which places on the birds’ migration paths might be most critical to their survival. That in turn tells us where to focus conservation efforts.

Of course, when dealing with hundreds of unique migratory songbird species across thousands of kilometres, things can get quite complex, quite quickly. We study where the most species are during spring migration, at their summer breeding locations, during fall migration and again at their winter locations. Sometimes we might need to know information at very local levels. For instance, which weeks of the year do flocks of migrating birds land on rice fields in the Central Valley in California? At other times, we might examine patterns of species abundance across continent-spanning flyways. It wasn’t possible to track bird movements throughout the year before modern computing power and without the vast datasets from eBird. These advances allow researchers to explore creative and effective conservation solutions.

One such creative solution is the Bird Returns program in the Central Valley in California. The program, financed by The Nature Conservancy, pays rice farmers in the birds’ flight path to keep their fields flooded with irrigation water from the Sacramento River as migrating flocks arrive. The prices are determined by reverse auction, in which farmers bid for leases and the lowest bidder wins. Fields that were enrolled in the program showed three times greater species richness and five times higher bird densities than unenrolled fields. This clearly shows a benefit to migratory birds in this important flight path.

We recently examined plans to conserve migratory birds of the western hemisphere over their annual journey. We were excited to find high compatibility between those plans and land use likely to support human livelihoods, such as maintaining small scale agricultural areas. This indicates that incentives to avoid agricultural intensification may be required to ensure that these efficiencies are retained. The high concentration of migratory birds and land required to support them in the winter period further emphasizes that investments in South America and the Caribbean currently represent the most efficient way to conserve many of these species.

People have known for a long time that protecting and conserving habitat is critically important for the long-term survival of migratory birds like the Canada warbler. eBird and more than 300,000 eBirders around the world make it possible for researchers like me to consider the full annual journey of migratory birds—information that can translate to better conservation. With the help of current and future eBirders, we are hopeful that we will be able to make informed and cost-effective decisions to protect the Canada warbler and other feathered globetrotters.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Wildlife

An estimated annual $175-billion business, the illegal trade in wildlife is the world’s fourth-largest criminal enterprise. It stands to radically alter the animal kingdom.

People & Culture

Naming leads to knowing, which leads to understanding. Residents of a small British Columbia island take to the forests and beaches to connect with their nonhuman neighbours

Environment

Indigenous conservationists are listening in to track the impacts of climate change on the boreal forest