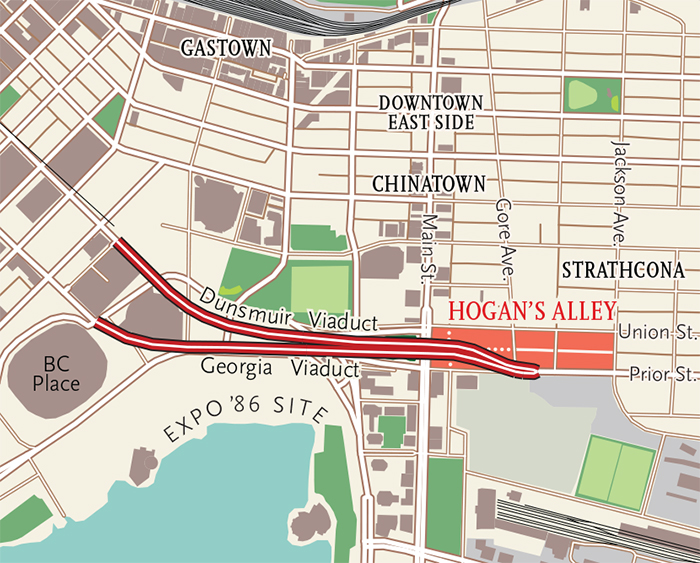

Map: Chris Brackley/Canadian Geographic. Map data © Openstreetmap Contributors

According to local lore, the shrine was once the kitchen of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, where Hendrix’s grandmother worked, and where the guitarist spent some of his childhood summers. It’s also one of the few remaining buildings that were once part of Hogan’s Alley, Vancouver’s first and only predominantly black neighbourhood. The district’s few blocks were razed in the early 1970s to make way for the viaduct.

The alley was known for gambling, brothels and bootlegger bars. It was also a place where black musicians such as Louis Armstrong went when they were in town, to play music and eat at one of the alley’s famous chicken shacks.

But Hogan’s Alley began to change in the 1960s as plans emerged for an urban freeway that would cut through the area. “It became a different neighbourhood, a rundown neighbourhood,” says Randy Clark, whose family’s home was expropriated to make way for the development.

The viaduct was the first phase of the freeway, which was meant to extend through East Vancouver, but community protests halted the project before it got past Hogan’s Alley. Condominiums have since sprung up in place of the few row houses that survived.

The city lost a unique melting pot, says Clark. “Italians grew up with Japanese who grew up with blacks, and everybody seemed to get along. Some of that changed with the freeway.”

A plaque now commemorates Hogan’s Alley, and city council is moving ahead with plans to tear down the viaduct, which doesn’t operate to capacity, is expensive to maintain and acts as a barrier between neighbourhoods.

For Wayde Compton, co-founder of the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project, removing the viaduct won’t bring back the former community — nor should it. “It’s a different neighbourhood today,” he says, “and it belongs to the people who live there now.”